Horizon: How video games can change your brain

- Published

The creator of Neuroracer explains how it might benefit OAPs' brains

The video game industry is a global phenomenon. There are more than 1.2 billion gamers across the planet, with sales projected soon to pass $100bn (£65bn) per year.

The games frequently stand accused of causing violence and addiction. Yet three decades of research have failed to produce consensus among scientists.

In laboratory studies, some researchers have found an increase of about 4% in gamers' levels of aggression after playing violent games.

A growing body of evidence suggests video games can affect the brain's development

But other research groups have concluded factors such as family background, mental health or simply being male are more significant in determining levels of aggression.

What is certain is that science has failed to find a causal link between video games and real-world acts of violence.

But away from the controversy, a growing body of work is beginning to show these games in a different light.

Psychologists split over whether video games can make you violent

Motor skill

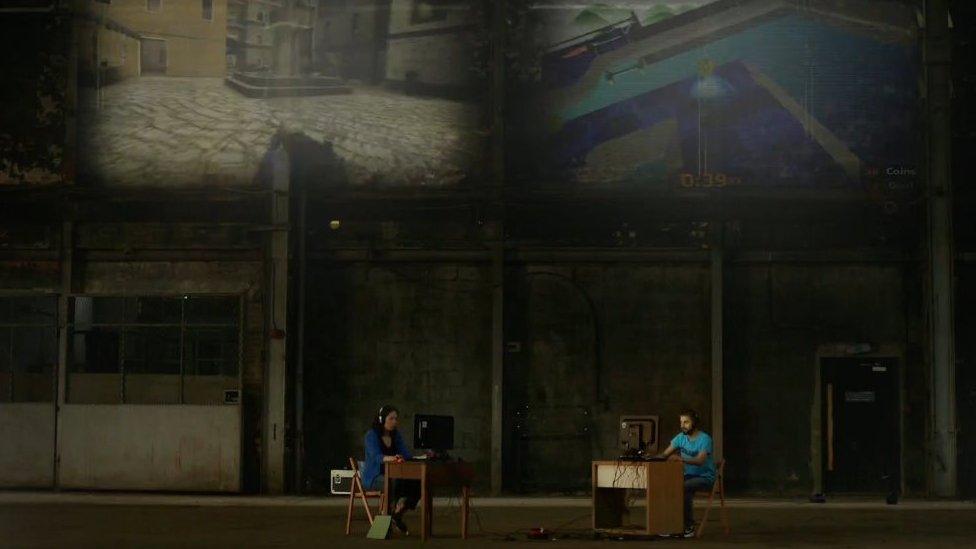

Dr Henk ten Cate Hoedemaker is the man behind Underground.

Underground's creator explains how it can help train keyhole surgeons

In the game, players must guide a child and her pet robot out of a mine.

But this is no ordinary game. Dr Hoedemaker is a keyhole surgeon, and Underground is designed to hone the skills of his profession.

Players use adapted controllers that mimic the tools used in surgery - and those who perform well in the game also do better in tests of their surgical skills.

Visual abilities

Around the world, other researchers are investigating the potential hidden benefits in video games.

At the University of Geneva, Prof Daphne Bavelier has compared the visual abilities of gamers and non-gamers.

