GCHQ, terrorists, and the internet: What are the issues?

- Published

Does social media aid the march of extremism?

GCHQ boss Robert Hannigan has warned that US technology companies have become the "command and control" network for terrorists.

He wants more action on how such groups use social networks.

He is also unhappy about plans to offer greater encryption for online communications.

So can the uneasy relationship between tech firms and the security services be rebuilt?

What exactly is Mr Hannigan worried about?

His concerns appear to be twofold. Firstly the fact that militant organisations such as Islamic State (IS) are using Twitter, Facebook and WhatsApp to promote themselves and the increasing sophistication that extremists are showing in their use of such platforms.

And secondly he is not happy about pledges from Microsoft, Google, Apple and Yahoo to make encryption a default option to protect users from government snooping.

Tech firms are keen to put user privacy top of the agenda following allegations from former US National Security Agency (NSA) contractor Edward Snowden about mass surveillance in the US and the UK.

How are extremist groups using social media?

The internet is a tool for communication so it should come as little surprise that extremists are using it to recruit, plan campaigns and spread their messages.

But they are becoming increasingly sophisticated in their use of it - recent slick, well-produced videos using hostage British journalist John Cantlie to pass on the IS message provided chilling evidence of how well-versed the modern militant is in using the media.

English-translated bomb-making manuals are freely available online and increasingly terrorists are using chatrooms to openly discuss the best ways to make a bomb.

IS uses popular hashtags to boost the popularity of its material and sends thousands of tweets a day without triggering spam controls.

When social media became a key part of the Arab Spring, one Egyptian activist explained the relationship thus: "We use Facebook to schedule the protests, Twitter to co-ordinate and YouTube to tell the world."

Now it seems that message has become the rallying call for extremist organisations.

If terrorists are communicating openly on Twitter, doesn't that make the security agencies' job easier?

The fact that terrorist organisations now have multiple ways to get their message across means that the drumbeat of terrorism is getting louder and the phrase "anyone can become a terrorist" has never been so relevant.

The problem is summarised by Joseph Kunkle, who works in the office of security technology for the US Department of Homeland Security in a recent article he wrote on the issue, external : "No longer do traditional media control the messages that terrorists seek to deliver. Today instant-messaging jihadists can communicate with anyone... and is increasing the potential for recruiting operatives legally living in targeted countries."

But there is a flipside - having a social-media presence offers law enforcement an unprecedented window onto terrorist activity.

It allows intelligence agencies to determine the identities of supporters and potential recruits. Anyone who follows or befriends terrorist organisations is likely to become of interest to the authorities and, using data analysis, governments can potentially trace entire networks of contacts.

What are internet companies doing to prevent extremist groups using their networks to spread propaganda such as videos of hostages being murdered?

Such videos have horrified the public and become a central propaganda tool for IS.

Google says that it has "zero tolerance" for such videos, but with more than 300 hours of video uploaded to YouTube every minute, it is an impossible job to police content.

Neither is it possible to create an algorithm to censor material before it is uploaded.

Instead, Google relies on the community of users to flag inappropriate content. Such content is then taken down "within hours", according to a spokesman.

And information such as the IP address from which the video was posted is handed over to the authorities when asked for.

Meanwhile, Facebook has been criticised for initially refusing to delete images on the site that showed severed heads in a part of Syria controlled by IS.

It said that the material did not contravene its guidelines but later blocked the material after being contacted by the BBC.

What does GCHQ want tech firms to do differently?

One of its key concerns is the promise from firms such as Google, Apple, Microsoft and Yahoo to use greater encryption in its services.

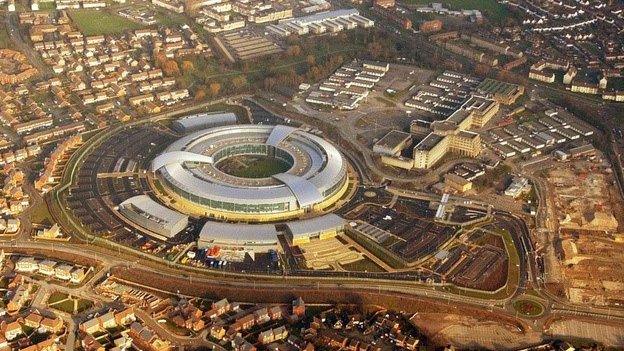

GCHQ thinks greater encryption will make its job harder

If they follow through on these promises, they would be effectively throwing away the key to unlock communications and GCHQ is very keen to persuade them not to go down this route.

As security expert Alan Woodward, who has advised GCHQ in the past, puts it: "If someone encrypts communications, it is difficult to unscramble without the key. The real concern is that the security services will end up blind."

Yahoo has promised "end-to-end" encryption of its mail service by 2015, while Microsoft has pledged to ensure customer content uploaded to its servers would be encrypted by default.

But it isn't entirely clear whether greater encryption will mean that data becomes unreadable.

When Microsoft was asked by the BBC whether this was the case it said it was unable to provide a detailed answer, saying just "it will respond to lawful government requests".

Why are tech firms threatening to make it harder for law enforcement agencies to read communications?

It comes down the the age-old tussle between security and privacy.

Tech firms are acutely aware that the government has a vital role to play in keeping communities safe but it is also aware that its customers - who pay their bills - want greater anonymity and privacy in the post-Snowden world.

While there has been a breakdown in trust between spy agencies and tech firms, most experts believe that the relationship is salvageable.

Data forensics expert Prof Peter Sommer believes we will see more transparency from GCHQ - indeed they may start producing reports similar to the ones that Google and others already publish, which outline how many data requests are made each year and what they are about.

He also predicts that better oversight mechanisms will be put in place to prevent mass surveillance and ensure that any requests for data from tech firms is proportionate and appropriate.

And he thinks that more frank opinions like the ones Mr Hannigan expressed to the Financial Times, external are also likely as GCHQ seeks to reassure the public that it has their best interests at heart.

- Published4 November 2014

- Published8 October 2014

- Published27 August 2014