Digital Indians: Ben Gomes

- Published

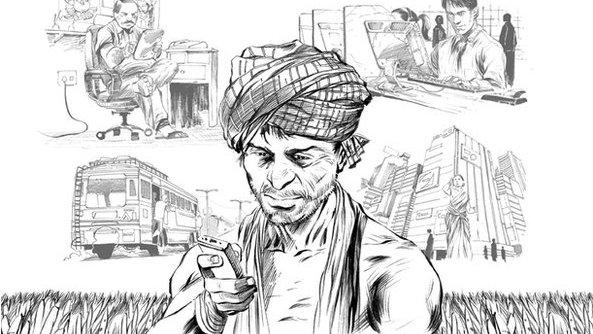

Ben Gomes' first love was chemistry. (Illustration: Sumit Kumar)

What do you do if you get more than three billion queries a day?

If you are Ben Gomes, Google's Tanzania-born, India-bred, US-educated vice-president of search, you are responsible for helping to answer all of them - in the shortest time possible, on all devices: desktops, tablets, phones. And now, in the spoken word too.

Search, external is Google's raison d'etre and cash cow, bringing in a bulk of its $50bn (£33bn) revenues last year. It is also, says Mr Gomes, "about having a continuous conversation with the user to find out what he wants".

For a change, we are having a conversation with Mr Gomes, the boy-like 45-year-old guru of search in Googleplex, the funky low-slung company headquarters set in the manicured greens of Mountain View, California.

Mr Gomes works out of an untidy cubicle with four other top engineers in Building 43, the Mecca of search. There are papers strewn around, a headphone lies idly on his table and numbers are scribbled on a whiteboard.

Wrapped around the thin walls near his standing workstation are posters of Russian abstract artist Wassily Kandinsky's work.

From his modest lair, Mr Gomes and his team work relentlessly on their fine-tooth comb search of the worldwide web to serve up the popular search engine, which is now a part of our everyday lives.

"When I joined Google in 1999, search was about basically finding the words that you search for in a document. Then we took this view that we were going to understand what you want and give you what you need," he says.

Today, crawling through more than 20 billion pages a day on the continuously expanding world wide web, Mr Gomes and his army of search - a substantial number of the company's 44,000 employees - use algorithms in an attempt to make search intuitive, multimedia and super smart.

The "maths that computers use to decide stuff" - as algorithm expert Kevin Slavin called it once - helps rank pages in order of their importance, identifies spelling errors, provides alternatives to words, predicting auto-complete queries, and does unified searches using images, audio and video and voice.

They also try to delve into the deeper meaning of words searched for - "less 'searchese' and more natural language", as one employee tells me - and recognises words with similar meanings.

Ben Gomes, Google's vice-president of search

And then, with a hint of understated pride, Mr Gomes talks animatedly about Knowledge Graph, external, a new function launched last year to make the site's algorithms "act more human" in an attempt to offer instant answers to search questions. Time magazine called it the "next frontier for search".

"It's a database of all things in the world. It pulls together different databases and unifies them into a single coherent one that has about 500 to 600 million people, places and things in them and about 18 billion attributes and connections between those things," he says.

But some sceptics like independent technology columnist Mala Bhargava believe there are some pitfalls.

"Google does a great job of evolving search continuously, slipping in new features all the time. But innovation always walks a tightrope between being useful, even prescient, and being so excessively personalised and targeted as to be meaningless," she says.

But folks at Google believe the fact that it handles a mind-boggling 100-billion plus searches every month, or over three billion a day is testimony to its popularity. A good 15% of the search questions it sees every day are new - queries it has never answered before.

Then there's the giddy speed of search.

When Mr Gomes joined Google in 1999 after a stint in Sun Microsystems working on Java programming language, some searches could take up to 20 seconds. When I keyed in Ben Gomes on Google recently it spat out 19,000,000 results in .28 seconds. (Most of the top ranked results were about the search guru himself.)

Chemical interest

What the search on Mr Gomes possibly will not tell you is that as a young boy growing up in Bangalore, he was more fascinated with chemistry than computers in the beginning.

The future of search is on mobile devices, says Mr Gomes

So much so, he recounts, that one day he picked up some sulphuric acid from a city shop, and walked into his school, "swinging the bottle in my hand, so happy".

But then he went to a school with classmates like Krishna Bharat, a computer fiend who later become the man behind Google news, and which counted Sabeer Bhatia, founder of Hotmail, among its students.

So when his brother bought him a small microcomputer in 1983, young Ben joined a small bunch of people interested in machines in what then still was a technophobic country.

Mr Gomes, son of a car distributor father and a school teacher mother, moved to the US 25 years ago. He went to Berkeley, where he picked up a PhD in computer science.

And then the internet happened.

It was about that time his classmate Krishna Bharat told Mr Gomes about Google, and he joined this relatively unknown company "because it would make this content available to the world through a really good search".

The rest is search history.

Presidential search

What is the next frontier of search, I ask Mr Gomes, before heading for a meal at the Indian curry station at Googleplex.

"Now search is becoming mobile - on phones and tablets. The challenge is that it is on a small screen, so it's hard to type. The opportunity is that it's got a really good microphone and a touch screen.

"It can enable a new kind of interface. So we realised we want to build an interface that was much like the way you talk to some person and ask a question," he says.

And then, with a gleam in his eyes, Mr Gomes picks up his HTC smartphone and barks a series of questions into the Google search app.

"Who is the president of India?" he asks.

"Pranab Mukherjee," promptly answers a woman's voice.

"How old is he?" Mr Gomes prods on.

"He is 77 years old," she answers, loud and clear.

"This is cool isn't it?" says Mr Gomes.

"And it's going to get better and more intelligent."

- Published3 September 2013

- Published2 September 2013

.jpg)

- Published10 September 2013

- Published19 March 2013

- Published25 April 2013

- Published24 June 2013

- Published10 March

- Published18 July 2013