Lifting the lid on a Colossal secret

- Published

A re-enactment of an attack by Colossus on the German Lorenz cipher machine at Bletchley Park

As the code-cracking Colossus celebrates its 70th anniversary, John Cane, a former Post Office engineer who helped maintain it, reminisces for the first time about working on the pioneering machine. His testimony gives a glimpse into the early days of GCHQ's efforts to employ technology in its spying efforts.

When history came calling for John Cane, he thought it meant he was in big trouble.

At the time, in 1943, Mr Cane was a 19-year-old engineer maintaining telephone exchanges for the Post Office.

He had just finished a night shift at an exchange in Battersea and was asked to hang on in the morning as the regional inspector wanted a word.

"I thought, 'What have I done now?'" says Mr Cane.

Nothing, as it turned out. Well, nothing bad. His skill with a soldering iron and toolkit had got him earmarked for a very special project - one that would save countless lives and shorten the war by years.

Park life

Mr Cane was one of a small band of skilled telephone engineers selected to help create Colossus - the world's first electronic, digital computer. The Allies were building the machine to help unscramble the messages passing between Hitler and his generals.

The inspector told Mr Cane he was off nights and should report, complete with tool bag, the next day to Dollis Hill - the Post Office's research station.

"The following morning up I went to Dollis Hill and was shown in to a room there in which were half a dozen people like me in a state of mystification," Mr Cane says.

For the first two days, Mr Cane and his fellow engineers were put to work stripping circuitry off some old iron switching racks.

"Then came the big moment when we were shown in to an office and had a meeting chaired by the then director of Dollis Hill and he told us what we were destined for," says Mr Cane. "We were to build this equipment called Colossus on these racks and that it was really the top secret project of them all, not to be ever mentioned outside to anybody.

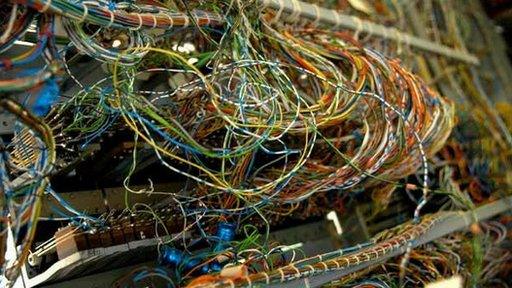

Wiring up the machine was a colossal job in itself

"From then on we kept our eyes down on Colossus and when we finished the wiring on the racks the whole thing was moved to Bletchley Park and we followed it there," he says. "At Bletchley we assembled the racks together, cabled it up and testing began."

The design for Colossus that Mr Cane and his colleagues were working to was drawn up by Tommy Flowers, a senior Post Office engineer who had been helping code crackers at Bletchley with their work. Perhaps unsurprisingly his design was based on equipment found in telephone exchanges and made liberal use of relays, valves and auto-selectors.

Colossus was designed to tackle messages enciphered with what was known as a Lorenz machine that had, unbeknownst to the German generals who used it, a fatal flaw. Bletchley mathematician Bill Tutte discovered a pattern in the encrypted messages that, with the help of Colossus, could be used to unscramble them. It let the Allies read exactly what the Germans were planning and gave them key insights that helped defeat the Nazi war machine.

Secret war

Mr Cane's war was spent at Bletchley maintaining the 10 Colossus machines, known as Colossi, built to crack those messages. All Mr Cane and his 20 colleagues knew was that the machines were cracking codes. The intricacies of how was left to the mathematicians.

Margaret Bullen recalls her time working on the Colossus machine

Talking for the first time to the BBC, Mr Cane says he kept the secret of his involvement with Colossus quiet for decades. He has only spoken about his experiences now as the story of Colossus is slowly being uncovered.

"I'm glad that it has been declassified," he says. "Before then you could not say a word." And he didn't. For decades he "kept his mouth shut" and said nothing of what he worked on to his family.

Mr Cane's testimony also sheds light on what happened to the machines after World War Two. On the orders of Churchill the plans were burned and most of them were destroyed. Most of them.

Two, says Mr Cane, were moved to Eastcote, the initial home of the UK spying effort that would eventually become GCHQ. He took up the offer of a job helping re-house the two machines and kept them running, largely because they were still useful in helping British spies read messages sent by other powers.

Sadly, says Mr Cane, the veil of secrecy that kept it hidden during the war was not maintained at Eastcote.

"One of the blocks we installed this marvellous top secret equipment in had a 3ft (1m) wide hole in the wall," says Mr Cane. "And the children used to climb through that hole and pinch our tools."

After the usefulness of Colossus waned, Mr Cane stayed on at GCHQ, which by then had moved to its current home in Cheltenham. All he can say of that work is that his interest was taken up with "other equipments".

But if little can be said about his later work, more is now being said about the key role he, and those other engineers, played in the Allied war effort. Despite this, he is modest about the significance of that task.

"The way I looked at it was that we'd done a job, enjoyed ourselves doing it and been quite safe," he says. "No-one was dropping bombs on us or doing anything like that."

"There's pride mixed in with that naturally, but it was also a period of technical development and interest that I wouldn't have missed for anything."

- Published9 March 2012

- Published5 February 2014

- Published27 January 2014

- Published24 December 2013