New projects bring early computers back to life

- Published

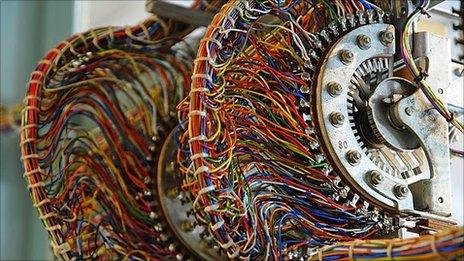

Restoring old computers can be a fiddly, time-consuming task

How many bits are there in a byte? Eight, right?

Well, it depends. While nowadays it is widely accepted that there are eight bits in a byte the bit-count in that computing fact was not always so settled.

In the early days of computers there was little consensus about the basic computational units used to crunch numbers in those older, hulking machines.

"Everyone thinks a byte is eight bits but that's a relatively new development," said Dr Doron Swade, founder of the Computer Conservation Society (CCS) that has now been going for 25 years.

The society is helping to unearth the history of computers, recording how they were built and how those now standard units came about.

"What's astounding is how different they all were," he said, adding that the basic numerical systems seen in those old machines were very different. Some machines were decimal, others binary and others used octal or hexadecimal schemes.

Before eight-bits-to-a-byte became standard, a byte could have four, six or even seven bits depending on the machine.

Restoring the IBM 1401

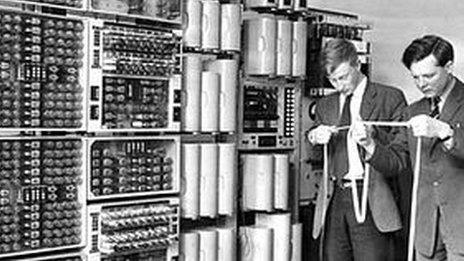

Over the past 10 years, Robert Garner has led a project at the Computer History Museum in California to bring ageing IBM 1401 machines back to life.

The 1401 was a hugely influential machine, says Mr Garner, and was the most widely used computer in the 1960s.

"Back then one in every two computers was a 1401," he said. Old IBM engineers drew on their knowledge to restore the machines and now they form an interactive experience at the museum used to teach people about the early days of IT.

"When they come in the lab and see it for the first time it's a shock," said Mr Garner. "It's really a bit of a dinosaur."

Many CCS members are involved in projects to resurrect old machines and, in so doing, gain valuable knowledge.

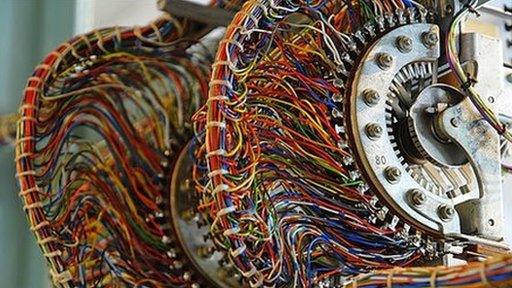

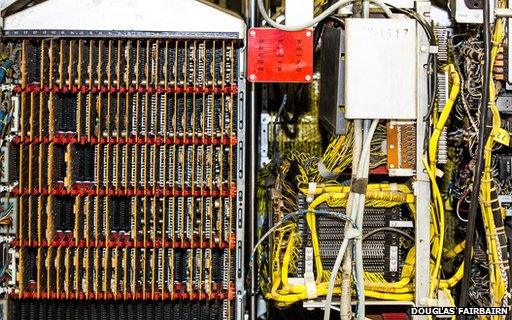

"What it is we learn by reconstruction of machines is irreplaceable," he said. "The level of detail we get, what circuits were used, if a wire goes from pin one to pin seven, that's where reconstruction enters into history.

Restoring the IBM 1401 involved finding lots of components to fix system boards

"We are creating history from materials of those periods."

The work is needed because in the early days of the computer industry little was standard. Almost every machine was made by a different company and all found different ways to process data.

None of them shared information about the innards of their machines.

In some respects, those days of pioneering computer engineering had a lot in common with a much earlier age, Dr Swade told the BBC.

"It was like 19th century mechanical workshops in that it was before standardisation," he said.

In many of those early computers that people are restoring, circuit diagrams have been lost and those that exist are only the schematics created when a computer was on the drawing board.

The machine seen on those blueprints is often very different to the one that left the manufacturing plant.

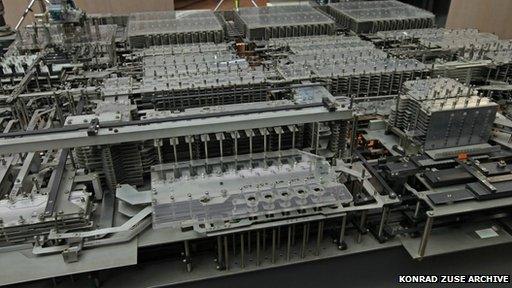

The Z1 is an entirely mechanical machine with thousands of moving parts

The good news, he said, is that the entire history of the computer industry has taken place within living memory. This means that, with a few exceptions, there are people alive who worked with every computer ever built.

When documents are missing or misleading, talking to the old engineers who worked on the machines at the time is invaluable.

"When pioneers are put in front of machines they used to work on, that unlocks memories you would not get just talking to them across a table," said Dr Swade.

"We get to find out to what extent the documentation conform[s] to the machine.

"And for reconstruction purposes it is important to talk to the people involved. Anyone with technical knowledge is invaluable."

When computers were mechanical

The Zuse Z1 was made by engineer Konrad Zuse in the late 1930s and was entirely mechanical.

The original Z1 was destroyed in a bombing raid against Berlin during World War Two but was re-created in the 1970s and 80s by Mr Zuse and put on display in the German capital.

However, the recreated machine is too fragile and unreliable to be used regularly.

This has prompted Prof Raul Rojas and colleagues to make a virtual version so others can see how the machine works.

"It was very difficult to put everything together because although we have the blueprints they have modifications written on them," he said.

"There are modifications written in red, green and blue pencil and only he knew which he wrote last and we don't," he said.

"It has 20,000 logical elements in it and they are all mechanical. There are no cables transmitting information. It's a machine that Charles Babbage would have been proud of."

Evidence for the growing interest in restoring old computers can be seen in the growing number of entries for the annual Tony Sale Award.

This was created in memory of Tony Sale - one of CCS's founding members who died in 2013 and led many IT resurrection projects.

Most famously Mr Sale spent 14 years recreating the Colossus computer that cracked codes for the Allies during WW2.

In 2014, two projects won the Tony Sale award - one brought two IBM 1401 machines back to life and another has done valuable work on the German Z1 computer.

"There's no doubt that from the supply side this activity is growing," said Dr Swade. "And no museum disputes the huge social value of having these machines on display."

- Published5 February 2014

- Published8 May 2012

- Published26 November 2014

- Published20 November 2012