Syntax era: Sir Clive Sinclair's ZX Spectrum revolution

- Published

Sir Clive Sinclair on personal computing

Sir Clive Sinclair appears pretty laid back about concerns that he may have hastened the demise of the human race.

His ZX Spectrum computers were in large part responsible for creating a generation of programmers back in the 1980s, when the machines and their clones became best-sellers in the UK, Russia, and elsewhere.

At the time, he forecast that software run on silicon was destined to end "the long monopoly", external of carbon-based organisms being the most intelligent life on Earth.

So it seemed worth asking him what he made of Prof Stephen Hawking's recent warning that artificial intelligence could spell the end of the human race.

"Once you start to make machines that are rivalling and surpassing humans with intelligence it's going to be very difficult for us to survive - I agree with him entirely," Sir Clive remarks.

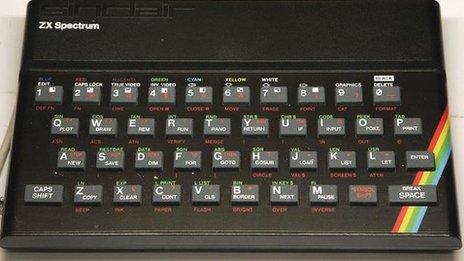

Sir Clive's ZX Spectrum computers inspired thousands of people to learn to programme

"I don't necessarily think it's a bad thing. It's just an inevitability."

So, should the human race start taking precautions?

"I don't think there's much they can do," he responds. "But it's not imminent and I can't go round worrying about it."

It marks a somewhat more relaxed view than his 1984 prediction that it would be "decades, not centuries" in which computers "capable of their own design" would rise.

"In principle, it could be stopped," he warned at the time. "There will be those who try, but it will happen nonetheless. The lid of Pandora's box is starting to open."

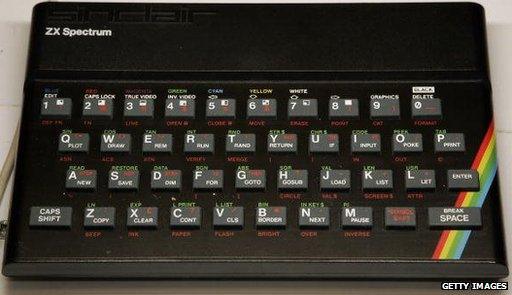

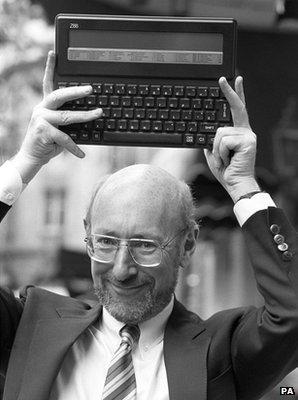

Sir Clive was the most famous figure in the UK's computing sector in the 1980s

The reason, he says, is that we are not using advances in computing power to their full potential.

"I think progress is not that fast.

"Just look at what the machines do. They're not doing much more than what they were."

Cut-price computers

Of course, Sir Clive's computers have already given many of us a taste for "death-by-computer".

Crash Magazine described Atic Atac's graphics as being "just marvellous" giving them a 95% score in 1983

Many of today's forty-somethings lost one life after another as they struggled to complete Spectrum games such as Atic Atac, Jet Set Willy and Manic Miner.

But while such titles are remembered with fondness, it's easy to forget that back in 1982 Sir Clive was taken seriously when he claimed his technology, external was set to surpass IBM's PC platform to become the dominant force in home computing.

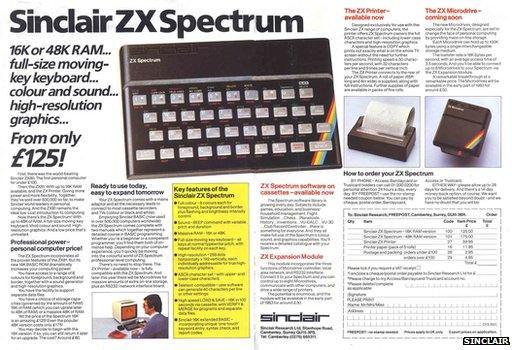

"Home computers were a fairly new thing but they were extremely expensive and what we managed to do was to bring them way down in price - about the £100 bracket," he recalls.

"We had to come up with a huge number of the innovations to get the price bracket where we wanted it... new architecture, new programs, just about everything was fresh."

Sir Clive had already enjoyed success with the ZX80 and ZX81 computers, but it was the Spectrum that really became a phenomenon.

The original adverts for the ZX Spectrum placed strong emphasis on its price

The original models had as little as 16 kilobytes of Ram memory and took five minutes or more to load programs from a cassette, but they changed lives.

"Before Sir Clive's products, home computers were kits of parts with a couple of LEDs and a numeric keypad," recalls Mike Talbot, creator of dozens of other games.

"The ZX series brought computers out of the lab and made them a book-sized resident of the bedroom and study.

