Bone conduction: Come on feel the noise?

- Published

James Williams of Subpac explains how "bone conduction" is used in his firm's backpack to convey the physical element of sound

Your ears are the best way to listen to sound, but they don't have a monopoly. Two sets of British entrepreneurs want to turn our upper bodies into sound systems.

The voice of BBC Radio 4 veteran broadcaster John Humphrys feels literally guttural - it rumbles deep, with intense bursts, slightly unsettling.

American shock jock Howard Stern isn't physically too shocking at all - more of a persistent purr in your abdomen.

The female voice with its higher frequencies, isn't registering very strongly. But the BBC's Mishal Husain surprises with distinct moments of bass that strike your lower spine.

These are some of my impressions as I try out a Subpac tactile bass system with speech radio. It is a kind of rumble pack that you wear against your back.

Good vibrations

As you listen to sound through headphones as normal, it simultaneously sends vibrations through your body to enhance the experience.

The "audio-tactile loudness illusion" is what researcher Sebastian Merchel, of the Technical University of Dresden, calls this phenomenon.

He has carried out experiments that show people perceive sound to be louder when accompanied by vibrations.

He believes we have overlooked the importance of physical stimulation in recreating musical experiences.

"Just think of hearing - and feeling - a church organ, sitting on a wooden pew," he says.

Google Glass uses bone-conduction technology

"But when concert recordings are played back with hi-fi systems at home, the vibratory information is missing."

It is a method of listening known to scientists as "bone conduction".

Prof Sophie Scott, of University College London, has also been researching this field.

"A lot of sound information in the real world is from vibration, going straight to the cochlea, or inner ear, which processes sound, as opposed to air conduction through our ears," she says.

"This is the same way that a baby listens in the womb."

The technique has been harnessed to allow adults to listen to music underwater, with several companies manufacturing bone-conducting headphones for swimmers.

Wearable technology Google Glass uses a bone-conduction transducer (BCT) resting against the skull as the primary way to convey sound to users.

In these examples, bone conduction offers an alternative to traditional headphones, freeing up the ears.

The Subpac device is being evangelised by a pair of British musicians-turned-businessmen who want it to work in conjunction with headphones as part of an enhanced sound experience.

They want to bring this kind of technology into the mainstream, as a new way to enjoy music.

Their tiny business premises are a garret above a record shop in Soho, London.

Subpac's technology is owned by a Canadian company called Studiofeed

"Inside the Subpac are two transducers," says Steve Snooks, a DJ, "just as you would find in a speaker."

A transducer is in essence a motor for producing controlled vibrations.

"They are wrapped in a special foam," continues his business partner, James Williams. "It resonates at different frequencies, then we also have an algorithm that runs the whole program."

It is no accident that Snooks is a dub DJ. Bass is what Subpac does best, and it is primarily designed for music - he wears it while DJing.

"We hope it will help people appreciate more the quality of music," he says.

"Most music you might stream or download is compressed, cutting out the bass frequencies. This method really comes into its own with vinyl."

Trunk Call

But even with a wide frequency range, the technology has its limits.

You will not always get the experience you want, says Prof Scott.

"You are going to be limited by the acuity of the vibro-tactile system.

"And while it is good at low frequencies, it is less good at high frequencies, so you might want more at the top end, but your sensory systems are limiting that."

So with a dub track you might relish the bass, but in a different genre, such as pop, it might feel unnaturally bass-heavy.

On your bike

Design student Rodrigo Garcia Gonzalez is also interested in the possibilities of audio-tactile loudness illusions - but in a very different way.

He wants to turn your buttocks into a speaker system.

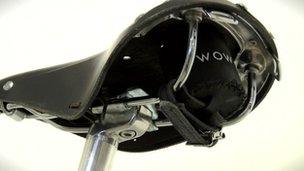

His Wow invention is designed to clip directly underneath a bicycle saddle.

Rodrigo Garcia Gonzalez show how his Wow device works

Like the Subpac, it relies on a transducer. But the electrical signals containing the music are used to send pulses through the bike saddle, which is in direct contact with the rider's posterior, channelling the vibrations through the body to the head.

Again the effect is like an aural hallucination - you are listening to the music, even though it is not passing through the air around you.

Nobody else can hear it the same way. It is slightly disconcerting until you mentally process what is happening.

Whether the sound quality is good enough for it to replace headphones is questionable.

It feels like you are listening to music being played far away in the distance - like a neighbour's loud party.

But the design advantage is clear, says Mr Gonzalez.

A transducer device fits under the saddle

"It's hard to listen to music when you are cycling. You need your ears to know where the cars are."

Mr Gonzalez's invention certainly avoids the inconvenience of getting tangled up in headphone wires.

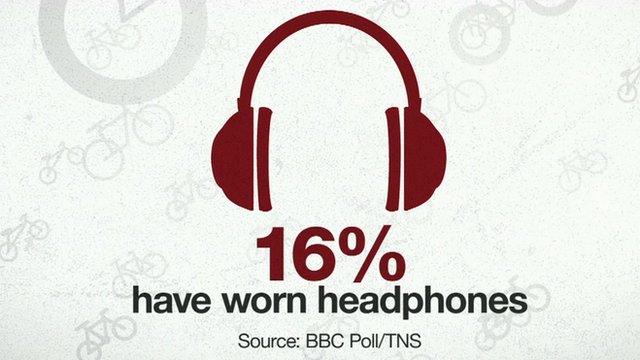

Whether it is safe to be listening to music at all while cycling, is another matter.

Tactile future?

While Mr Gonzalez's invention would find a fairly unique place in the market, the Subpac system already has rivals.

A similar technology with the colourful name Buttkicker, external is already established in America, used by professional musicians to help them play live, and installed in large movie theatres.

And there are already haptic vests specially designed for video gaming.

But as virtual reality and wearable technologies continue their assault on the mainstream, many see tactile sound technology as an area ripe for market growth.

If it remains niche, that market could be just a few cyclists happy with a slightly muffled soundtrack to their daily commute; or a handful of music aficionados wanting to experience that "fuller sound".

However, the market will be a lot bigger than that if more people decide they want to feel the noise.

- Published6 November 2014

- Published7 October 2014

- Published5 November 2014