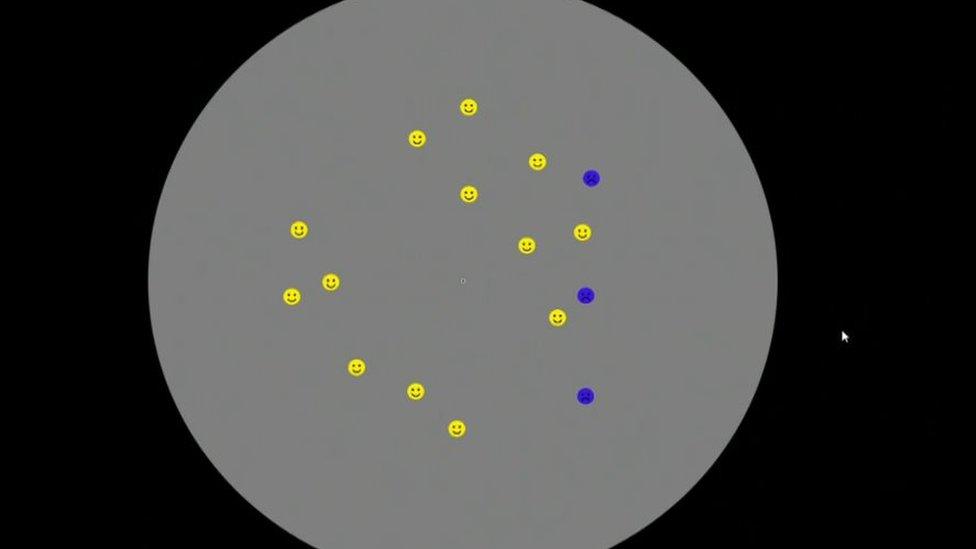

In one test, subjects must try to keep track of the position of multiple moving objects.

She has found that individuals who play action video games perform markedly better than those who do not.

Prof Bavelier's theory is that fast action games require the player constantly to switch their attention from one part of the screen to another while also staying vigilant for other events in the environment.

Prof Bavelier found action video gamers were better than other people at remembering which smiley faces in an experiment were blue

This challenges the brain, making it process incoming visual information more efficiently.

Brain growth

At the Max-Planck Institute of Human Development, in Berlin, Prof Simone Kuhn also researches the effects of the video games on the brain.

In one study, she used fMRI (functional MRI) technology to study the brains of subjects as they played Super Mario 64 DS, over a period of two months.

Remarkably, she found that three areas of the brain had grown - the prefrontal cortex, right hippocampus and cerebellum - all involved in navigation and fine motor control.

Volunteers had their brains scanned to study how they were affected by playing Super Mario

The visual layout of this game is distinctive: a 3D view on the top screen and a 2D map view on the bottom.

Prof Kuhn believes having to navigate simultaneously in different ways may be what stimulates brain growth.

Keeping sharp

Arguably the most exciting field of research is exploring the potential of video games to tackle mental decline in old age.

While electronic "brain training" games have long had enormous popular appeal, there is no hard evidence playing them has any effect beyond improving your score

But at the University of California, San Francisco, Prof Adam Gazzaley and a team of video game designers have created a game with a difference: Neuroracer.

Prof Gazzaley believes pensioners can improve their ability to multitask if they play the right kind of video games

Aimed at older players, it requires individuals to steer a car while at the same time performing other tasks.

After playing the game for 12 hours, Prof Gazzaley found pensioners had improved their performance so much they were beating 20-year-olds playing it for the first time.

He also measured improvements in their working memory and attention span.

Crucially, this showed that skills improved through playing the game were transferable into the real world.

Neuroracer players had to steer a vehicle and react to different signs at the same time

To test whether off-the-shelf games might bring similar benefits to elderly players, the BBC's Horizon programme recruited a small group of older volunteers from a sheltered housing complex in Glasgow.

They learned to play a popular karting game, clocking up about 15 hours each over five weeks. Their working memory and attention spans were tested before and after.

On average, both these scores increased by about 30%.

Although this was only a small test, larger scientific studies will continue to explore the effects of playing video games.

Horizon challenged some pensioners to play a Sonic the Hedgehog karting game

Prof Gazzaley believes we are only just beginning to tap their potential.

"I'm intrigued with the idea that in the future a psychiatrist or neurologist might pull out their pad and instead of writing down a drug, writes down a tablet game times two months, and uses that as a therapy, as a digital medicine," he says.

Horizon: Are Video games Really That Bad? will be shown at 16 September at 20:00 BST on BBC Two and will be on iPlayer afterwards.

- Published17 August 2015