Mortal Kombat: Violent game that changed video games industry

- Published

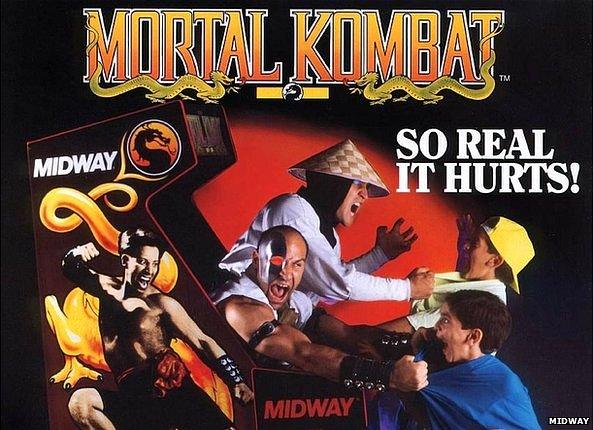

Mortal Kombat's original adverts featured young players, suggesting they were part of the target audience

Warner Bros has confirmed it plans to release Mortal Kombat X next year, the latest edition in a video game series that has stoked controversy and allured fighting fanatics for more than 20 years.

It will be the first title offered, external on the "next-gen" PlayStation 4 and Xbox One consoles - and if the trailer is anything to go by, external there's little doubt it will display the game's gruesome attacks in greater detail than ever before, causing fresh fuss.

Even so, it will prove difficult to trigger the scale of outrage that accompanied the original game.

In the summer of 1993, the Nintendo executive Howard Lincoln had come up with a controversial solution to an unavoidable problem.

His company, renowned for creating entertainment that is cherished by children and trusted by parents, was preparing to release Mortal Kombat, considered one of the most violent games ever, on the Super Nintendo console.

It was the equivalent of Disney distributing Reservoir Dogs, American Psycho on Sesame Street.

The first Mortal Kombat game was released in arcades in 1992 and on consoles the following year

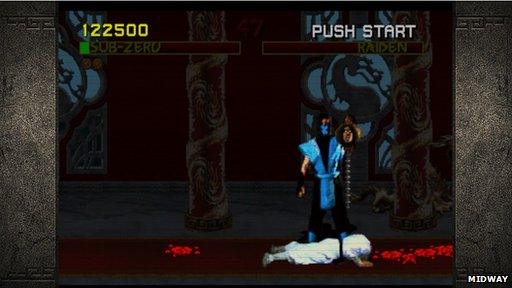

Mortal Kombat was admired by critics but inevitably better known for its unashamed glorification of murder.

It allowed combatants to rip the heart out of a vanquished foe, or tear the head off a fallen opponent, and hold the appendage up as a trophy.

The game encouraged players to do this with the infamous message "Finish him!" that would repeatedly flash on the screen when a bout was over.

How could a game like this, regardless of how popular it was, be sold on shelves next to Super Mario World?

Go green

Months after Mortal Kombat's initial release across arcades in October 1992, and before its port onto the Super Nintendo, Mr Lincoln met Acclaim chief executive Gregory Fischbach to offer a solution.

Acclaim chief Gregory Fischbach was asked to change the blood in Mortal Kombat from red to green

"Lincoln told us we needed to change the blood from red to green, which I thought was pretty stupid," Mr Fischbach tells the BBC.

Not only that, but the game's fatalities would be edited, and various background details - such as heads impaled on spikes - would be completely removed. Mr Fischbach believes such decisions were rash, but was unable to block them.

"To my mind, Mortal Kombat was comic-book violence, but some people got upset about it. People looked at it as though we were selling it to nine-year-old children."

The wider issue was that Mortal Kombat had arrived during an era of transition for the games industry.

What was considered a child's pursuit had begun to serve the interests of young adults and teenagers. Those audience clashes had naturally begun to manifest.

"It was the beginning of video games coming of age," says Mr Fischbach.

"At one point in time, games were just meant for children, and nobody really took them seriously. But it was with the launch of Mortal Kombat that people who controlled the media began to look at it differently."

Mortal Kombat character Sub Zero could rip the head off his vanquished opponents

Even though games such as Mortal Kombat, Doom and Night Trap were created for mature audiences, crucially there was no law preventing young people from accessing them.