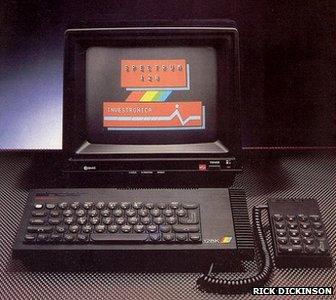

The Spectrum ran more than just video games, even though that is what most people bought it for

"The key was programmability. Computers suddenly offered an endless series of possibilities, limited only by imagination and the ability to grasp and master the technical details.

"It was a pivotal moment for so many in the tech industry and sparked the subsequent decades of tech entrepreneurs, start-ups and innovative thinking that have fundamentally changed the industry. The fact it happened in Britain has made this country one of the tech leaders of the world."

'Dead flesh'

Even so, the models had their quirks. Their graphics suffered from colour clash - where one colour would bleed into another when objects came into contact.

And some critics described the rubber keys found on the early models as resembling "dead flesh".

"They were unusual," acknowledges Sir Clive. "It was all moulded in one piece of rubber.

"It was very cost-effective but a little bit strange. But the customers didn't seem to mind."

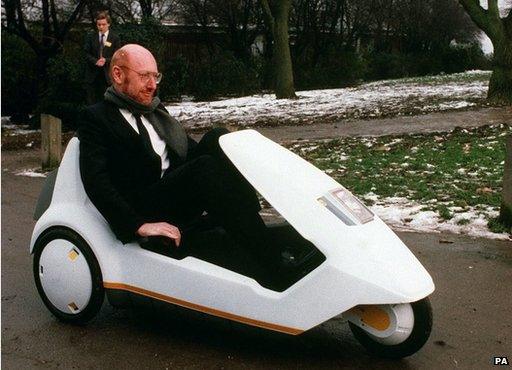

Sinclair Research did not carry out market research into the C5 before funding the manufacture of the electric vehicle

A games computer crash caused by shops overstocking the products, lacklustre demand for the business-focused Sinclair QL computer and Sinclair Research's misadventure with the ill-fated C5 electric vehicle all contributed to the downfall of the Spectrum.

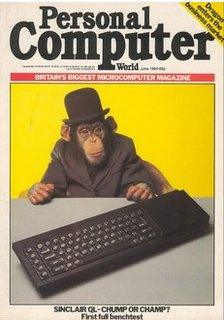

The Sinclair QL - which stood for quantum leap - struggled to attract business software developers

In 1986 the cash-strapped firm sold the range to Alan Sugar's Amstrad, which subsequently added built-in tape players and disk drives to the machines but never did much to develop the underlying computer technology before abandoning the platform altogether in 1992.

Even if different choices had been taken, Sir Clive now acknowledges the Spectrum never had a real chance of beating the PCs of the time.

"Their computer designs were abominable by our standards," he says.

"But because they were IBM they became the standard.

"IBM had such a powerful position, I don't think we could have challenged it."

Spectrum reborn

Sir Clive went on to develop other computers, attempting to popularise the idea of laptops, first with the Z88 and then the never-released Pandora, before giving up on the field altogether.

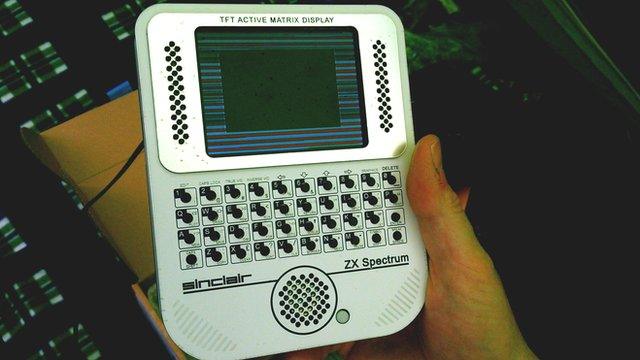

But he has returned to the public eye thanks to a successful crowdfunding campaign to create the Spectrum Vega, a budget computer that promises to come pre-installed with hundreds of the original 48K and 128K Spectrum games.

"It's a means of getting the games back into the public domain," Sir Clive explains.

Sir Clive owns a stake in the company making the Spectrum Vega computer

The machine lacks a physical keyboard, so it's not suited for programming.

That might seem a shame - arguably Sir Clive's legacy is that he jumpstarted coding as a hobby - but, as he notes, the Raspberry Pi already fills what had become a gap in the market.

"It's very exciting. I think it's dramatic and terribly clever," he says.

Sir Clive Sinclair's Z88 laptop failed to match the success of his earlier ZX-series computers

"The price point is just fantastic, and so suddenly people can again get their hands on computing power and play with it, manipulate it and really understand it."

C5 successor

Despite his apparent untarnished enthusiasm, it is somewhat startling to learn Sir Clive doesn't use email, the web or even own a computer.

"I don't like distraction," he says.

"My wife is very much connected to the web so if I need to do anything through that she very kindly orders it for me."

He prefers, he explains, to dedicate his time to electric vehicles, saying he is working on a "very radical" bicycle set to shake up the market.

He has, of course, made similar claims before with the C5 and later the motor-enhanced Zike.

Might it not be better to return to computing and apply his considerable intellect to the sector in which he has had most success?

"Well, maybe I'll get back to it, yes," he says, not totally convincingly. "Perhaps."

- Published2 December 2014

.jpg)

- Published12 September 2014

- Published23 April 2012