Bill Gates: What Microsoft can learn from its co-founder

- Published

Bill Gates will serve Satya Nadella as an advisor rather than supervising him as chairman

News that Satya Nadella is Microsoft's new chief executive was accompanied by the intriguing development that Bill Gates - the firm's co-founder - has quit being chairman to become a product adviser. He says it will be a more time-consuming role.

Commentators asked, external, was he pushed or did he jump? But a more useful question might be: what does Mr Nadella gain by keeping him around? The BBC asked tech writer Jack Schofield what he made of the move.

As part of the management reshuffle, Gates has resigned as chairman of the board of directors and will work as a "technology adviser", though it's not clear what that means.

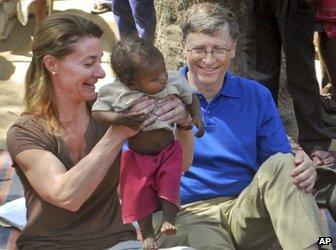

He already has a full-time job, along with his wife, running the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and their focus is on saving the lives of Third World children.

Bill and Melinda Gates founded a charity that aims to help some of the world's poorest people

In any case, today's technology business has changed since the 1970s, when Gates's ambition was to get "a computer on every desk and in every home".

Today, that one general-purpose computer may have been replaced by half a dozen different gadgets with computers inside, such as smartphones, tablets, games consoles, media servers and television set-top boxes.

But there are things that Nadella can learn from Gates's legacy.

Be the underdog

Gates's success came from continually expanding Microsoft's product line into new areas.

The company was set up to sell computer languages such as Basic, but got into operating systems when the giant IBM needed one for its IBM PC.

Gates didn't have time to write one, but he was able to buy QDOS - which stood for "quick and dirty operating system" - and polish it up for release as IBM PC DOS.

It was sold for a quarter of the price of CP/M, a rival's product, and IBM's market power did the rest.

Bill Gates founded Microsoft in 1975 and served as chief executive until 2000

The smart move was that Gates gave IBM a really cheap deal but retained the right to sell the software to IBM's rivals as Microsoft MS DOS.

The result was that Microsoft, not IBM, owned the industry standard.

Microsoft kept expanding into related areas.

First into desktop applications, including Word and Excel, and games. Then server software and applications, with SQL Server and Exchange.

IBM's Personal System/1 computers were powered by a version of Microsoft's MS-DOS

Internet and web-based services, including MSN and Hotmail, followed.

In many cases, Gates took on dominant companies and beat them at their own game: DR and IBM in operating systems, Lotus and WordPerfect in applications, Novell in departmental networks, Netscape in browsers, and a coalition of Unix vendors in server software.

Microsoft is now challenging Sony for leadership of the games market, and Amazon and Google in the cloud.

Microsoft is often the underdog, but it has done much of its best work from that position, and won.

Don't do everything yourself

Outsiders have always had the idea that Gates was responsible for everything at Microsoft, but actually, he hired and backed some very smart people.

Charles Simonyi was the first superstar, hired from Xerox Parc to get Microsoft into applications. This ultimately led to Microsoft Office.

Dave Cutler was the next.

He'd developed a superb minicomputer operating system for Digital Equipment Corp, but they cancelled his next project.

The Microsoft Office suite of applications became the industry standard way to create and edit documents

Gates heard he was upset, and promptly hired Cutler and his whole team.

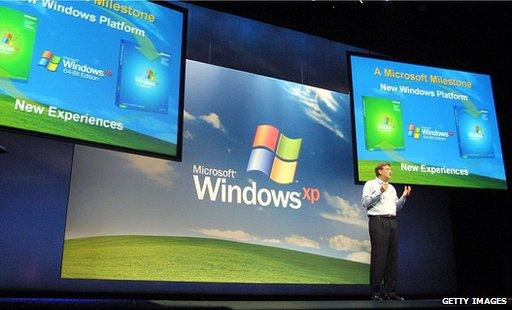

Cutler developed Windows NT (New Technology), which was the foundation for its best-selling Windows XP operating system.

Another key hire was Anders Hejlsberg, who was famous among programmers for writing the Turbo Pascal computer language.

Microsoft lured him on board with a $1m (£600,000) signing-on fee.

He developed the C# language and the .NET Framework, which underlies modern Windows programming.

Gates's approach to management was to hire smart people who, he said, "ought to be able to figure anything out if they get enough facts".

In other words, people like himself.

The origins of Windows XP can be traced back to one of Bill Gates's hires

It helped Microsoft beat IBM, which had been accused of taking a "masses of asses" approach to programming.

As one of the smart people, Nadella could push for more rapid software development in the old Microsoft way, rather than the IBM way.

Avoid Gates's mistakes

Bill Gates was very quick to see - indeed, create - the market for PC software, but sometimes his timing was poor.

Compaq was among the firms to launch a Web Companion computer, but the devices proved unpopular

He was slow to wake up to the power of the internet, and had to play catch-up, while in other cases he was too early.

For example, Microsoft launched Web Companions - internet-dependent computers which were similar to Google's Chromebook laptops, only better - in 1999; touch-screen smartphones in 2001; and tablets running Windows XP in 2002.

None of them made it big, and Microsoft had to suffer the ignominy of Apple arriving later and achieving huge success with much more appealing products.

Can Nadella do better?

It will be tricky because the market has turned upside down.

Gates's Microsoft targeted businesses in the knowledge that, when prices fell, they would appeal to consumers.

Today, consumers decide what they want and companies follow, if they can.

Mr Gates faced allegations that Microsoft had abused its operating system monopoly in 1998

Nadella got the chief executive gig by running Microsoft's Cloud and Enterprise division, not one that provides consumer products.

One mistake Nadella should avoid is the anti-trust problem.

Gates's Microsoft suffered numerous government attacks for its monopoly of the PC industry, and his testimony in the 1998 US trial looked resentful at best.

He clearly had better things to do with his life.

He soon resigned as chief executive, and started to shift his time and energy to his charitable foundation.

Microsoft now knows that monopolies are held to different standards from scrappy underdogs, but again, times have changed.

Attention has switched to smartphones, tablets and internet services where it is still a minor player, and is not seen as a threat.

Which future?

There is no shortage of products that could absorb Mr Gates' time

Nonetheless, Microsoft does have a solid strategy in the "three screens and a cloud" idea articulated by Ray Ozzie, another - albeit temporary - superstar hire.

The cloud, Azure, is looking good, and the three screens are coming together with Windows 8 (PCs and tablets), Windows Phone 8 (smartphones) and Xbox One (TV).

Mr Nadella's predecessor Steve Ballmer had a tough time with the Windows Phone platform

That's a viable future if, and it's a big if, Nadella can execute it well enough.

The alternative preferred by some investors is to sell off everything else and milch the enterprise market, which would put Microsoft into a long, very profitable but possibly fatal decline.

That's not a mistake Gates would make, but does he still have the power to prevent it?

Jack Schofield has covered the tech industry since the 1970s and served as the Guardian's computer editor until 2010. He still writes the Ask Jack blog, external for the paper.

- Published4 February 2014

- Published4 February 2014

- Published4 February 2014