Tiny KickSat Sprite satellites hitch ride into orbit

- Published

A crowd-funded project, Kicksat, is planning to send a hundred tiny satellites into Space.

Exploring space has long been the sole diversion of governments, big business and academics.

With each galactic jaunt potentially costing hundreds of millions of pounds and demanding decades of planning, it's hardly a surprise that we're not all reaching for the nearest astrophysics textbook.

As of this week, however, 104 regular Earth citizens can now claim to each have had their own satellite in orbit, each for less than £200 ($300). The age of personal space exploration has begun.

The space pioneers are all backers of the KickSat project.

Started in December 2011 on the crowdfunding site Kickstarter, the project attracted more than double its initial asking amount, pulling in nearly $75,000.

Three years later, KickSat's 104 satellites have hitched a lift into orbit aboard SpaceX's CRS-3 resupply rocket to the International Space Station.

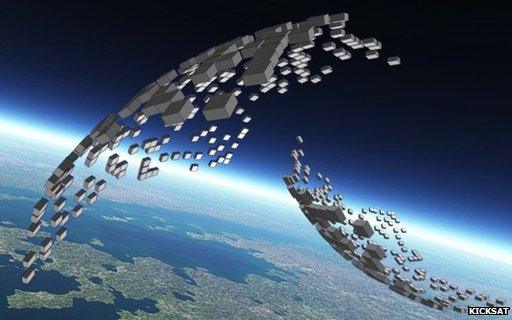

The big idea behind KickSat is to make satellites so tiny that the cost of getting into space can be split hundreds or even thousands of ways.

Tiny tech

The major expense of space flight, perhaps unsurprisingly, is getting off the Earth - typically it costs up to $100,000/kg to ride a rocket into space.

The KickSat satellites, called Sprites, are drastically different to the large and costly satellites currently orbiting above our heads.

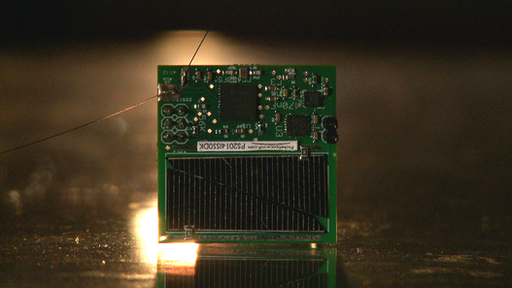

Weighing 5g (0.18oz) and small enough to fit in the palm of your hand, Sprites only exist thanks to the progress made in the miniaturisation of electronics.

The Sprites are circuit boards fitted with processor chips, solar cells and antennae

Much like the diminutive Raspberry Pi computer, plenty of computing grunt can now be packed into a comparatively small area.

The brains of the Sprites are roughly as big as a fingernail, but are about as powerful as the entire computing system on board each of the Voyager space probes launched in the late 1970s.

Combine this with cheap off-cuts from space quality solar panels, a few other small instruments and memory wire antennae, and you have a tiny satellite capable of transmitting data back to Earth.

Standard Sprites only collect a relatively limited amount of data - such as temperature, and magnetic and orientation information - but even this, when collected in large numbers, can be useful.

"One instrument by itself might not be very high quality but in aggregate, by the hundred or by the thousand, you can take measurements that you can't necessarily get in any other way," Michael Johnson, co-creator of the KickSat project, tells BBC Click.

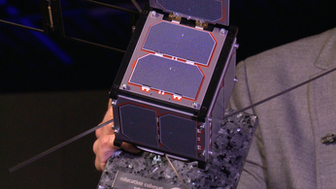

The Sprites were ejected from a CubeSat - a small satellite carried into space in the cargo hold of a mission to the International Space Station

"For example, instead of having to land a large rover on a planet you might instead land a few thousand very small spacecraft all around the surface.

"As they get blown around by weather systems they will go to places that a rover couldn't even get to."

Just like a Raspberry Pi, the programming of the Sprites can also be customised to perform new and novel tasks.

Space debris

Luke Bussell, a sixth-former from York, heard about the KickSat project whilst studying for his astronomy GCSE and ended up programming his own Sprite.

By watching for unexpected changes in the Sprite's memory, he was able to turn the satellite into a cosmic ray damage detector.

Prof Alan Woodwood, from the department of computing at the University of Surrey, welcomes the idea of schoolchildren like Luke being able to achieve such scientific dreams. But he remains concerned about the prospect of increased access to space.

