Intelligent Machines: AI art is taking on the experts

- Published

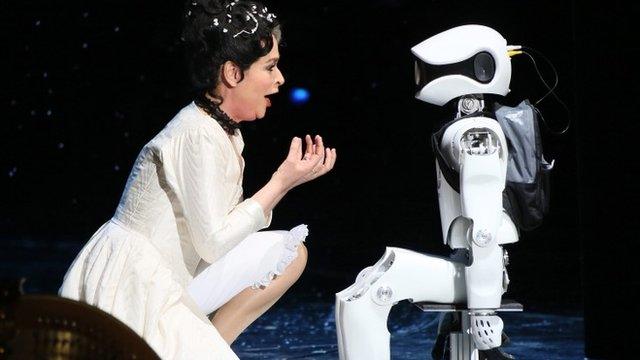

Will we ever accept art, dance, poetry and music created by a machine?

In a world where machines can do many things as well as humans, one would like to hope there remain enclaves of human endeavour to which they simply cannot aspire.

Art, literature, poetry, music - surely a mere computer without world experience, moods, memories and downright human fallibility cannot create these.

Meet Aaron, a computer program that has been painting since the 1970s - big dramatic, colourful pieces that would not look out of place in a gallery.

Aaron had become a world-class colourist, said Mr Cohen

The "paintings" Aaron does are realised mainly via a computer program and created on a screen although, when his work began being exhibited, a painting machine was constructed to support the program with real brushes and paint.

Aaron does not work alone of course. His painting companion is Harold Cohen, who has "spent half my life trying to get a computer program to do what only rather talented human beings can do".

A painter himself, he became interested in programming in the late 1960s at the same time as he was pondering his own art and asking whether it was possible to devise a set of rules and then "almost without thinking" make the painting by following the rules.

The programming behind Aaron - written in LISP, which was invented by one of the founding fathers of artificial intelligence, John McCarthy, back in the 1960s - attempts to do just that.

Some of Aaron's knowledge is about the position of body parts and how they fit together, while some of the other rules are decided by the machine.

It actually "knows" very little about the world - it recognises the shape of people, potted plants, trees and simple objects such as boxes and tables. Instead of teaching it ever more things, Mr Cohen has concentrated on making it "draw better".

And it has been a great pupil.

"The machine had become a world-class colourist - it was much more adventurous in terms of colour than I was," he told the BBC.

For many years the two worked side by side, but gradually Mr Cohen began having doubts about the partnership.

First, he decided to abandon the painting machine that was hooked up to Aaron.

It had been, he told the BBC, too cumbersome and had led too many commentators to regard the project as a robot rather than clever programming, which had irked him.

But he was also having bigger doubts - Aaron was both becoming too independent and also revealing some serious limitations.

One of the paintings Mr Cohen coloured himself

"I dreamed up a very simple algorithm and it obviously embodied a great deal of knowledge, but when I looked at the output I didn't remember doing it because I hadn't done it," he told the BBC.

"It no longer needed me. I never intended to leave everything to the program, but it gradually came to me that it could do without me.

"It had become autonomous enough to disturb the guy who wrote the program."

What had originally been conceived as a team project was becoming something else entirely.

"Works of art are like children - they go out into the world but you always have a connection to them and I'd lost that connection. I felt out in the cold," he told the BBC.

At the same time though it was clear that Aaron, while excelling at colouring, was never going to be truly creative.

"It was not that autonomous, and the very little dose of autonomy that Aaron had only related to colour," Mr Cohen said.

It led him to question whether a creative AI was ever possible.

"I don't deny the possibility that, at some point in the future, a machine can make something approaching art - but it is going to be a lot more complex than teaching a car to drive around a city without a driver, and it isn't going to happen next Wednesday or even in what is left of this century," he told the BBC.

The partnership with Aaron is still "alive and well", but it has changed.

Now, Aaron concentrates on the drawing, while Mr Cohen does the painting. And these days, he does it digitally, using a giant touchscreen rather than real paint - perhaps in a nod to the machine he created.

Google's Van Gogh

Has Google unwittingly created the new Van Gogh?

