AirBnB racism claim: African-Americans 'less likely to get rooms'

- Published

- comments

AirBnB is an online service which allows people to rent out rooms in their homes, or even entire properties

People with names that suggest they are black are being discriminated against on room sharing site AirBnB, a Harvard study suggests.

A survey of more than 6,000 hosts, external in five US cities concluded that names that sounded African-American were about 16% less likely to get a positive response to a request for a room when compared against white-sounding names like Brad or Kristen.

In a statement, AirBnB admitted it faced "significant challenges" over the issue.

It invited collaboration with "anyone that can help us reduce potential discrimination in the Airbnb community".

It added: "We are in touch with the authors of this study and we look forward to a continuing dialogue with them."

AirBnB is an online service which allows people to rent out rooms in their homes, or even entire properties. The site has has more than two million listings in more than 190 countries.

Identical requests

The study was carried out by a trio of Harvard Business School researchers. They noted that AirBnB's model of presenting lots of detail about both hosts and guests paved the way for discrimination.

The five cities studied were Baltimore, Dallas, Los Angeles, St Louis, and Washington DC.

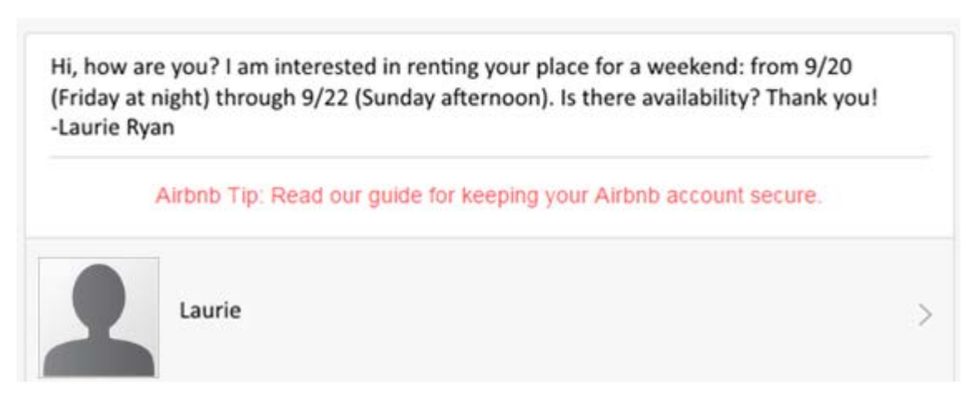

This is a sample message sent to an AirBnB host

Researchers made profiles that were identical other than the names used. Hosts were approached with requests to stay at the advertised properties.

When profiles had white-sounding names like Todd and Allison, there was a 50% success rate for a positive response - ie they were offered the room.

But with the black-sounding names - such as Darnell and Tamika - that figure dropped to 42%. The authors noted that the variation was consistent with "contexts ranging from labour markets to online lending to classified ads to taxicabs".

The study suggested that black hosts were just as likely to discriminate against black people as white hosts were.

There was no significant difference between the activity of male or female hosts.

Researchers said the racial discrepancy did not exist in the hotel industry, as often bookings are made automatically and without the host seeing a guest's name beforehand - which is the proposed solution the authors suggest to AirBnB.

"[AirBnB] could conceal guest names, just as it already prevents transmission of email addresses and phone numbers so that guests and hosts cannot circumvent AirBnB's platform and its fees," the authors say.

"Communications on eBay's platform have long used pseudonyms and automatic salutations, so AirBnB could easily implement that approach."

They also suggested AirBnB encouraged more users to use its "instant book" option which allows guests to book rooms without the need for prior approval from the host.

Subconscious

AirBnB said instant booking was becoming increasingly popular, with one in five hosts using the feature - up from one in 12 in 2014.

However the site said it was not planning to stop making users use real names to book rooms as they felt it was an important part of maintaining trust and confidence between hosts and guests.

However Prof Ben Edelman, one of the study's authors, told the BBC he felt the real-name policy was excessive.

"They require you to reveal your name, but to what end? What good does that do? AirBnB says it increases accountability - but how does it?

"It's important that AirBnB know the person's name, but we don't think the prospective host needs to know the prospective guest's name."

The study authors conclude that while the internet can be a great leveller when it comes to race and social class, the same discriminations in the real world still exist, even if just subconsciously.

The paper cites other studies showing subtle differences where race is a factor. In one study of sales on free listing site Craigslist, researchers found that buyers were less likely to respond to an advert selling an iPod if the accompanying picture showed the device being held by a black hand rather than white.

Furthermore, a separate study by dating site OkCupid in 2014, external revealed that even if users answered yes to questions asking if they were open to dating people of a different race, their actions in contacting matches and replying to approaches regularly contradicted that assertion.

The explosion of social media was reversing early positives the web offered when it came to limiting discrimination, Prof Edelman said.

"If you buy something on Amazon, you're not going to get any racial discrimination, whereas you may have done in a physical store," he said.

"But the recent changes on the internet, having more pictures, more social connections, we've been making it worse."