Mini-satellites send high-definition views of Earth

- Published

Richard Taylor reports on the low-cost satellite technology providing revolutionary ways to view life on Earth.

Imagine being able to monitor deforestation tree by tree - and act accordingly.

Or, as a farmer, remotely monitoring the health and yield of crops on a daily basis over huge swathes of land.

Perhaps as an aid agency, effortlessly estimating the flow of human traffic across borders over the course of a week.

And for business retail analysts, estimating the footfall of a retail chain by counting the sheer number of vehicles in its car parking lots across a region.

These are just some of the countless possibilities conceivable when our world is observed from on-high every day or week, rather than the years it can currently take to completely update our planet's imagery on services such as Google Earth.

Soon these possibilities will translate into reality, as a new image-focused space race is steadily gathering pace.

Rather than being conducted by nation-states or mega-corps, it is being played out by Silicon Valley tech start-ups doing what they do best - defying conventional thinking to disrupt an entire industry.

Their goal is to reveal an unprecedented understanding of activity conducted on Earth by taking and analysing pictures of our planet in its entirety.

The dove cubesats were launched from the International Space Station

The new building blocks of this revolution are tiny - a fleet of shoebox-sized "cubesats" - cheap, miniature satellites, developed over the past decade in universities to aid space research.

From a characteristically untidy San Francisco start-up office no larger than a family home, Planet Labs' 40-strong team of 20 and 30-somethings is making the largest constellation of satellites the world has ever seen - 131 planned in the next 12 months, to give a comprehensive snapshot of Earth almost daily, with pictures sent back for analysis within hours.

"We're basically leveraging billions of dollars that has been spent in consumer electronics to advance space exploration and the capabilities of satellites to help people on the planet," says British co-founder and chief executive Will Marshall.

In February the first few in its initial batch of 28 were ejected out of an airlock on the International Space Station. These cubesats - called "doves" in line with their peace-harbouring ambitions - are now sending back their first images from low-Earth polar orbit, passing over Earth at five miles a second.

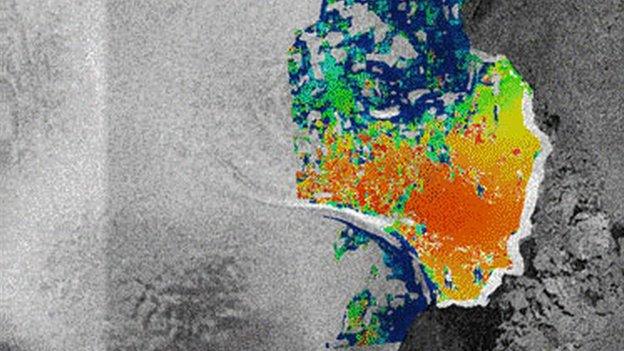

The pictures are detailed enough to pick out individual trees (although not individuals, addressing objections from privacy advocates) - which will give an unparalleled insight into activity on the planet's surface.

The company says its mission is ultimately to democratise access to information about our planet. "Instead of seeing a hole in the Amazon a few months after trees have been taken down there, we can see it as it's happening", says the Planet Labs co-founder.

Although the company plans to give away valuable data to NGOs (non-governmental organisations) and other suitably worthy causes in line with its humanitarian aims, Planet Labs sees no contradiction in being first and foremost a profit-making concern, backed by venture capital and already attracting paying customers.

The satellites are cheap to replace if they fail

A makeshift clean room separated by plastic sheeting from the main office is where off-the-shelf components from camera lenses to solar-charged batteries are assembled into the finished product sheathed in solar panels.

The entire package measures just 10cm (4in) by 10cm by 30cm. "Nowadays we put more capability into these little satellites than you can possibly imagine - into something just a few kilos much more capable than a satellite a few years ago that was 10 tonnes," says Mr Marshall.

With only basic manoeuvring capabilities and cheap sensors these cubesats clearly do not conform to the same rigour as conventional satellite-construction - but then again, the cost of a cubesat satellite failure comes is in at thousands of dollars, not hundreds of millions.

"If we lose a satellite, it's a bad day in the office but not a catastrophe," Mr Marshall says.

Conflict zone

Satellite images in high-definition can give unprecedented levels of detail

But this revolution in satellite imaging is not confined to still pictures.

Other start-ups, such as Skybox and Canadian Urthecast, are focusing their efforts on high-definition video, with far bigger fridge-freezer-sized satellites equipped with more powerful telescopes capturing far more detail than those capable in mere cubesats.

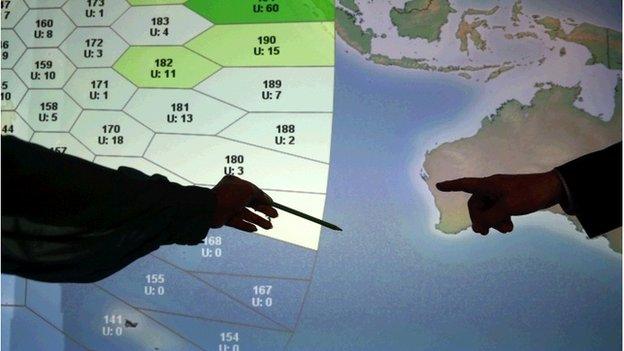

At a resolution of just over 1m per pixel, the most powerful on-board telescopes can track single cars travelling along a road, or groups of people gathering.

Skybox's first satellite of a planned fleet of 24 launched in December.

Flying in low-Earth orbit around Earth 16 times a day, it is now relaying 90-second black-and-white clips, which, cloud-cover permitting, allow unprecedented analysis of movement on Earth.

"If you show someone a still image of an area they can gain some understanding of what's happening," says Skybox founder Julian Mann. "But if you show someone even a few seconds of video we intuitively understand more."

The use cases here for deep analysis are compelling - everything from natural disaster relief to supply-chain monitoring of commodities or broadcast news coverage of conflict zones.

Urthecast delivers its so-called "ultra-HD video" in colour - and plans to open up its platform to individual consumers to be able to observe their own backyards.

Pandora's box

There is no doubt as to the potential these systems offer.

But they also leave the door open to misuse of the technology - not for the benefit of our planet or humanity but for self-centred interests ranging from corporate espionage to greater control over rebel insurgency.

Thomas Immel has spent two decades as a scientist at the Space Science Laboratory at UC Berkeley.

"These new capabilities open up a Pandora's box," he says.

"Some applications may well be harmful or controversial.

"What is clear is that 10 years from now we'll be having another argument over the next implementation of technology that we can't even imagine."

Some consequences may be easier to predict - like attracting the attention of bigger technology firms.

Skybox is already rumoured to be in early-stage acquisition talks with Google, which bought drone start-up Titan aerospace earlier this year, following hot on the heels of Facebook's purchase of UK-based drone maker Ascenta.

Silicon Valley's behemoths clearly have stellar ambitions of their own - and the newfound opportunities presented by Earth-observation may well prove too tempting to resist.

You can see more about space technology on this weekend's episode of Click.

The following link provides the show's broadcast times in the UK and on BBC World News.

- Published12 May 2014

- Published10 May 2014

- Published8 May 2014