The anatomy of a nation-state hack attack

- Published

A Chinese man faces years in jail after admitting helping hackers get at the computer systems of aviation firms such as Boeing

Cyber-security is not all about cyber-thieves. It is about cyber-spies too.

Mixed in among the spam, phishing messages and booby-trapped emails that land in your inbox might be the odd message crafted by hackers working for a government rather than a group of criminals.

Unfortunately, those messages are not odd in any other way. They look like every other net-borne threat. That is because the creators of these malicious programs usually exploit the same software vulnerabilities as mainstream malware, they can travel via the same hijacked PCs and they prey on the same human frailties that make the more typical stuff so successful.

PlugX has been attached to reports documenting human rights abuses in Tibet

Security companies have a hard time spotting them too, said Jordan Berry, a strategic intelligence analyst at security firm FireEye. Not least because the samples of malware cooked up by hackers backed by nation-states are small in number.

And, he said, the methods they use to infiltrate targets vary widely. Sometimes nations will dedicate a lot of time, talent and money to creating malware to work on their behalf.

That was the case with Stuxnet - a worm created to sabotage Iran's nuclear programme. Analysis of its electronic innards show it is a precision-guided weapon that probably took months to create. Stuxnet used four separate, previously unknown software vulnerabilities and only sprang into life when it found itself on a network with a very specific configuration.

Other similarly complex threats include Flame, Gauss, Regin and PlugX.

But, said Mr Berry, not every attack employs such finely crafted malware.

"Sometimes they may not need to use the big guns," he said. "so they use something just to get the job done."

The Stuxnet worm is widely thought to have been made by a nation-state to cripple Iran's nuclear programme

No matter which one hits a company or a government's network, exactly who was behind it becomes easier to understand once the malware gets to work.

"It's the context around it that's important," he said. "If its an attack on a Ministry of Foreign Affairs and there's not a lot of financial motivation behind it, then maybe it's a nation-state doing it."

Malware tour

In an attempt to get a better idea of just how sneaky nation-state malware can be, I asked Kevin O'Reilly from security firm Context IS to take me on a tour of the PlugX malware.

It was first discovered in mid-2012 and has been updated, altered and improved many times since then. It is believed to have been created by China and used in many campaigns against industrial targets in different nations as well as against dissident groups in Tibet and elsewhere, said Mr O'Reilly.

China seems to operate a franchise model when it comes to nation-state attacks, he said. As far as Context and others who watch Chinese malware can tell, the state creates the software and then hands it over to a lot of other groups who actually use it on its behalf.

However, said Mr O'Reilly, this was all conjecture as there was no direct evidence linking PlugX to China.

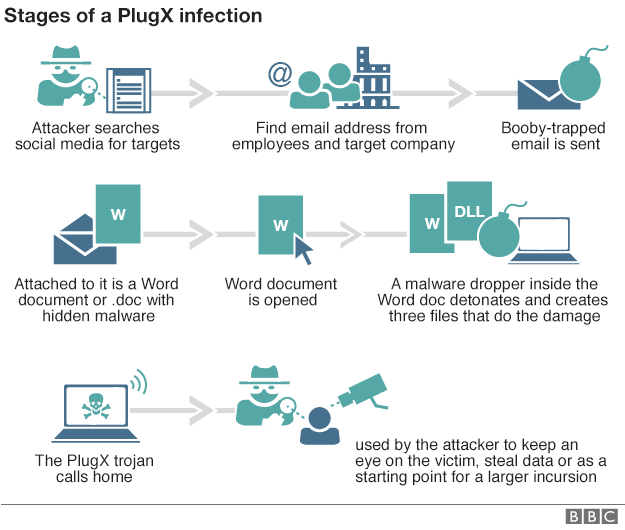

The modern version is pretty sneaky, he said, and uses several different techniques to infiltrate targets. The version I was shown around arrives as an attachment to an email.

The email is key to the attack, he said. The hacker groups that use PlugX typically do a lot of preparation before sending out booby-trapped email messages. They target a select group of people at one firm and craft the message to make it more appealing to them.

"Often," he added, "the documents are repurposed from legitimate sources, and 'weaponised' by embedding the exploit and malware dropper within them."

One of the documents that PlugX travels in was, ironically, a report about human rights abuses in Tibet.

Remote agent

Opening the document starts the process of infection. It gets in using an exploit or vulnerability in Windows that installs three files comprising the malware. The sneaky part is the way that two of these interact. One is a perfectly legitimate Windows file and as it runs it looks for a specific system file to get going.

Russia is also believed to be behind a lot of nation-state malware

PlugX includes the file it needs though this one is modified so it can install the actual malware. The way Windows works ensures it will use the one attached to the message rather than the safe one buried elsewhere on an infected computer.

"Once its got a foothold it makes sure it will run automatically with Windows and it will then phone home and be told to do whatever its controllers want it to do," said Mr O'Reilly. PlugX effectively gives attackers remote access to a computer on which it is installed.

"There's quite a lot of functionality built in," he said. "They might use the implant to get key logs or screen shots."

Its clear that it is doing different things to the run-of-the-mill malware that is looking to steal login credentials or credit card numbers.

"Ultimately," said Mr O'Reilly, "this is controlled by a person. It does not do much by itself."

Context is one of a few firms that have investigated breaches brought about with PlugX and it has used network forensics to replay where the attackers went and what they did.

"In one attack the intrusion was caught by the anti-virus and we were able to watch them go to the logs and try to clean them," he said. "They knew exactly where to go. That's the level of sophistication you are up against."

Robert Hanssen worked at the FBI for 27 years but is believed to have passed information to the Russians for 22 years

For veteran spy hunter Eric O'Neill, a former FBI agent who helped expose double agent Robert Hanssen, it should be no surprise that spies have gone digital.

"In the old days spies had to sneak into buildings to steal documents," he said. "Nowadays they don't. Espionage and spies have evolved."

A successful cyber campaign run by a nation-state could liberate far more information than any double agent could dream of securing, he said.

Attacks to steal data about people could well be carried out to give foreign powers a better idea of who was vulnerable and might be made to work for them.

"There are three main ways to recruit someone," he said. "Ideology, greed and blackmail."

Information in databases could give clues about medical conditions, debt or personal problems that might aid attempts to compromise an individual, he said.

"You have to know who you are attacking and whether they are more likely to swayed by ideology or greed or blackmail," he said.

"These types of attacks are not easy to do," said Mr O'Neill who now works for security firm Carbon Black. "But companies are foolish if they think that because it's hard they are not being targeted."

"These are spies, not hackers," he said. "You need to stop the spies, the people who are targeting other human beings. They are not just throwing stuff out hoping it hits."

- Published16 March 2016

- Published15 March 2016

- Published2 March 2016

- Published31 December 2015