This led to thunderous denunciations from politicians and news media anchors alike.

"Part of the problem at the time was that the biggest distributor of games in the US was Toys R Us. The positioning in the marketplace was that games were designed for children, and not teenagers or young adults."

Blood money

Nintendo's efforts to censor Mortal Kombat failed to put a lid on the controversy.

Rival company Sega had also published the game on its own system, the Genesis (known as the Mega Drive in the UK), and via a cheat code allowed gamers to enjoy the gore-fuelled glories of the arcade original.

Blake Harris remembers that Sega's version of Mortal Kombat could be made more bloody than Nintendo's

According to Blake Harris, author of Console Wars, Sega's gamble paid off enormously.

"The net result was that the Sega Genesis version of Mortal Kombat outsold the Super Nintendo version five-to-one," he tells the BBC.

It was the Genesis version that also caught the eye of one young Mortal Kombat fan who happened to be the son of a Capitol Hill aide.

According to Mr Harris, this simple connection is what could have triggered the political outrage against violent video games.

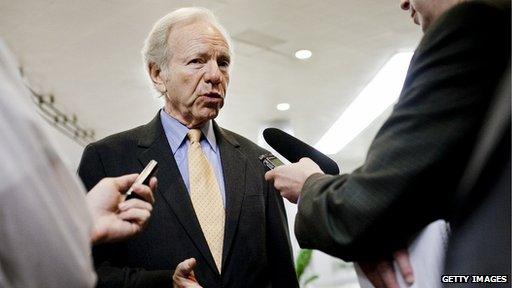

"Bill Andresen, a former chief of staff to Senator Joe Lieberman, was asked by his son to buy Mortal Kombat. But when Andresen saw the game, he showed it to Lieberman, who was appalled by it."

Reform calls

On 1 December 1993, Mr Lieberman gathered the Washington press corps to expose what he believed was the corrupting influence of video games on young minds.

The last main game in the franchise was released for consoles in 2011

He played several VHS tapes, showcasing some of the goriest elements of games such as Mortal Kombat and Night Trap, and announced his intention to introduce a game age-ratings body.

"Few parents would buy these games for their kids if they knew what was in them," he said at the time.

"We're talking about video games that glorify violence and teach children to enjoy inflicting the most gruesome forms of cruelty imaginable."

John Tobias, one of the four developers who created Mortal Kombat, believed the reaction was harsh.

"Their lobbying never felt sincere. To me it always felt like scapegoating an industry they knew nothing about to pander for votes," he tells the BBC.

"Anyone who listened to the testimony or the questioning that went on and who knew anything about games understood that.

"Video games were not and never will be the great destructor of society they were trying to paint them to be."

Senator Joe Lieberman held a hearing into video games after Mortal Kombat's launch

One week after Mr Lieberman's press conference, the senator chaired a subcommittee on violent video games, insisting that the industry must introduce a system of self-regulation if it wanted to avoid state regulation.

Nintendo's Japanese versions of Mortal Kombat 2 featured green blood

Within five months, the games industry established the pioneering Entertainment Software Rating Board, and one of its first acts was to assign Mortal Kombat a "mature" rating, meaning it was illegal for minors to purchase it.

Moral panic

These events, spurred by moral panic, painted the games industry in its most unflattering light, but nevertheless established a ratings code that is still adhered to today.

Mortal Kombat 10, announced today, is certain to be the next entry in the series designated an M-rating.

On reflection, Mr Fischbach believes the ratings reform "was the right thing to do".

He says: "It allowed game creators and publishers to focus on what they do, and allowed information to be displayed on game packaging that wasn't there before."

Despite weak reviews, the Mortal Kombat movie in 1995 spawned a sequel

But Mr Harris believes that, however beneficial the outcome, the calls for game age ratings was not as driven by the public as often suggested.

"I think the outrage was mostly from the media. I think parents, for the most part, still didn't realise what video games were," he says.

"I could be wrong, but I spent three years researching this, and not once did I get the sense that people were spurred on by angry calls or angry letters from the parents.

"I mean, Lincoln told me that he got numerous angry letters from parents, but it was people complaining about Nintendo censoring their games. They didn't like the green blood. I think that tells you how much this issue was media-driven."

- Published27 May 2014

- Published13 May 2014

- Published7 April 2014