Ebola-tackling robots to be discussed by the White House

- Published

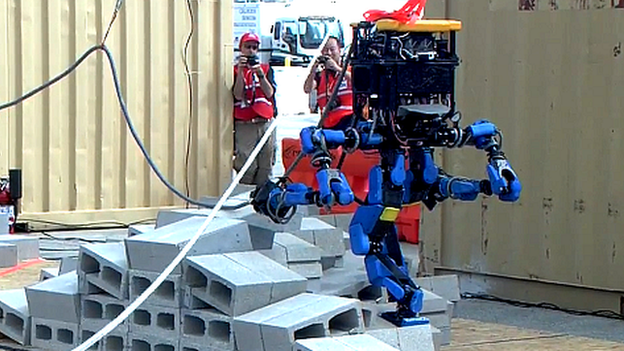

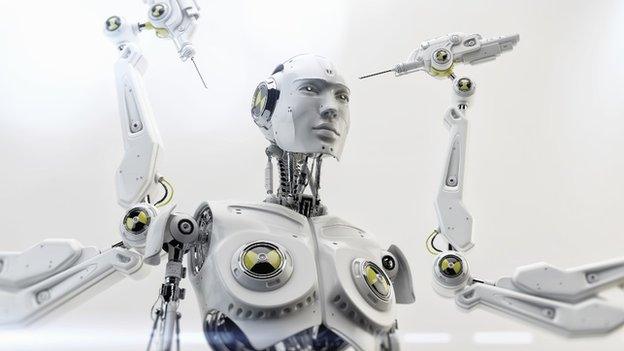

Dmitry Berenson demonstrates how a robot might be able to remove a pair of goggles

Robots have been working in disaster zones since 9/11. They can reach remote and dangerous locations and operate in places people can't go, including the rubble of the Fukushima nuclear power plant.

So it seems a natural step to think about if and where robots could help in a medical crisis like the current Ebola outbreak in West Africa.

It's a topic that will be discussed at a conference later this Friday involving three leading US robotics universities and the White House.

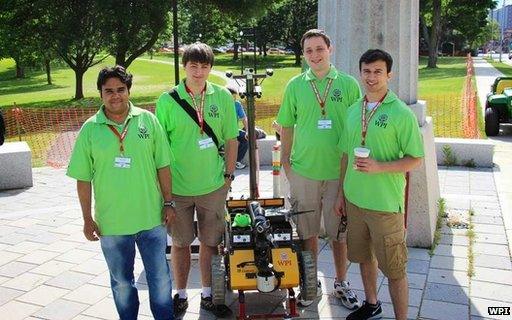

One idea which is being presented by Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI) in Massachusetts is to eschew designing new robots from scratch.

That's because this would be a huge investment of time and money.

Rather, WPI says, existing robots should be repurposed to work on Ebola-specific tasks.

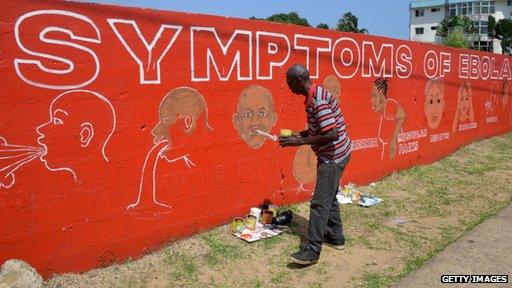

Medical workers put themselves at risk to help tackle Ebola in West Africa

The other universities involved are Texas A&M and the University of California, Berkeley.

Remote-controlled robots

One of the robots WPI has begun adapting is the Aero (Autonomous Exploration Rover).

It was originally designed for space exploration but is now being converted to help with decontamination work by adding sprayer tanks to its body.

The idea is that a person sitting safely outside a contaminated area would control it remotely.

"We're trying to pull the workers further away from the disease," says Velin Dimitrov, a robotics engineering PhD candidate.

The Aero robot was originally designed to take part in a competition held by Nasa

"Ebola doesn't spread through air, so if you can tele-operate a robot from just outside it reduces the risk to the workers."

WPI's team hopes to deploy Aero among other robots to help with the decontamination effort in West Africa within the next three months.

Clothes bots

One challenge is the lack of experience robotics students have with the day-to-day needs of Ebola workers.

