Will workplace robots cost more jobs than they create?

- Published

Some experts fear robots could destroy more jobs than they create, causing problems for future generations

The UK is set to unveil its robotics strategy on Tuesday, revealing a plan drawn up by the Technology Strategy Board that aims to spur the country on towards capturing a significant slice of what is predicted to become a multi-trillion pound industry.

From self-driving cars to robotic postal deliveries, from carebots for elderly people to surgical snakes, the sector promises riches for the companies that design and engineer the bestselling automatons.

But what happens to the staff whose tasks they take on? Does the new technology help them work more efficiently, or does it put their livelihoods at risk?

It is a bone of contention between academics, with some convinced that offloading work on to machines will worsen unemployment, while others believe it will boost prosperity.

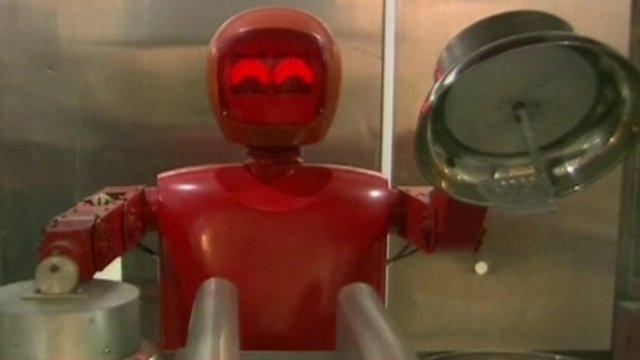

John Maguire meets Bob, the robotic security guard

Take Bob for example. A robot security guard that patrols the workplace, scanning rooms in 3D and reporting any anomalies.

It's the brainchild of scientists at the University of Birmingham, who insist the machine will "support humans and augment their capabilities", despite concerns that such a technology could eventually replace human security officers.

The US army, meanwhile, is reported to be considering, external replacing thousands of soldiers with remote-controlled vehicles as it tries to manage sweeping troop cuts.

Rise of the robots

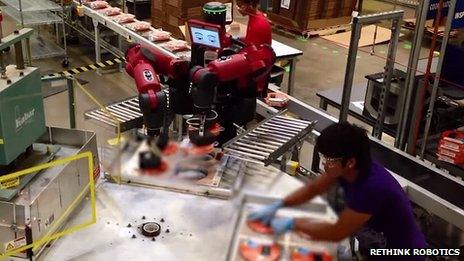

The Baxter robot is designed to work with humans on production lines

Dr Carl Frey, an Oxford University researcher who has written detailed studies on the rise of computerised labour, made headlines when he predicted that work automation, external put up to 47% of existing US jobs at "high risk".

His forecast was attacked as being a "major overestimate" by Prof Robert Atkinson, president of the US-based Information Technology and Innovation Foundation think tank.

But Prof Frey stands by his prediction insisting that the number should not be seen as "shocking" bearing in mind the process could take a couple of decades.

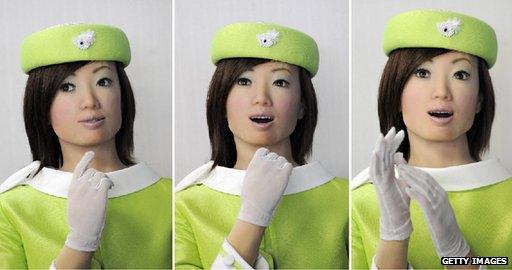

Japanese robot maker Kokoro has created a robot receptionist for offices

While the two men might remain at odds about the size of the figure, they do agree that more machines are coming to the workplace.

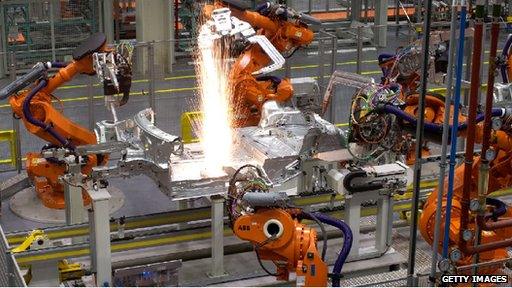

Last year, the number of industrial robots sold globally hit a record high of 179,000, according to the International Federation of Robotics.

Germany, Japan and the United States have become prolific investors in automated technology, but even in nations where low-wage factory work is common, there are clear signs of machine adoption.