"It's getting very crowded up there, and it's a bit of a Wild West," he says.

"There is a responsibility that not too much goes up by the people putting things up there.

Michael Johnson hopes to inspire students and enthusiasts with his space projects

"There's always a risk that they could damage a communications or weather satellite. If care isn't taken, problems of debris and space junk could become a lot worse."

Mr Johnson says he has taken this into account by designing a limited lifespan into the Sprite satellites. Within a few weeks of launch all of them should re-enter the Earth's atmosphere and burn up.

However, if citizen space exploration does become more common, it could become a problem.

Mission to Moon

For enthusiasts like Luke and Mr Johnson, projects like KickSat are only the beginning of an era of personal, open-source space exploration.

Many of the lessons learned from the KickSat mission are being used to inform Michael's next project, PocketSpacecraft, which has even grander ambitions.

104 tiny Sprite "spacecraft" have been placed in low Earth orbit

"There are more than a million bodies in the solar system worth exploring, whether that's planets, moons, asteroids or comets, and since the beginning of the space age there's been about one Earth escape spacecraft launched every year to go out and do some exploration," says Mr Johnson.

"The science done is incredible, but we're never going to explore a million bodies in the solar system at a billion dollars a time, there simply isn't enough money in the world."

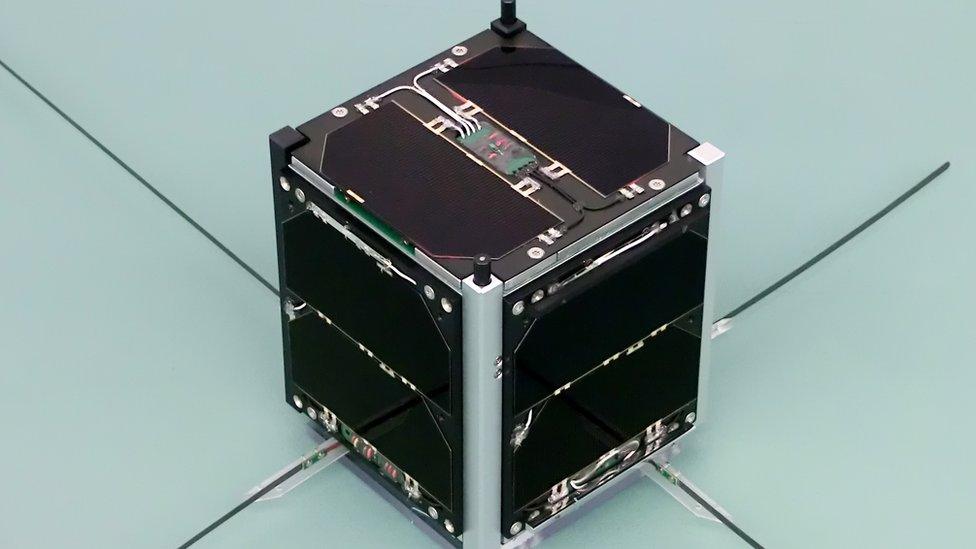

Aiming to launch in 2015, the team at PocketSpacecraft are working on an even smaller satellite design, called a Scout, that they hope will travel all the way to the Moon.

With an average thickness of 20 microns (0.02mm), the Scout is designed to allow thousands to be packed into a single launch, reducing the costs per satellite considerably.

PocketSpacecraft's Kickstarter campaign missed its target

The design also makes use of printable electronics, and a technique called lapping - removing excess silicon from the core chip - to minimise thickness and weight as much as possible.

Even the memory metal aerial is put to good use, doubling up as as a structural support for the Scout by looping around its edge.

Looking to the future, Michael says the ultra-thin Scouts may eventually be able to ride the light from the Sun to distant parts of our solar system, steering by changing their reflectivity with LCD shutters.

Although PocketSpacecraft's Kickstarter campaign failed to hit its target, Mr Johnson has since managed to attract the $500,000 needed to fund the mission.

He acknowledges, however, that there is no guarantee of success.

"One of the things we're very clear about is this is hugely risky," he says.

"If you're doing billion-dollar missions roughly 50% of them fail… so failure is an option.

"We try to have as many alternative ways as possible of getting data back from these spacecraft, so that at whatever point we get to, we'll get some useful return from the mission."

- Published16 May 2014

- Published21 November 2013

- Published29 May 2012