Next Silicon Valleys: Speed reading and life-size robots

- Published

Richard Taylor visits some of the start-ups in and around Boston

Boston's tech scene is taking off. Richard Taylor looks at how it has become a front-runner to rival California's Silicon Valley.

Imagine reading the next web article twice as quickly as this one - and understanding more of it too.

That's the claim made by Boston-based Spritz, external, which aims to revolutionise speed reading one word at a time.

Drawing on science established in the 1960s, the premise is that by flashing up single words in quick succession and allowing your gaze to remain largely in the same place on a screen, the brain can digest information far more effectively than your eye scanning across a page.

Samsung will incorporate Spritz's speed-reading tech into its Gear smartwatch

Counter-intuitively, the faster you read using the method, the more you understand, because you are apparently more focused.

Admittedly, "Spritz-ing" does take a little practice, and it is better suited to emails and web pages than novels, where a more leisurely approach might be called for.

Try it for yourself by clicking on the Spritz demo button. , external

Having spent three years in "stealth mode" developing the tech, the start-up made headlines last month when Samsung said it would incorporate the tech into its Gear, external smartwatch, its small screen ideally suited to the concept.

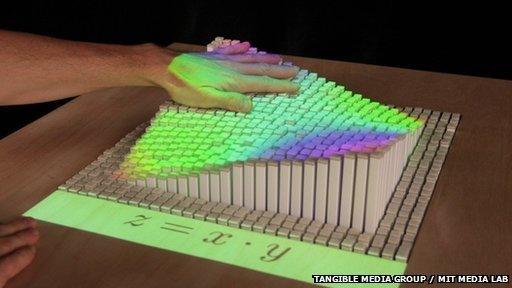

inFORM could help designers collaborate from afar

In the week following the announcement, Spritz's founder Frank Waldman tells me that he had to speed-read his way through more than 7,000 submissions from software developers wanting to incorporate his breakthrough.

The power of MIT

Mr Waldman, like so many in the region, hails from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), external, just across the river from Boston, in Cambridge.

For 150 years MIT has been turbo-charging Boston's tech engine.

Its influence is hard to overstate: MIT alumni have produced companies that generate annual world revenues of $2 trillion, external (£1.2 trillion), with hundreds of patents ranging from biotechnology to computing.

And looking to the future, the region looks to be strategically well-placed.

"Because innovation is moving towards a hybrid model of the digital and the material, Massachusetts is once again a place for that, because this is a place where we actually make things," argues Fiona Murray, dean of innovation at MIT.

One particularly fascinating project is called inFORM, external

Take a 3D camera to capture your hand gestures, relay the information over the internet and convert it back into physical movement; a matrix of 900 pins driven by small motors rises or lowers to simulate your original movement.

If the project sees the light of day, it means designers could collaborate from afar on physical projects.

Telepresence robots

Many MIT projects do come to fruition. In a similar model to that used by its Silicon Valley rival Stanford, students work closely with faculty to turn projects into viable start-ups.

iRobot has developed life-sized telepresence droids

That was how MIT alumnus Colin Angle began iRobot, external 30 years ago.

iRobot's focus is on autonomous robots, like small domestic floor-cleaning devices, but it has recently developed life-sized telepresence droids.

One helps businesspeople remotely wander around their office; another administers "telecare", letting medical specialists thousands of miles away scour hospital wards and dispense expert advice to nurses on the ground - after zooming into the whites of a patient's eyes and checking their vital signs.

iRobot is located along the famous Route 128, a Boston ring-road that became synonymous with hi-tech towards the end of the last century.

Appetite for risk-taking

Now everywhere you go there is a sense of newfound optimism that, after a period in which the emphasis of tech has shifted to the West Coast, the greater Boston area is set to make real headway again.

"What Boston didn't figure out in the 1990s and 2000s is how to build technology for consumers," observes Scott Kirsner, tech correspondent for the Boston Globe.

"It's why Apple and Google aren't here. But we're starting to figure that out - we have some very fast growing e-commerce, social and user-generated content here."

Locals admit that Boston has not shouted about its success stories in the way Silicon Valley does - perhaps because it lacks huge, defining tech totems to capture the popular imagination.

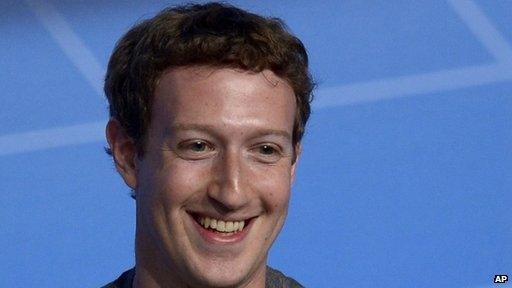

Mark Zuckerberg started Facebook from Boston's Harvard

What grates here is that Mark Zuckerberg famously started Facebook from his Harvard dorm room, but before long took the social network to the other side of the country, where both huge sums of venture capital and a voracious appetite for risk-taking prevail.

But in a sign of Boston's nascent resurgence, Facebook has now returned with a small outpost in the Cambridge tech hub Kendall Square, just down the road from Harvard.

It nestles in a cluster alongside other Silicon Valley behemoths like Google and Twitter.

Still, all too often Boston start-ups end up being snapped up by their bigger, West Coast brethren; witness Google's recent purchase of another local robotic success story, Boston Dynamics, external.

The challenge for Boston, it seems, is not just to develop the talent, but to hold on to it too.

- Published7 September 2013

- Published29 August 2013

- Published3 March 2014

- Published21 January 2014