President Obama has said that robots could increase the productivity of workers in the manufacturing sector

China, for example, last year became the world's largest buyer of industrial robots. And according to Dr Frey, machines are finding their way into India too.

"Nissan relies on industrial robots to produce its cars in Japan," he says, "but we're already seeing examples of the same type of businesses in India becoming automated."

Companies across the world are investing in new technologies that could automate a whole range of jobs.

In Germany, for example, the robotics firm Kuka is testing an unmanned TV camera for live broadcast that promises to offer "smooth, shake-free camera pan". The BBC already uses a different robotic camera system in its studios.

Meanwhile in Japan, the robotics manufacturer Yaskawa has produced a dual-arm robot that can assemble goods on production lines with human-like dexterity.

Foxconn, a China-based assembler of iPhones which employs more than a million people, has told the BBC it is investing in automation technologies to help soak up its intense workload.

The car industry was one of the early adopters of robotic technologies

But it's not just physical machines that are on the rise - software "bots" are also reshaping the workplace.

In March, the Los Angeles Times automatically published, external a breaking news story thanks to an algorithm that generates a short article when an earthquake occurs.

Yaskawa makes a dual-arm robot that assembles production line goods with human-like dexterity

And cab service Uber is able to undercut rivals in part because its software automatically matches empty cars with passengers, doing away with the need for human dispatch operators.

Uber's boss Travis Kalanick has indicated he will eventually, external be able to cut costs even further when he eventually replaces the fleet with driverless vehicles.

Jobs 'at risk'

Dr Frey says such major new technological developments will only accelerate over the coming years.

His 2013 study found that, from a sample of 702 occupations, nearly half were at risk of being computerised.

Some jobs, such as being a dentist, are dependent on advanced detection skills and thus less likely to be replaced by a machine. Equally "safe" are sports trainers, actors, social workers, firefighters and, most obviously, priests.

But typists, estate agents and retail workers are among occupations deemed highly likely to be automated in the future, he claims.

Kuka has developed a television camera that promises "shake-free" pans

"I was somewhat surprised when we arrived at that 47%," he tells the BBC.

"But the lines between man and machine are becoming increasingly blurred. We are seeing some jobs automated already, but not to the extent that we believe they will be over the next few decades."

Boom years

Robots replaced human jockeys in a recent camel race in Dubai

Prof Atkinson observes there is "a genuine fear that we're going to automate so much work that there will be nothing left for people to do", but believes such concerns are overblown.

"Our internal estimates are, at best, a third of current jobs reasonably could be automated with existing technology.

"But one of the mistakes people make in this line of theory is they don't differentiate between functions and jobs.

"A machine can do a certain function, but most people's jobs involve multiple different functions. You can't automate all of those tasks with a single machine."

He adds that automation will only improve people's livelihoods: "My argument is that when a company saves costs, its extra revenue will inevitably feed back into the shareholders and employees. That increases consumer spending and creates more jobs."

Prof Frey agrees that such a utopian scenario is possible, but companies must plan ahead to achieve it.

"The past 20 years have taught us that some places have adapted well to the computer revolution and some haven't.

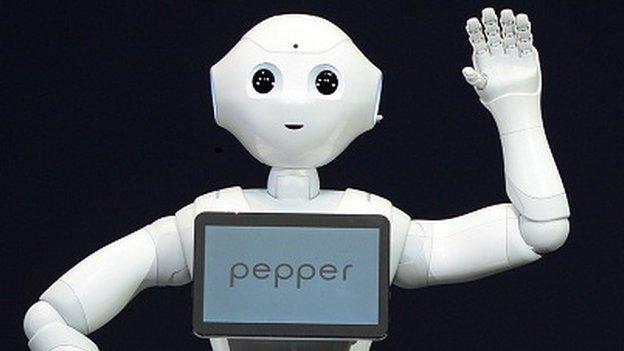

Mobile network Softbank has deployed its Pepper robots to greet customers at its Japanese stores

"Many studies have shown how computers have replaced labour in many of the old manufacturing cities, but at the same time, these computers have created a whole host of occupations elsewhere.

"Some thrive with new changes and others don't. It all depends on how you adapt."

- Published25 June 2014

- Published5 June 2014

- Published13 May 2014

- Published7 May 2014

- Published22 April 2014

- Published9 April 2014