How to turn your child into a video games designer

- Published

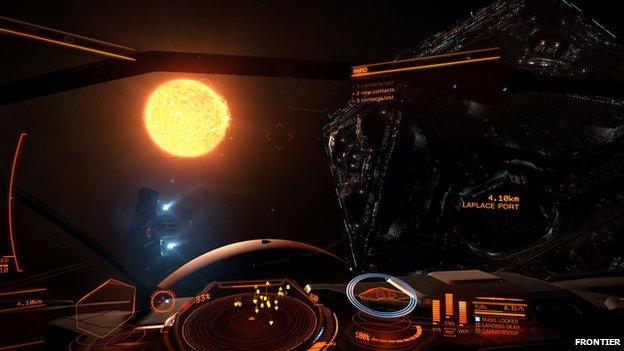

The next expansion for Elite Dangerous will involve landings on some planets

"I want to make games when I grow up."

It's an ambition voiced by many children. That is not surprising given that pretty much every one of them plays games on tablets, phones, consoles and PCs when they have a spare moment.

It is certainly my son's goal. And like any dutiful parent, I'm keen to help him realise his ambition - or at least help him find out early on if it's not for him.

I am also conscious that my lack of a formal technical background means that, at home, he'll struggle to get to grips with the core technical skill game making seems to demand - coding.

This is a problem. What I know about the history of video games suggests many of those that made it in the industry started young.

So, there was no better place to get answers about how to become a game maker than at Frontier Developments.

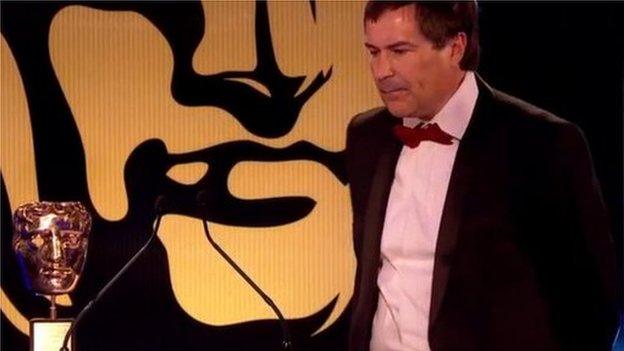

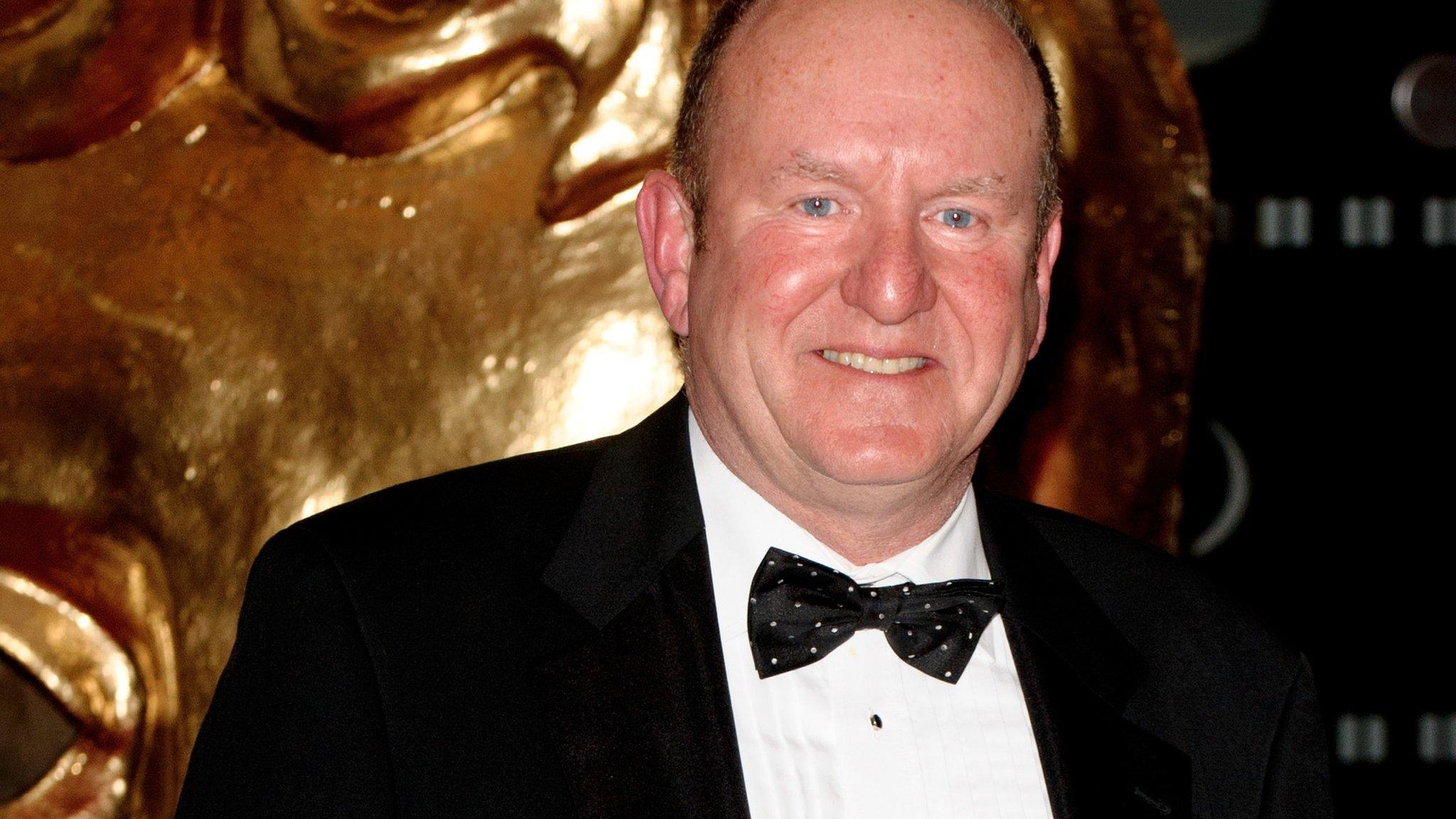

The firm was founded by David Braben - the archetypal child programmer who, while still a teenager, co-wrote the legendary game Elite.