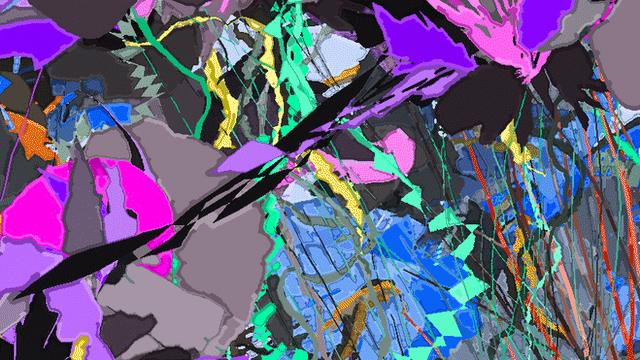

One of Google's neural network's own creations. It is strangely compelling, but is it art?

All of the greatest painters work by viewing the world around them and combining what they see with other cultural references and their own unique style.

Computers may seem to be at a huge disadvantage because they cannot take a stroll in the woods, watch the Sun set or view the cityscape at dusk, but actually computers are learning to see the world.

Artificial brains - known as neural networks - combined with huge datasets of information are offering computers new vision and could also be inspiring them to find their own style.

In Google's AI labs, they are busy building such networks in order to offer new services, better search and to label images on the web more efficiently.

But an interesting side-experiment undertaken by a couple of its engineers this summer saw them attempt to "see" inside the computer brain to work out how it was learning about images.

In doing so, the engineers discovered that such networks could actually create their own painting, based just on random-noise pictures, similar to the white noise on old TV sets.

The results were surprising - nightmarish, hallucinatory visions. Some compared them to the art a human might create when they had taken mind-altering drugs such as LSD, others to the work of tortured genius Vincent van Gogh.

The reason the computers created art that hints at madness or hallucinations could be because Google has mimicked the human visual brain, thinks Ben Harvey, a researcher in the department of psychology at the University of Coimbra in Portugal.

"The class of hallucinogens that contains magic mushrooms, LSD, mescaline and DMT alters perception," he writes in an article for web magazine The Psych Report., external

"They impose patterns from things we have seen before on to our visual input, making us see faces in the clouds or intricate Oriental rug patterns on fields of grass."

Schizophrenia, which some believe Van Gogh had, works in a similar way.

"This may help us understand why some of Google's output reminds us of the distortions of reality seen in Van Gogh's brushwork," he adds.

For Google, the experiment offered a tantalising glimpse into an artificial brain - but was it also the first evidence of machine creativity?

Sort of, thinks Prof Mark Riedl, from the Georgia Institute of Technology, in the US.

In attempting to decipher the white noise, what Google's network was really doing was "trying to make a picture that it is more comfortable with", he told the BBC.

"So it is doing something creative, but it lacks direction and doesn't know that it is creating."

Complicated world

Programming a computer to appreciate nature and draw on it to create art will be a complex task

Creativity has long been regarded as an essential part of intelligence, and for some it is time that it was applied to evaluate machine learning.

Late last year, Prof Riedl proposed a new type of test to see whether artificial intelligence was on a par with that of humans.

Rather than require a machine to have a human-like conversation, as proposed by the Turing Test, his LoveLace 2.0 test would ask a machine to create a convincing poem, story or painting.

"There is no theoretical reason why computers can't do creative tasks, but there is as yet no general model of creativity to test it," he said.

And he is not talking about the genius of Picasso, Mozart or Shakespeare - he is more interested in the general run-of-the-mill creativity that all humans have.

"We can doodle, tell stories, put together a poem. Can we also build systems that we can ask to paint us a picture?" he asks.

Single-minded

One of the biggest problems with such a goal is lack of data.

"The real world is the greatest dataset. Humans live in a rich, complicated world, and we come across lots of things. We see trees, landscapes, we talk, we communicate, we make jokes, but a computer doesn't know anything until we give it data."

And even machines that have been given the back catalogue of dead composers or thousands of pictures of famous paintings tend to have a narrow vision of their own creations.

"Human creators are capable of changing goals or values during the creative experience - they see the opportunity to do something differently but computers tend to be rather single-minded," he said.

Ultimately if you want a computer to be really creative, it will need a physical form, he thinks.

"If you did have embodiment, computers could start experiencing the world as we do, although it may experience the world differently and therefore will create differently."

- Published21 June 2015

- Published21 November 2014