Crime-fighting surveillance planes provoke privacy controversy

- Published

WATCH: How US surveillance planes are able to spot murders on the streets

A US company has developed a way to monitor entire neighbourhoods, using a technology originally developed for the recent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. But while police forces are excited by the prospect of getting access to the tech, privacy campaigners see it as a threat to citizens' constitutional rights.

Bang. A shot is fired and someone has been murdered. A victim is found, the police alerted, but the perpetrator has vanished - without being seen.

Such killings happen almost every day in the US - and when no witnesses come forward, it can be hard and very costly to convict the perpetrators.

Now, one company says it has an answer.

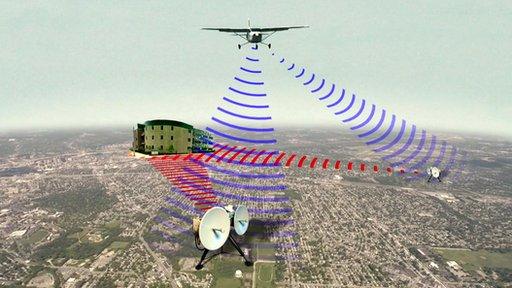

By flying a special manned plane over a city, Persistent Surveillance Systems (PSS) says it is able to view and record everything that is happening on the ground across a 25 sq mile (64.7 sq km) area.

Rigged with 12 high-resolution cameras, a spliced together picture of a sort of "live Google Earth" map is beamed down from the aircraft to analysts.

The PSS named the high-resolution camera system mounted on the plane Hawkeye II

A 600Mbps down link transmits images from the plane to the PSS command centre

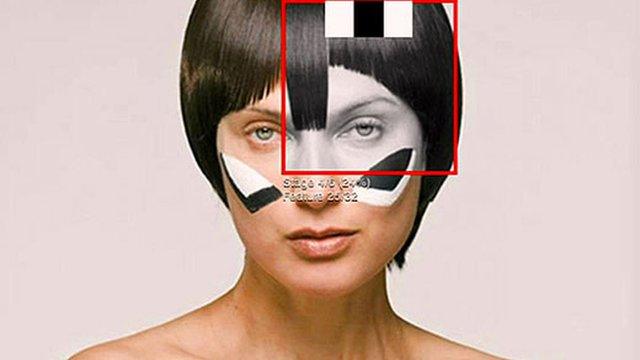

"The resolution is not high enough to show who someone is, people appear as merely one grey pixel on a screen," Ross McNutt, a retired United States Air Force veteran and PSS president, told BBC Click.

But that one pixel is enough for the person's movements to be accurately tracked for the time the plane is in the air - up to six hours.

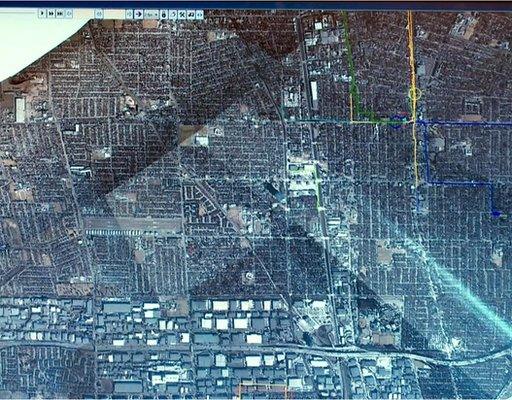

When PSS flew its planes over Compton, California, in early 2012 over nine days, it recorded murders, robberies and many other crimes.

By matching the time frames of the PSS recordings with on-the-ground testimony, analysts and police were able to see the moment when the crime was committed.

They were then able to track where the suspect was before and after the moment of crime, says Mr McNutt.

"It's like opening up a murder mystery in the middle.

"We have actually followed people to multiple murders before," he says.

During testing in areas including Dayton, Ohio, Compton, and Mexico, PSS has witnessed 34 killings.

"Threat to democracy"

But PSS doesn't just see the murders and the criminals - its cameras look down onto the streets and backyards where everyday activities happen as well.

Planes fly thousands of feet above towns, capturing things that escape lenses on the ground

The firm's insistence that the close-ups it obtains are low resolution are not enough to placate opponents who see its tech as a threat to Americans' liberties.

"Not only does the system encroach on people's privacy, tracking the movements of whole communities poses a threat to democracy," says Jennifer Lynch, senior staff attorney with the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

When the police tested the system in Compton in 2012, the public was not informed.

"It is things like this, and the secret monitoring of innocent Muslim students by NYPD in early 2012, that builds mistrust in the police," adds Ms Lynch.

But PSS insists it adheres to a "very strong privacy policy" that imposes tight controls on its analysts.

"We put in place policies and technology that allows us to track where all our analysts have looked," Mr McNutt said.

"We only track people that are involved in crimes, and I can see where my analysts have looked by recording where they have asked [to review] images."

Analysts painstakingly examine the images they receive and log suspects' movements

Racial profiling and targeting minorities is already a worry in places such as Compton where there is a large African-American population - and surveillance increases tensions.

"How do we know what the police would actually be using the surveillance equipment for?" asks Mrs Lynch.

And if people feel like they are being constantly watched, they are less likely to do things that they might not want others to see or hear, she argues.

And that doesn't mean breaking the law.

Going to a gay bar, talking about politics, visiting religious buildings, having more than one relationship - all of these things are legal, but, more often than not, very private.

"Police surveillance concerns could compromise free speech," Ms Lynch says.

"In this way then, people's democratic and constitutional right to act freely within US law is at threat."

Big-brother state

New York City police secretly collected information on Muslim communities in nearby Newark, New Jersey, in 2012

But Mr McNutt says PSS endeavours to address these concerns.

"We have actually gone to the American Civil Liberties Union and said, 'Look, we want your input here,'" he says.

"They don't like what we are doing, [but] they appreciate the fact that we are reaching out and asking for their input."

PSS might be a powerful weapon in fighting crime, but no US police force is currently using its technology on a regular basis.

While tests have been carried out in Baltimore, Philadelphia, and Ohio, in addition to Compton and the Mexican city of Juarez, civil liberties concerns have discouraged officials from signing contracts.

It seems, for now at least, that the rollout of PSS and safer streets it promises are being held in check by the importance Americans place on freedom and privacy.

Watch more clips on the Click website. If you are in the UK, you can watch the whole programme on BBC iPlayer.

- Published27 January 2014

- Published17 January 2014