Outernet aims to provide data to the net unconnected

- Published

Syed Karim outlined his vision for satellite-beamed "libraries" of information

Can an entire library be put in your pocket? Most people would say yes. All you need is a mobile phone with access to the internet.

But what about for the many people in the world that lack internet connectivity? The answer is still yes - at least according to Syed Karim, who explained how at TEDGlobal.

The entrepreneur had been invited to the human ingenuity-themed event in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, to speak about his company, Outernet.

The business aims to address the fact that about two-thirds of the world's population still has no internet access.

"When you talk about the internet, you talk about two main functions - communication and information access," he told the BBC.

"It's the communication part that makes it so expensive."

So, Outernet focuses instead on information. The project aims to create a "core archive" of the world's most valuable knowledge, culled from websites including Wikipedia and Project Gutenberg, a collection of copyright-free e-books. This would be updated on roughly a monthly basis.

Outernet is currently testing a solar-powered receiver that doubles as a wi-fi hotspot

In addition, it would also provide more time-sensitive content - including news bulletins and disaster alerts - that could be updated several times an hour.

All this information would then be broadcast via satellites and picked up by antenna-fitted "receiver" equipment on the ground.

The receivers would in turn create wi-fi links, allowing the data to be copied to individual smartphones and other computers.

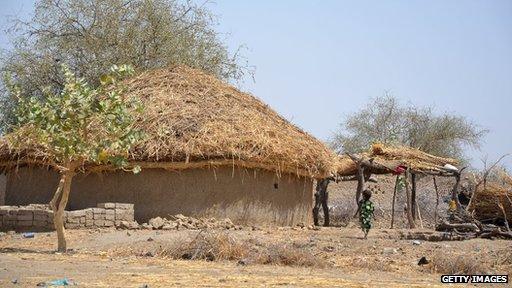

In a small village in central Africa, for example, Mr Karim said, one hotspot with an antenna could provide dozens of books and other information to 300 people living close by.

"If you were in the vicinity of a hotspot receiving the data from the satellite, you would be able to connect with Outernet on your phone and see Librarian - our index software - as if it was just an offline website," he explained.

"There you would find the data, stored in files."

Text requests

Because the Outernet is effectively a one-way connection, it would not provide email or other chat facilities.

But internet-less users would be able to request specific content be added by sending its operators an SMS text message or letter.

Net-connected organisations can, however, pay a fee to have their own material added to broadcasts at specific times, providing a source of revenue.

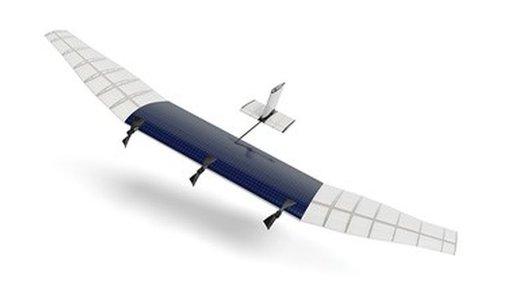

Outernet aims to release branded mobile receivers for its service at a later date

At the moment, the company is using existing audio and video satellites to store and broadcast data.

Mr Karim said the system was currently capable of broadcasting 200MB of data a day, but his intention was to increase that to 100GB or more.

"We want to use as much existing technology and repurpose it a bit, so that people buy as little stuff as possible," he said.

The ultimate idea, however, is to use a constellation of smaller satellites that would be in a lower orbit. Mr Karim said this would allow smaller antennas to pick up the broadcasts, making it possible to offer pocket-sized mobile receivers.

"The first prototype will be a bit fancier, but we can get the price of one of these receivers down to about $20 [£12.40]," he said.

"And at this price, if I'm able to broadcast a dozen e-books a day to anyone in the world, it ends up being extraordinarily powerful," said Mr Karim.

Outernet aims to provide data to villages that lack an internet connection

One expert called the idea "fascinating" - but said the biggest challenge facing Outernet might not be a technical one.

"When you start to think about the needs of rural communities in developing markets, what they are going to be most interested in are things that impact their daily lives - subsistence, crops, weather and healthcare," said Mark Newman from the technology research firm Ovum.

"I question whether by sourcing content centrally and distributing it locally, you will meet those local needs - both in terms of content and language.

"Literacy is also going to be an issue. Delivery by audio rather than text would be something to look at, but that would use up more data."

Race to space

The idea of delivering data to every person on the planet is also high on the agenda of some of the biggest tech firms.

In June 2013, Google started experimenting with Project Loon, which plans to launch a series of balloons that could help people get connected by beaming internet signals down to base stations.

One year later, in north-eastern Brazil, it ran its first test, using Long-Term Evolution (LTE), also known as 4G, to connect a school computer in a rural village to the internet.

And in March 2014, Facebook announced plans to make internet available to regions of the developing world by using drones and an array of low Earth orbiting satellites - much like Karim's plans for Outernet.

Facebook boss Mark Zuckerberg helped create Internet.org, a consortium of companies working towards that very same goal.

Google is funding a rival scheme that aims to create a network of large balloons in the stratosphere that provide internet access to buildings below

Mr Karim believes, however, that broadcasting data offline could be a better way to bypass censorship and to distribute knowledge.

"We are building humanity's public library," he said during his TED talk in Rio.

He also thinks a one-way connection such as Outernet could tackle "information poverty" faster than the other projects.

"Eventually this will be more than likely solved through internet access, but we're talking about something that's 10 or 20 years away," he said.

Even when you had global internet usage rates on a par with those in the US and the UK, said Mr Karim, you would probably still have at least a billion people with no access at all.

"That's the number you should really focus on," he said.

Outernet plans to test its service in South Sudan

Outernet has partnered with the World Bank in South Sudan, where its project will be tested. If all goes according to plan, it could be working as early as July 2015.

The constellation of small satellites though, might become a reality before the network of users.

"This is just going to be a lot easier if we just go ahead and have full global coverage and then wait for people," said Mr Karim.

- Published15 June 2013

- Published28 March 2014

- Published21 August 2013

- Published7 August 2012