David Braben was recently given a Bafta fellowship in recognition of his three decade-long career in games

Production values

The latest version of Elite was released late last year and Frontier is now almost fully occupied with maintaining and expanding the space trading and combat game.

Frontier employs a lot of programmers, says Adam Woods, a producer on Elite, and it has a well-established career path for them all the way from graduate-entry through to head of technology.

However, he says, there are plenty of other people at the firm that went via other routes. The studio's audio head, Jim Croft, started out as a musician and composer creating tunes for TV ads.

Making games is a great way into the game-making industry

Top tips for game makers by Shaun Spalding - Indie developer

Make Games.

The best thing you could possibly do is start making games today.

The reason I got my first job in the industry as a game designer was entirely down to the fact I was the only person who had his own finished video game to show off at interview.

Not only did this demonstrate my ability, knowledge and experience far better than anything else I could show or say, but it shows an ability to finish what I start, and that I have a natural drive to develop video games.

If you want to be a part of making games, make games today, and finish them. As many as you can. Show them to everyone you can and learn from everything you do wrong, which when you start off, will be almost everything.

Nothing else you do is more important than this when it comes to succeeding as a game developer.

Mr Woods knows his way around code but started out in QA - quality assurance - which involves playing Frontier games as they are being developed documenting bugs and crashes.

"Now, as a producer, I help define the road map for the game for a set period of time - it could be for the next year or the next couple of weeks," he says.

His job involves making sure the various teams at Frontier - coding, art, design, user interface, etc - are all on track to finish work on the next expansion or fix big bad bugs.

Creating a game like Elite Dangerous involves a wide range of skills beyond coding

"I break down the work that needs doing and get estimates about how long it is going to take," he says.

"Towards delivery date I will chase bugs and make sure it all comes together."

The producer role is just one of many that surrounds the programming heart of a game such as Elite Dangerous. Many of the people in those jobs are familiar with technology but coding is not essential to their day-to-day work.

Frontier has product managers that help co-ordinate the overall direction of the game, community managers who handle player feedback, and lots of graphic designers who work on creating and animating all the bits that make up a modern title.

Code course

That kind of diversity is to be expected in a sizeable studio such as Frontier, says Dr Jake Habgood, a former game-maker who now heads the software and games development degree course at Sheffield Hallam University.

"If you have more than 150 people in a team you get roles that are very specialised," he says.

For Dr Habgood, aspiring game makers would do well to grasp the difference between playing and creating.

"One of the common misconceptions that people who to this have is that making and playing games is synonymous," he says.

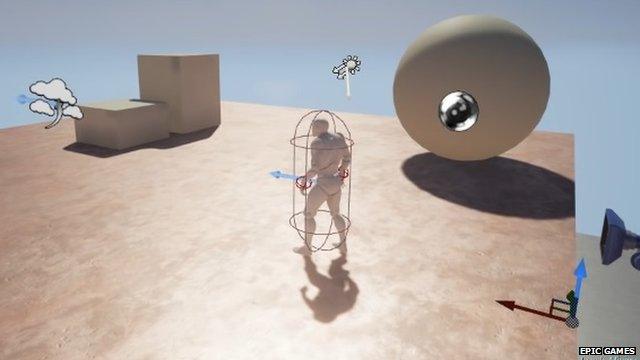

Tools like Unreal Engine 4 make it possible to create games by pointing and clicking

However, he adds, experts make what they do look easy while hiding what it took to master a skill. A game that is easy and fun to play would not necessarily have been as much fun, or as easy, to code and create.

For Dr Habgood, coding is the key skill to master for any aspiring game maker and the Sheffield course emphasises hands-on programming skills.

For youngsters, such as my 11-year-old, getting to grips with proper programming might be formidable but there were plenty of other ways to get a taste of game making without having to learn C++ or grapple with a command line.

Game designer shares his top tips

Tools including Scratch, external, Kodu from Microsoft, external, Game Maker by YoYo, external and even Unreal Engine 4, external make it more straight-forward to make games.

The most basic of these involves snapping virtual coding blocks together and even the more advanced ones, such as Unreal, conceal a lot of the in-depth coding.

That hands-on experience is key to understand the game-making process, says Dr Habgood, for no other reason than it will bestow an understanding of what is special about the craft.

"If you can find the creativity in programming and games you may see how compelling it can be," he explains.

Microsoft's visual programming language Kodu is entirely icon-based

Creative breakthroughs aside, seeing a game through to completion is quite an achievement for anyone at any age. It involves real work and exposes one other truth about the industry.

"It's very competitive and you have to be prepared to work hard and put a lot of hours in," he says. "If you don't, you won't make it."

"It's you that matters, not the degree," he adds.

"The degree will help but if you are not committed it will not help you get into the industry."

- Published21 August 2015

- Published20 August 2015

- Published20 August 2015

- Published9 October 2014

- Published6 August 2015