Where is the next generation of coders?

- Published

A robot controlled by a tablet, which can turn its head 360 degrees, has been developed

These days coders are as in demand as supermodels were in the 1980s.

From banks to hospitals to local government, everyone wants a techie on their team.

But just as more and more jobs rely on computing and coding, so conversely fewer people have the skills to fill them.

To head off a global coding crisis, something needs to be done to persuade youngsters that there is more to coding than dark rooms, pizzas and unsociable hours.

Robot friends

For Vikas Gupta, former head of consumer payments at Google, the answer lies in starting them early.

"I have a daughter aged two and I wanted to do something for children. I started to wonder at what age children can grasp coding concepts," he told the BBC.

Children as young a five are able to grasp coding concepts as long as the learning is done through tangible interactions, according to an MIT study that Mr Gupta came across.

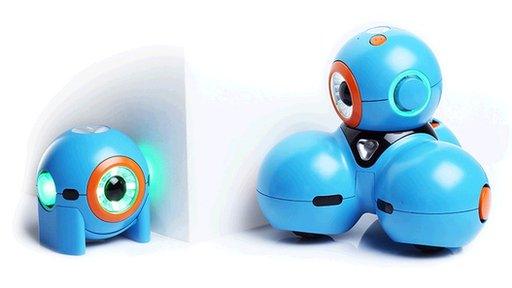

Can Bo and Yana inspire young children to code?

"That was eye-opening for me. And there were no products that exist for that age. So I set out to design something that a child younger than 10 can have fun with and learn programming," he said.

He came up with Bo and Yana, two robots that aim to teach children about programming without them even realising it.

Yana is the smaller robot and can be programmed to make sounds and perform actions.

Bo can be programmed to move around and the robots interact with each other.

"They can be programmed to play hide-and-seek," said Mr Gupta.

Initially children just start by playing a variety of games with the robot, barely aware that they are coding.

Once they have got the hang of that, they can move on to use visual programs such as Scratch to create their own code.

Both robots are controlled wirelessly via a tablet or smartphone - currently the app is only available for iOS devices.

The project is crowdfunded and hit its $250,000 target within three days.

The plan is to start selling the robots in the summer of next year.

Mr Gupta is also keen to get the robots into schools and is working to develop curriculum resources for them.

Tech education

As part of his research, Mr Gupta was shocked at the state of technology education in the US.

"Computer science education has got worse in the last 20 years rather than better," he said.

A 2010 report from the Computer Science Teachers Association seems to bear this out.

It found that more than two-thirds of US states had little or no computer science standards at secondary school level.

There was also "deep and widespread confusion" about what technology education should consist of, whether it be computer literacy or computer science.

The report concluded that the US had "fallen woefully behind in preparing students with the fundamental computer science knowledge and skills they need for future success".

Coding from day one

Children are used to using technology before they go to school

It could draw some valuable lessons from Estonia.

The Eastern European country may only be small - its population is just 1.3 million - but with an envied e-government programme and the birthplace of some big-name tech firms including Skype, it is definitely punching above its weight when it comes to technology.

The president - who himself turned his hands to a bit of coding to fund himself through university - is very clear about where he wants to see education go.

He has the backing of Education Minister Jaak Aaviksoo, a former physicist, who wants to drag the educational system into the computer age.

"It is time for 19th Century educational methods to rise the challenges of the 21st Century," he tells the BBC.

As part of that he has introduced coding into the classroom as soon as children start school, aged seven.

"Kids are very capable and they are already doing complicated things on their tablets and smartphones. If they are used to that then there shouldn't be a gap when they start school.

"School should not be an old-style kind of place but it should build on the potential kids are bringing from home," he adds.

Currently the initiative is being tested but Mr Aaviksoo hopes to roll it out to all primary schools in the next five years.

And Estonia's radical education plans don't stop with coding for seven-year-olds.

Quadratic equations

Do maths lessons need an overhaul?

In February it announced a partnership with Oxford-based computerbasedmaths.org, a group that aims to radically overhaul the way maths is taught in schools.

For British technologist Conrad Wolfram, who founded the group, there is little point in teaching children to make complicated calculations, when they get a computer to do that, and maths should be used more creatively to solve problems that really interest them.

While learning times tables and other basic calculations are necessary in the early years, by the time children get to secondary school, he thinks that the emphasis on complex computations is both unnecessary and likely to turn pupils off the subject.

"It is not dumbing it down, it is making it harder. It also makes it a lot more fun, more geared towards problems that you might want to solve," he told the BBC.

So instead of lessons on quadratic equations, a computer-based maths class would focus on real-world problem-solving, posing questions such as "Am I normal?", "What makes a beautiful shape?" or "Do I need to insure my laptop?"

Estonia is testing the system in 30 of its secondary schools.

"The idea is to use maths as a tool box to solve problems," said Mr Aaviksoo.

He is also considering the idea of letting children bring their own devices to school.

"So many have tablets and other things, although there would have to be provision for those that don't," he said.

New language

In England and Wales, the ICT curriculum is about to be ripped up and replaced by one that Education Minister Michael Gove hopes will both interest young people more and prepare them better for the computer-dominated world of work.

There will be less emphasis on spreadsheets, more hands-on developing and definitely a return to good old-fashioned coding.

For his part, Mr Wolfram thinks that Mr Gove's plans need to go a lot further - and he could start by ripping up the current maths curriculum as well.

"It's great to have coding back on the agenda but I think that coding should be tied to primary school maths," he said.

He doesn't think that such change will happen overnight - in fact he estimates that the changes in the curriculum to reflect the computer age will take 25 years to bed in, but he is hopeful that, in the end, it can create students that are more confident in using the language of coding.

- Published16 May 2013

- Published18 October 2013

- Published12 December 2012