Next Silicon Valleys: How did California get it so right?

- Published

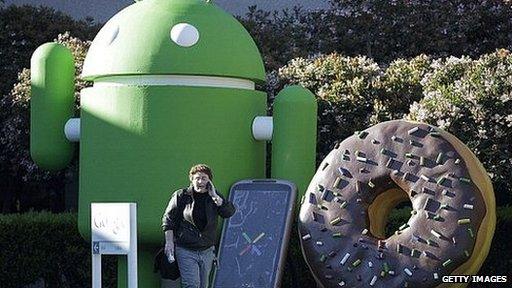

California's Silicon Valley is much envied

From Hewlett-Packard to Google, from Apple to Intel - the many start-ups created in Silicon Valley have helped define the modern world.

The area - surrounding San Francisco Bay in northern California - has arguably been the world's supreme entrepreneurial hotspot, generating a seemingly endless supply of new technologies, new companies, and huge wealth.

But now, other places around the world are trying to create start-up clusters of their own. Next week, the BBC will start a series looking at other areas trying to replicate Silicon Valley's success.

Ahead of this, we asked a range of experts from Silicon Valley why they thought the area had been so successful - and what advice they would give to those keen to emulate its achievements.

Vint Cerf, Google

Silicon Valley is a unique amalgam of academia, private sector and US government research investment coupled with a population of (serial) entrepreneurs.

It began with Fred Terman, Provost at Stanford, who recognised that federal investment in research led to the winning of WW2.

He leveraged this to expand the engineering department at Stanford by a factor of three and encouraged graduates, such as Hewlett and Packard, to start new companies.

What results is a steady stream of well-trained engineers, business people, marketers, researchers; a vibrant venture capital community; a highly available stock market appetite for stock flotations; and people with experience in business, including how and why business failures happen.

Importantly, business or technical failure is considered experience and not an indelible mark of incompetence.

The Valley is a small place. People know each other: they have worked with one another, or managed or worked for one another.

Forming a new business is pretty easy under Californian law.

It is altogether a remarkable, vibrant and innovative culture that continues to produce dividends decade after decade.

Michael S Malone, technology journalist and author

Silicon Valley is not so easy to replicate.

One reason is time: the Valley is also the oldest high-tech community on Earth. Begun in the Packard garage seventy-five years ago, it has had more than seven decades to figure out every nuance and fill every niche of the digital world.

A second reason is location: Silicon Valley, as Santa Clara Valley, was a largely unpopulated agricultural area at the end of WW2, with cheap land and a great city nearby.

It benefited greatly from the migration of Americans, especially veterans, west to California and into the new jobs in aerospace and electronics.

The third reason is infrastructure: there are few places anywhere that offered a full range of educational institutions from trade schools, to mid-level colleges, to the two great universities, Stanford and Berkeley.

All of these factors combined to create a fourth reason for the success, and singularity, of Silicon Valley: culture.

The Valley didn't come freighted with old attitudes and cultures, but was free to create one of its own: risk-taking, multi-cultural, meritocratic and most of all, entrepreneurial.

Underlying everything is an acceptance - even an admiration - of good failure.

Paul Saffo, Discern Analytics

The secret to Silicon Valley's success? We know how to fail and we have been doing it for decades. Failure is what fuels and renews this place. Failure is the foundation for innovation.

Failure is essential because even the cleverest of innovations - and businesses - fail a few times before they ultimately succeed.

Consider Google: at least half a dozen other companies tried to turn search into a business, but Google was the first to crack the code and turn search into a huge business.

And even when companies succeed, the only way to survive in the long term is to flee into the future by relentlessly innovating.

Apple all but killed off the iPod at its peak by turning the iPod's music function into a feature incorporated into the iPhone when it was introduced in 2007.

Apple happily killed its own product because if Apple hadn't done so, another competitor would have done it for them.

Failure is what makes Silicon Valley's success to hard to replicate. Would-be competitors only see, and try to copy, the Valley's success.

But to succeed you need an ecology of fearless players from venture capitalists to banks, suppliers and myriad other supporting businesses unafraid to risk all by helping with often flakey and unpredictable start-ups.

So if you want to be the next Silicon Valley, don't copy our success. Learn to support and encourage novel and ultimately successful failure.

Vivek Wadhwa, entrepreneur, academic and author

Regions all over the world have tried to copy Silicon Valley, but none has succeeded.

That's because they have focused on trying to recreate its venture capital system, universities, or start-up incubators.

What they don't realise is that what really makes the Valley tick is its culture of risk-taking and information sharing; people-to-people networks; openness to new ideas; and diversity - more than half of its innovators are foreign-born.

It also helps that Silicon Valley has excellent weather, is close to mountains and the ocean, and has a myriad of state-park hiking trails - these help foster a culture of optimism, openness, tolerance, and sharing.

These are the ingredients that can't easily be recreated.

Venture capital only follows innovation, it goes where the opportunities for building wealth are, it doesn't create new opportunities.

So this shouldn't be the starting point in attempts to build an innovation ecosystem.

Any region wanting to build its version of Silicon Valley should focus on its people and culture.

Judy Estrin, serial entrepreneur

Silicon Valley is a unique combination of universities, companies, venture investors, culture, weather, all sorts of things that come to play to create Silicon Valley.

Typically if you look at the places where you have entrepreneurial ecosystems, there are at least two universities. Those students carry ideas into the world.

You need to have at least one or two big companies because often entrepreneurs are people who work in a big company and come up with an idea.

The big company rejects it because it's not part of the large firm's objectives. As a result, the entrepreneur leaves that company and does it on their own.

So you need big companies to provide both talent and ideas and infrastructure and then you need the right policies and incentives.

It's about making sure that you don't have policies that are making it too hard to start a business.

So it's a combination of things that you can try to reproduce Silicon Valley.

Will you get exactly Silicon Valley?

No. But you might get the equivalent of that entrepreneurial ecosystem, but for a different area - maybe for healthcare, maybe for the food industry, maybe for farming.

The Next Silicon Valleys is an eight-part series broadcast on BBC World News on Mondays at 06:55, 08:55, 13:50, 15:50 and 19:50 (all times GMT).

- Published3 September 2013

- Published26 November 2013

- Published17 October 2013

- Published27 August 2010