Facebook hosted Lee Rigby death chat ahead of soldier's murder

- Published

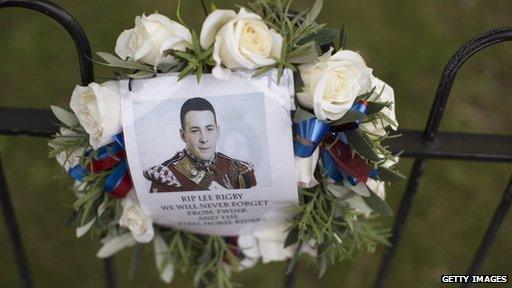

Fusilier Lee Rigby was murdered in London on 22 May last year

Facebook was the firm that hosted a conversation by one of Fusilier Lee Rigby's killers five months ahead of the attack, the BBC has learned.

Michael Adebowale said he wanted to kill a soldier and discussed his plans in "the most graphic and emotive manner", according to the UK's Intelligence and Security Committee.

The ISC said the social network did not appear to believe it had an obligation to identify such exchanges.

Facebook said it does tackle extremism.

"Like everyone else, we were horrified by the vicious murder of Fusilier Lee Rigby," said a spokeswoman.

"We don't comment on individual cases but Facebook's policies are clear, we do not allow terrorist content on the site and take steps to prevent people from using our service for these purposes."

The ISC's report said, however, that the company should do more.

"Had MI5 had access to this exchange, their investigation into Adebowale would have become a top priority," it stated.

"It is difficult to speculate on the outcome but there is a significant possibility that MI5 would then have been able to prevent the attack."

Facebook said it was horrified by Fusilier Lee Rigby's murder

The ISC does not identify Facebook as the host service in the edition of its report released to the public, but the BBC understands it does do so in the complete version given to the Prime Minister.

In it, the committee states that the company's failure to notify the authorities about such conversations risked making it a "safe haven for terrorists to communicate within".

It highlights that the UK's security agencies say they face "considerable difficulty" accessing content from Facebook and five other US tech firms: Apple, Google, Microsoft, Twitter and Yahoo.

The companies in question have said in the past that they have a duty to protect their members' privacy.

"If the government believes that it needs additional powers to be able to access communication data it must be clear about exactly what those powers are and consult widely on them before putting proposals before Parliament," said Antony Walker, deputy chief executive at TechUK, a lobbying body that works with Facebook.

Automated checks

The ISC's report identifies a "substantial" online exchange during December 2012 between Adebowale and a foreign-based extremist - referred to as Foxtrot - who had links to the Yemen-based terror group AQAP, but was not known to UK agencies at the time.

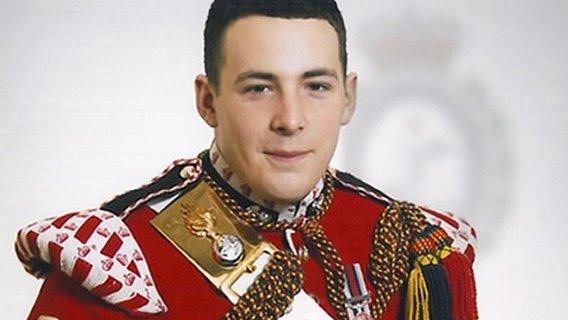

Michael Adebowale has been jailed for a minimum of 45 years

Foxtrot is reported to have suggested several possible ways of killing a soldier, including the use of a knife.

After the murder of Lee Rigby an unidentified third-party provided a transcript of the conversation to GCHQ.

The information was also said to have revealed that Facebook had disabled seven of Adebowale's accounts ahead of the killing, five of which had been flagged for links with terrorism.

This had been the result of an automated process, according to GCHQ, and no person at the company ever manually reviewed the contents of the accounts or passed on the material for the authorities to check.

GCHQ notes that the account that contained the phrase "Let's kill a soldier" was not one of those closed by Facebook's software.

The agency added that the social network had not provided a detailed explanation of how its safety system worked.

ISC said that among the information Facebook did disclose was the fact it enabled users to report "offensive or threatening content" and that it prioritised the "most serious reports".

However, the committee reflected that such checks were unlikely to help uncover communications between terrorists.

It acknowledged that in some other cases, Facebook had indeed passed on information to the authorities about accounts closed because of links to terrorism. However, it said the failure to do so after deactivating Adebowale's account had been a missed opportunity to prevent Lee Rigby's death.

"Companies should accept they have a responsibility to notify the relevant authorities when an automatic trigger indicating terrorism is activated and allow the authorities, whether US or UK, to take the next step," its report concluded.

"We further note that several of the companies attributed the lack of monitoring to the need to protect their users' privacy. However, where there is a possibility that a terrorist atrocity is being planned, that argument should not be allowed to prevail."

But one digital rights campaign group has taken issue with these recommendations.

"The government should not use the appalling murder of Fusilier Rigby as an excuse to justify the further surveillance and monitoring of the entire UK population," said Jim Killock, executive director of the Open Rights Group.

"The committee is particularly misleading when it implies that US companies do not co-operate, and it is quite extraordinary to demand that companies pro-actively monitor email content for suspicious material.

"Internet companies cannot and must not become an arm of the surveillance state."

- Published25 November 2014

- Published25 November 2014

- Published25 November 2014