So WPI has set up a makeshift tent on its campus to study the safety clothing workers have to wear to avoid the disease.

Researchers are trying to prove Baxter could be used to dispose of contaminated clothes

The university is also looking to repurpose another robot, Baxter. This manufacturing robot was designed to be fixed to one spot in factories, and has the relatively small price tag of $26,000 (£16,392).

The thought is that it could keep health care workers safe by removing their clothing.

WPI is keen to stress that none of the robots involved would work autonomously - each would have a human operator based a safe distance away.

"We're not trying to make this a completely automated process," explains Dmitry Berenson, an assistant professor in WPI's robotics programme.

"The key is you won't need another person to help take the clothing off and you won't need to risk another person being contaminated.

More than 4,800 people have died as a result of the current Ebola outbreak

"This is a point that we keep coming back to: How to keep the human element in the robot interaction?"

Physical presence

Something that the workshop also has to grapple with is the degree to which people with Ebola already feel stigmatised.

Isolating them further by treating them with robots risks causing even greater distress.

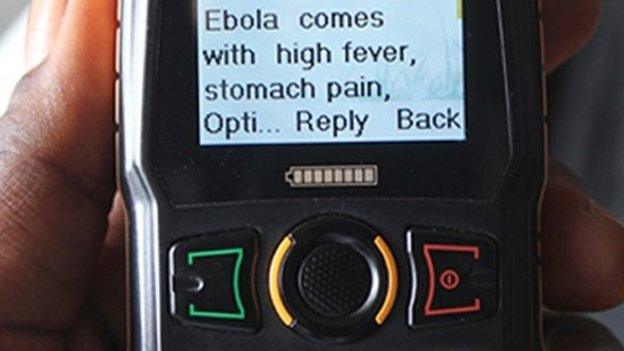

The use of robots for telepresence - which uses a technique to let someone based elsewhere seem as if they are present by showing their face on a screen, using speakers and microphones for conversations, and/or mirroring their body movements - offers a solution.

Robots could provide a cost-effective way to get not only expertise to remote locations, but also to let people interact with loved ones who have been isolated after showing symptoms.

WPI Professor Taskin Padir has also proposed repurposing some field hospital tents to become "tech tents".

These would incorporate sensors used elsewhere to keep watch over elderly patients.

US firm iRobot has already designed a range of telepresence robots for use in hospitals

"A smart tent [would] have networked sensors to provide a mobile robot with reliable navigation. And such a robot can be used to deliver water, food and medicine to the patients and it can be monitored from all over the world," says Prof Padir.

"If I am working in Boston I can still consult with patients.

"The sensors are off-the-shelf devices that we can purchase in stores.

"[They can] detect a door opening or closing, we can even monitor if a person breaks out of isolation."

Mental trauma

The White House workshop will also discuss if people would accept help from robots during an outbreak.

Ebola can spread during the burial process, so the teams want to know if burial robots would be accepted by local communities to transport the deceased.

Transporting the bodies of Ebola victims after death can present a risk of contagion

"There are definitely benefits to technology where we don't want to put human life in danger, but with that comes risks," says Jeanine Skorinko, associate professor of psychology at WPI.

The danger, she explains, is that the desire to secure medical workers' physical safety has the side-effect of causing the patients and their families additional mental trauma.

Flying robots

Commercial robot companies are also getting involved.

Helen Greiner is chief executive of CyPhy Works, which specialises in tethered drones.

Its products include Parc (persistent aerial reconnaissance and communications), a drone that can carry out round-the-clock surveillance from the sky if its tether is connected to a power source below.

She suggests that Parc's tether could also be used to send video and audio to and from isolated victims.

Helen Greiner's company CyPhy Works makes tethered drones which can survey an area 24 hours a day, seven days a week

"The Parc system with the tether is very good for building a cellular network," she adds.

"If there was no way to have good communications, you could send this up with a small cellular box in it.

"It's flying up at 500ft [152m], so you don't have to bring in the infrastructure or build a tower to turn it on" she says.

Ms Grenier says she is not worried about the robots being accepted.

"If they are bringing you something that you want or need, if they're bring clothing and stuff, I think people will be very excited."

Watch more clips on the Click website. If you are in the UK, you can watch the whole programme on BBC iPlayer.

- Published27 October 2014

- Published14 October 2014

- Published30 June 2014

- Published23 December 2013