Next Silicon Valleys: Beijing's start-ups show stamina

- Published

Neil Koenig visits Beijing to see how it compares with its Californian counterpart

Beijing has a thriving start-up scene, and some of its entrepreneurs are going to extraordinary lengths to ensure their success. As part of our Next Silicon Valleys series, Neil Koenig visits to see how it compares with its Californian counterpart.

There's no doubting the dedication of some Chinese entrepreneurs. Chai Ke insisted that he and his team (all men) should wear sanitary napkins for several weeks to help them empathise with their customers and so develop a better product - a menstruation-tracking app.

Chai Ke insisted that he and his team should wear sanitary napkins

Mr Chai's company, Dayima, is one of a number of firms that offer mobile phone apps to help women in China to track their periods.

Dayima (which means "auntie", and is also a slang term for "period") has raised millions of dollars from international investors, and says it has millions of users.

Basic use of the app is free. Users enter various details, such as their weight, into the app, which it uses to help it predict (with varying degrees of success) when the next period will occur. The company makes money through advertising and by selling extra services and products.

Mr Chai hit on the idea of the menstrual tracking app after his girlfriend told him about her own difficulties with keeping track of her periods.

He says Westerners are often puzzled why there should be demand for his service.

He says it's because it's not always easy for Chinese women to track or predict their periods.

Garage Cafe is a place where investors and entrepreneurs can meet

Although official figures are hard to come by, Mr Chai says that while his Western female friends say their periods are reasonably regular, the Chinese women he knows say their cycles vary considerably.

The reasons for this are unclear, but Mr Chai wonders if it might have something to do with differences in lifestyles and attitudes to health between East and West.

He adds that they've noticed differences in the cycles of users from various parts of the country. Dayima has therefore developed a set of prediction models tailored to users in various cities, such as Beijing or Shanghai.

Cafe culture

Dayima is just one of a plethora of new companies to spring up in Beijing in recent years. Many are clustered in Zhongguancun, a district in the west of the city, where computer giant Lenovo was founded in the 1980s. The area is now home to many big tech companies, keen to hire graduates from the nearby universities.

Zhongguancun is blessed with "the greatest number of talented people in the whole of China", according to the entrepreneur Su Di.

Deep Glint has moved into an apartment in the suburbs

He used to work for an investment firm, looking for promising start-ups to back, but found them widely scattered across the city. So he launched Garage Cafe as a place where investors and entrepreneurs could meet more easily.

One of his customers, Simon Liu, recently founded a software company EEPlat with someone he met in the cafe.

Mr Liu's venture aims to help businesses manage their data more effectively. He says he's ready to compete with the biggest players in the world: "A big company like IBM fears small start-ups like mine, because my idea is so crazy - and only the craziest ideas pay the best."

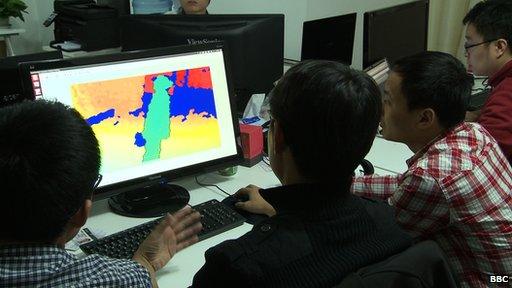

Deep Glint wants to teach computers to see in the same way as humans

Home comforts

But as Zhongguancun grows in popularity, some start-ups have been forced to look for cheaper locations elsewhere in the city. The government has helped by allowing companies to set up in apartments rather than in offices.

"It's five times cheaper than an office - and it's much nicer too," says Zhao Yong. His start-up has recently moved into an apartment in the suburbs near the Olympic Park.

Mr Zhao has big ideas for his company, Deep Glint. The firm wants to teach computers to see in the same way that humans can.

Deep Glint uses special cameras and software that will enable to computers to "see" the world around them, and to interpret what they are seeing.

Potential future applications for the technology include robotics and driverless cars.

ZhenFund general manager Anna Fang says China's attitude to risk needs to change

Despite this thriving start-up scene, Anna Fang, general manager of ZhenFund, which has backed both Deep Glint and online education firm Sunny Education, says China will have to change its attitude to risk if it is to truly rival California's Silicon Valley.

"In Silicon Valley when you fail it's seen as a good thing. Oh, you've learnt so much, what's your next thing going to be? And in China, failure is still seen as a negative, and I think that attitude needs to change for there to be more innovation."

- Published7 February 2014

- Published14 November 2013

- Published27 January 2014

- Published25 January 2013