Robo-mate exoskeleton under development in Europe

- Published

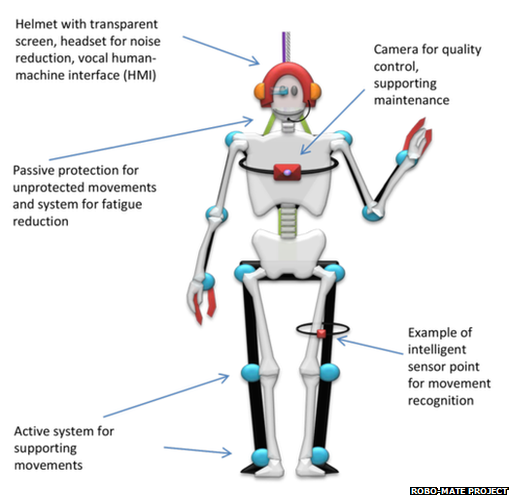

The exoskeleton aims to make it safer for staff to handle heavy weights

Efforts to develop an exoskeleton for the workplace are under way, backed by EU funds.

Twelve research institutions from seven European countries are involved in the Robo-mate project, which hopes to test a robotic suit that can be worn by factory employees within three years.

They say the machine could reduce the number of work-related injuries.

One expert warned employers would need to be convinced the equipment would not pose safety issues of its own.

Manufacturers including Italian carmaker Fiat and the French vehicle recycler Indra are working with the teams.

The companies will suggest situations in which the tech could prove useful and have also said they would help test it.

The EU has committed 4.5m euros (£6m; £3.8m) to the scheme.

Heavy weights

The project aims to address the fact that many manufacturing tasks are difficult to automate.

For example Indra has to deconstruct many different types of car, and at present humans, rather than robots, are the only ones capable of handling the complexity of the choices involved.

Because of the weights involved, this can put staff at risk of developing medical problems.

"People have to manipulate parts or components that weigh more than 10kg [22lb]," said Dr Carmen Constantinescu, from Germany's Fraunhofer Institute, one of the organisations involved.

"These activities are not carried out just once per day, but are repetitive.

"An exoskeleton with a human inside represents a new type of research for the manufacturing industry.

"It offers a hybrid approach in which the robotic parts support the human who can provide the decisions and cognition needed."

The partners have highlighted a study by the UK's Work Foundation think tank that suggested as many as 44 million people in the EU have suffered work-related musculoskeletal disorders.

The US Army has tested the use of an exoskeleton to help its soldiers run while carrying heavy gear

Not all would be preventable by such an exoskeleton, and one of the other researchers involved said part of the challenge would be indentifying where the tech could prove useful.

"One area would be, is it useful to lift heavy loads?" Prof Darwin Caldwell, from King's College London, told the BBC.

"The other is situations when people are working above their head.

"If you hold a paint brush or a screwdriver above your head for more than two to three minutes your arms become very fatigued and it can be very bad for your heart."

However, he said the engineering teams were mindful of the risks involved.

"At the minute the motors or hydraulic systems required tend to be rather large and clumsy," Prof Caldwell said. "What we have to do is find ways to miniaturise those.

"What we also have to remember is that an exoskeleton is essentially a robot in physical contact with a human.

"That raises safety issues so we will be looking at making the interaction between the two softer and more organic - it won't be like having a large industrial robot which is dangerous."

The researchers have already suggested some of the technologies they plan to include

One roboticist who is not involved in the project said he expected such technology to become commonplace within the next two to three decades.

"A number of exoskeletons have been developed for military use in the US, and for helping the disabled and frail older people to walk again in Japan - industrial use is an obvious next step," said Prof Noel Sharkey, from the University of Sheffield.

"But one hard problem is how the human user interfaces with the device. It is vital that the operator can perform dextrously with natural movements without having to think about it.

"Another problem is how to work in environments with other humans without hurting them. This will require new natural collision avoidance methods."

- Published2 August 2013

- Published25 April 2012