Hiding currency in the Dark Wallet

- Published

The squatting developer behind the new Bitcoin tech Islamic State want for money laundering.

What if the software you developed ended up being used by extremists?

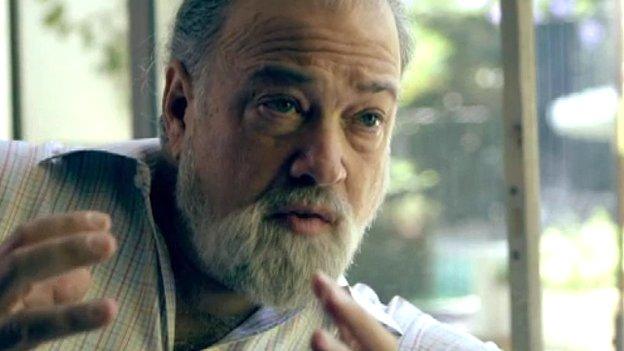

Amir Taaki is one of the key programmers behind a tool which could potentially hide the identity of people using the crypto-currency Bitcoin.

Along with Cody Wilson, the man who caused headlines for creating a 3D-printed gun, he has made the Dark Wallet.

The aim of the Dark Wallet is to make transactions done with the crypto-currency Bitcoin almost impossible to trace.

The US government and European Banking authorities are looking at regulating the use of the crypto-currency, and are particularly concerned about how the Dark Wallet could be used as a money laundering tool.

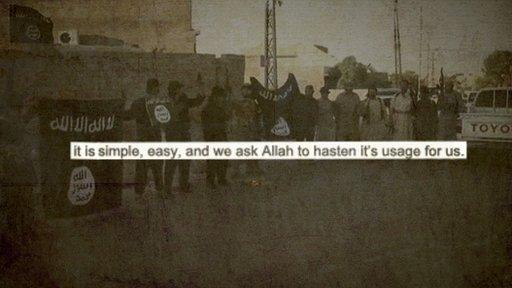

Recently those fears intensified when a blog about the technology was published and shared online. It discussed how extremists such as IS could maintain an anonymous online presence.

The blog has not been verified - but it supported the idea of the extremist group's mission in Syria and Iraq.

It provided a step-by-step instruction guide to staying anonymous online, including how to use the anonymising Tor network - one of the ways people connect to the so-called "dark web" - and virtual private networks (VPNs) that are used to help hide people's location and identity.

The blog included an instruction manual for how to stay undercover, emphasising that the Dark Wallet could be used to "send millions of dollars worth of Bitcoin instantly from the United States, United Kingdom, South Africa, Ghana, Malaysia, Sri Lanka, or wherever else, right to the pockets of the Mujahideen".

Amir Taaki believes people should be able to be private about their spending

"It is simple, easy, and we ask Allah to hasten its usage for us," the blog read.

The software allows users to anonymise their Bitcoin transactions.

It involves "trustless mixing" a peer-to-peer technology where a transaction you make will get mixed up with someone else's.

Stained stairs

Although tipped as a future billionaire by Forbes magazine, developer Taaki spends his time living in squats around Europe.

He's currently in a central London squat, which was the centre of G8 protests last year. He points out the stained stairs where the protesters threw red paint bombs at police.

In a sparsely decorated large open-plan room sits a group of Taaki's friends, fellow programmers working on the code and design of the Dark Wallet, along with an open-source journalist and a Bitcoin investor.

Sitting on the floor on one of the cushions is Peter Todd, one of the main developers of Bitcoin.

On the walls is scribbled an address to an old Silk Road site, which has now been shut down.

When questioned Taaki indicates he is comfortable with the possibility of his software being used by extremists in conflicts in Iraq and Syria.

Its apparent popularity with extremists is no concern to the Dark Wallet team

"Yeah, and in fact I shut down my Twitter account because they were shutting down IS accounts.

"I don't think trying to censor information is the way to go."

"You can't stop people using technology because of your personal bias. We stand for free and open systems where anybody can participate, no matter who you are."

Peter Todd agrees.

"I think obviously terrorists will use it and the benefits certainly outweigh the risk.

"Obviously terrorists use the internet, terrorists use freedom of speech and we've accepted that's a trade-off we must make."

Anarchic roots

It's not a view that will sit easily with many people, but these strong libertarian ideals are driving the political side of the Bitcoin movement.

The currency is facing on one side increased calls for regulation from people who want to see Bitcoin become a mainstream payments mechanism and on the other side key developers who are trying to maintain its anarchic roots.

The team behind Dark Wallet live in a London squat

Current attempts at regulation in the United States include the introduction of the Bit Licence in New York - a licence to conduct business using Bitcoin - something that the Dark Wallet developers are fighting back against.

Jamie Bartlett, author of the Dark Net, has spent time with the Dark Wallet developers in their old hacklab in Calafou, Spain.

He said: "The sort of libertarian fringes of the Bitcoin movement are actually incredibly important.

"A lot of those individuals have kept true to the original spirit of Bitcoin which always was actually a political project to try to remove the power over currency and interest rates from central banks."

For the developers of the Dark Wallet, they want their technology to be used in subversive ways, and note it could be more useful than real cash in the hands of a group like IS.

Freedom from scrutiny

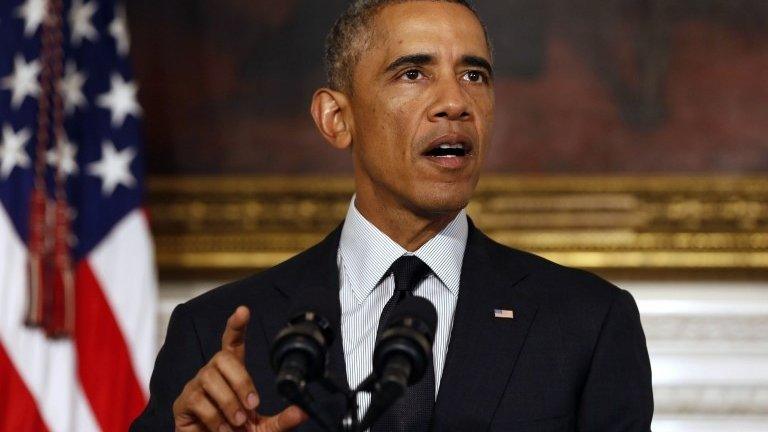

But if transactions of Bitcoin do end up in the hands of IS fighters, it may increase the calls for further regulation from governments.

"If it comes to pass that IS are using Bitcoin or Dark Wallet, any other technology of this type then public concern and public opinion about these technologies will change dramatically," says author Jamie Bartlett.

"Governments will start regulating far harder and public opinion will turn against the programmers as well, so their life could be made far more difficult, especially when they are so open they really don't seem to care who uses their technology.

"This is beyond Bitcoin - these guys are really trying to change the way the whole internet works and there's a chance they can do it."

The Dark Wallet team says it's behind an "ideological movement"

For the Dark Wallet team, freedom from scrutiny comes above all other interests, and fits into what they see as a changing geopolitical landscape.

"Change is something that is inevitable - we're talking about the rise of ideological movements," Taaki says.

"Whether we like it or not we're going to have to deal with this new reality and we have to work with the technology with this new reality."

Watch Jen Copestake's report on BBC Click this weekend on BBC News and BBC World News

- Published28 March 2018

- Published19 September 2014

- Published3 September 2014