Volunteers aid pioneering Edsac computer rebuild

- Published

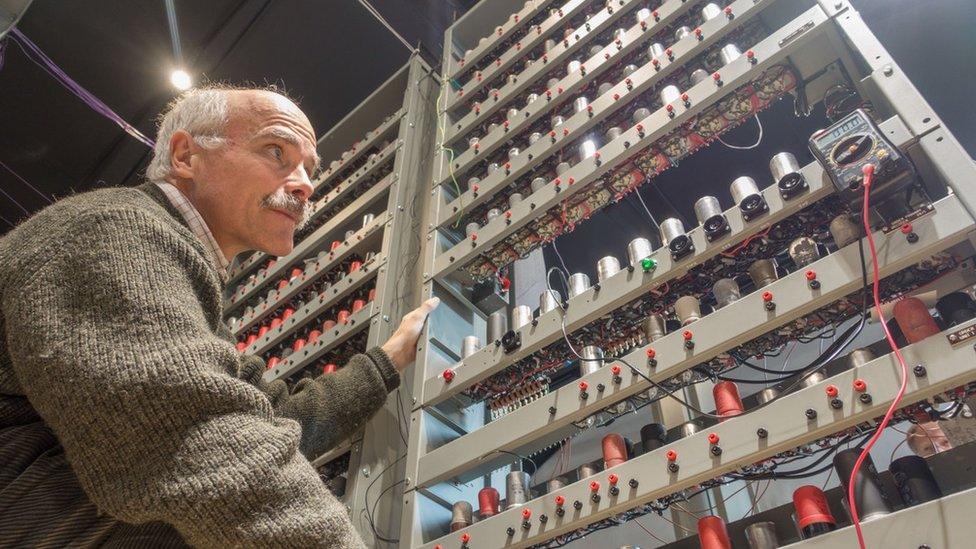

Each of the 140 chassis that form Edsac takes upwards of 20 hours to build and test

Think of a shed and objects like spades, forks and compost in a wooden hut at the end of the garden come to mind.

However, in the UK, some very old hardware is being brought back to life in some of those scruffy, but often well-organised, workspaces. In them, a group of veteran engineers is toiling to help recreate the pioneering Edsac computer.

Designed by Sir Maurice Wilkes, Edsac first ran in 1949 and was made to serve scientists at the University of Cambridge. It helped them push the boundaries of their disciplines by giving them a tool that could crunch numbers faster than they could ever manage.

"The problems they were tackling were not practical using hand-based calculation methods," said James Barr, one of the veterans reconstructing the Electronic Delay Storage Automatic Calculator.

Edsac quickly proved its usefulness and helped two Cambridge scientists win Nobel prizes.

Instruction set

But while the science was meticulously recorded, the building of Edsac was not.

"Wilkes was exposed to electronics and valves during his wartime work on radar and to the mercury delay lines it used for memory," said Mr Barr. "He had the technology in his head that he thought he could realise."

Wilkes' design for Edsac have been largely lost and, even if they could be found, that might not have helped because the machine changed as it was being built.

That, said Mr Barr, left the Edsac reconstruction project with a big problem. Namely, they did not have a clear idea of how the thing was wired up.

The project to recreate Edsac was undertaken to help fill gaps in knowledge about the way that this early British computer was built and worked. Once complete it will become a living exhibit at The National Museum of Computing where it will be used to help teach schoolchildren about programming.

The early months of the reconstruction scheme were taken up studying photographs of the finished computer to try to work out how its 3,000 valves were laid out and how they formed the logic that lent the machine its computational power.

Latterly, some plans for Edsac were discovered and have helped the builders confirm they were heading in the right direction. However, said Mr Barr, they turned up long after the heavy mental work had been done to understand the machine.

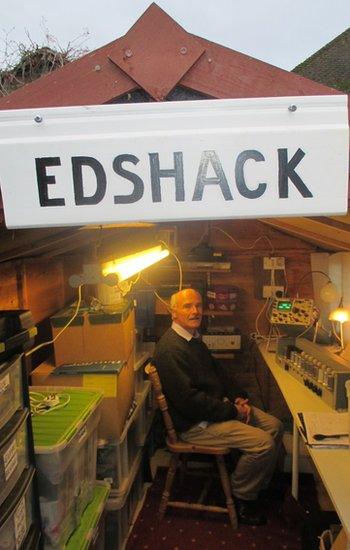

James Barr has toiled in his shed to get the Edsac chassis working

"It took me a year to understand its five-bit order code," said Mr Barr. But understand it he did and his insights, along with those from fellow engineers who have worked on other key parts of the machine, has helped the project recreate Edsac's innards.

Which is where the sheds come in.

Those logical parts are being turned into hardware, known as chassis, in sheds and attics up and down the country. This has involved huge amounts of work as Edsac is built of 140 chassis spread around a series of tall racks. Each one is about 80cm long by 60cm wide, studded with valve sockets and stands in front of a spider's dream of wiring.

"The practical reality is that the construction effort is quite significantly painstaking and it takes 20 to 40 man hours per chassis," he said.

This wiring work is so mentally draining that Mr Barr and his fellow volunteers can only work on a chassis for a couple of hours at a time.

"I didn't know what I was getting into when I volunteered but I've loved it," said Mr Barr, who got involved after seeing a poster about the Edsac reconstruction when visiting The National Museum of Computing at Bletchley Park.

Coming together

Mr Barr studied at Cambridge during the 1970s and was lectured by many of the men who built Edsac, including Wilkes. He has dubbed his back garden work space the "Edshack" to honour this connection.

"I thought I had to get involved as much as a homage to Maurice Wilkes and to give something back because they have given so much to me, really," he said. "They set me up for a lifetime career of well-paid work and I was very grateful to them."

About 60% of the chassis have now been finished, said Mr Barr, and that means the project can move on to its next phase - getting all those separate parts to work together. "It's not easy," he said.

In some respects, the modern-day team is facing the same problems that the pioneers back in the 1940s faced. They knew it should and would work, it was just a case of making it happen.

The integration stage is being aided using tools unavailable to Wilkes and his peers, said Dr Andrew Herbert, overall project manager for the Edsac reconstruction.

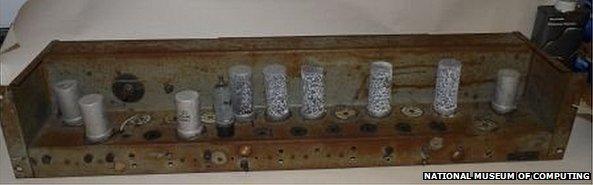

Some parts of the original Edsac are still in existence

"What is working in our favour is that we use modern computing to test 1940s electronics," he said. "It's giving us a real advantage that we can use to run the chassis through different conditions."

Despite the help from these tools, getting all the parts to click is tricky.

"We are finding all the classic integration problems," he said. "Different parts of the machine are expecting things at different voltages and times."

Progress is slow but there is no doubt that the machine is now coming together.

"By early spring we will able to demonstrate fetching a number out of the store, giving it to the accumulator, adding one to it and then sending it back," said Dr Herbert.

That might sound trivial but it is the basis of all machine-based computation. Getting that working will be a strong signal that the whole project is on the right track and that the machine will be recreated successfully.

"We hope we will have a working machine by the summer next year," said Dr Herbert. "We are not counting our chickens yet but they are at least heading towards the hen house."

- Published29 June 2015

- Published3 February 2015

- Published26 November 2014

- Published25 June 2014