Joan Clarke, woman who cracked Enigma cyphers with Alan Turing

- Published

Keira Knightley on Joan Clarke

Joan Clarke's ingenious work as a codebreaker during WW2 saved countless lives, and her talents were formidable enough to command the respect of some of the greatest minds of the 20th Century, despite the sexism of the time.

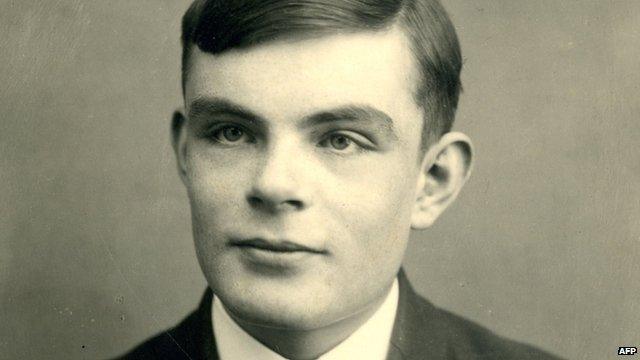

But while Bletchley Park hero Alan Turing - who was punished by a post-war society where homosexuality was illegal and died at 41 - has been treated more kindly by history, the same cannot yet be said for Clarke.

The only woman to work in the nerve centre of the quest to crack German Enigma ciphers, Clarke rose to deputy head of Hut 8, and would be its longest-serving member.

She was also Turing's lifelong friend and confidante and, briefly, his fiancée.

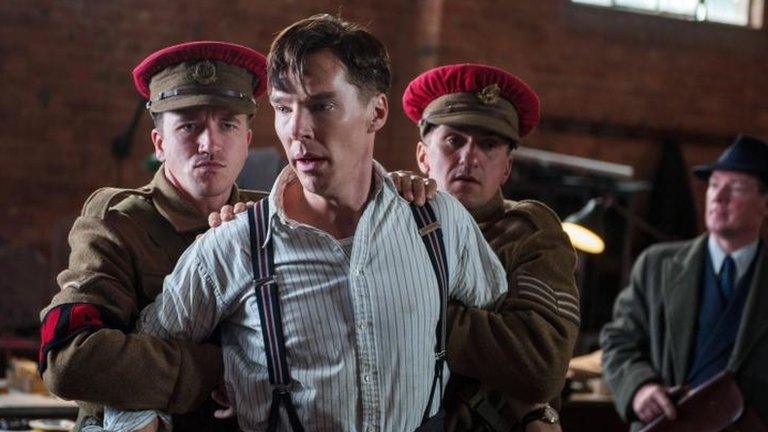

Her story has been immortalised by Keira Knightley in The Imitation Game, out in UK cinemas this week.

Clerical work

In 1939, Clarke was recruited into the Government Code and Cypher School (GCCS) by one of her supervisors at Cambridge, where she gained a double first in mathematics, although she was prevented from receiving a full degree, which women were denied until 1948.

As was typical for girls at Bletchley, (and they were universally referred to as girls, not women) Clarke was initially assigned clerical work, and paid just £2 a week - significantly less than her male counterparts.

Within a few days, however, her abilities shone through, and an extra table was installed for her in the small room within Hut 8 occupied by Turing and a couple of others.

Clarke, played here by Keira Knightly, worked at a time when female cryptanalysts were unheard of.

In order to be paid for her promotion, Clarke needed to be classed as a linguist, as Civil Service bureaucracy had no protocols in place for a senior female cryptanalyst. She would later take great pleasure in filling in forms with the line: "grade: linguist, languages: none".

Lifesaving work

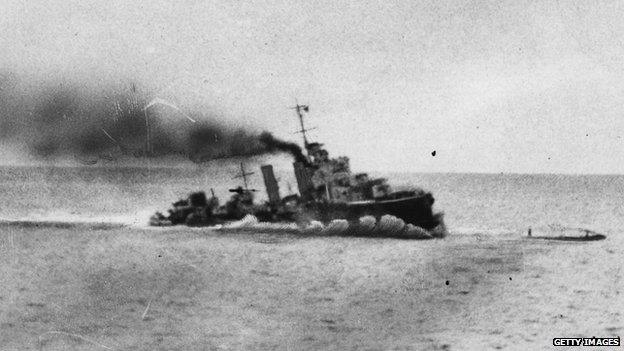

The navy ciphers decoded by Clarke and her colleagues were much harder to break than other German messages, and largely related to U-boats that were hunting down Allied ships carrying troops and supplies from the US to Europe.

Her task was to break these ciphers in real time, one of the most high-pressure jobs at Bletchley, according to Michael Smith, author of several books on the Enigma project.

The messages Clarke decoded would result in some military action being taken almost immediately, Mr Smith explains.

U-boats would then either be sunk or circumnavigated, saving thousands of lives.

Joan Clarke's work helped avert several German U-boat attacks in the Atlantic

Turing 'kissed me'

During this time, Clarke and Turing became ever closer, co-ordinating their days off in order to spend more time together. In 1941, he proposed, although the engagement was ultimately short-lived.

"We did do some things together, perhaps went to the cinema and so on, but certainly, it was a surprise to me when he said... 'Would you consider marrying me?'," Clarke recounted in an interview for a BBC Horizon documentary, aired in 1992.

"But although it was a surprise, I really didn't hesitate in saying yes, and then he knelt by my chair and kissed me, though we didn't have very much physical contact.

"Now next day, I suppose we went for a bit of a walk together, after lunch. He told me that he had this homosexual tendency.

"Naturally, that worried me a bit, because I did know that was something which was almost certainly permanent, but we carried on."

However, just a few months later, Turing broke off the engagement, believing that the marriage would ultimately fail.

We may never hear about the full extent of Clarke's achievements at Bletchley Park

Nonetheless, Clarke and Turing remained close friends until his death in 1954.

Graham Moore, who wrote the screenplay for The Imitation Game, says he saw similarities between the two cryptanalysts, and he believes this brought them together.

"They were both such outsiders, and that gave them some common ground," he explains.

"They were able to see things in a different way to others."

Indeed, they shared each other's passions, such as chess, puzzles, botany and even, on one occasion, knitting.

Forgotten by history

Because of the secrecy that still surrounds events at Bletchley Park, the full extent of Clarke's achievements remains unknown.

Although she was appointed MBE in 1947 for her work during WW2, Clarke, who died in 1996, never sought the spotlight, and rarely contributed to accounts of the Enigma project.

Clarke was the only woman to work alongside Turing (played by Benedict Cumberbatch)

But the esteem in which she was held by her colleagues, and the fact that "her equality with the men was never in question, even in those unenlightened days", as Michael Smith writes, are a tribute to her remarkable abilities.

Morten Tyldum, the director of The Imitation Game emphasises that Clarke succeeded as a female in cryptanalysis at a time "when intelligence wasn't really appreciated in women".

There were a handful of other female codebreakers at Bletchley, notably Margaret Rock, Mavis Lever and Ruth Briggs, but as Kerry Howard - one of the few people to research their roles in GCCS - explains, their contributions are hardly noted anywhere.

"Up until now the main focus has been on the male professors who dominated the top level at Bletchley," she says. In order to find any information on the women involved, you have "to dig much deeper".

"There are a lot of people in this story who should have their place in history," says Keira Knightley.

"Joan is certainly one of them".

The Imitation Game is in cinemas across the UK from 14 Nov

- Published6 June 2014

- Published10 September 2014

- Published8 October 2014

- Published8 January 2014