Ray Tomlinson's email is flawed, but never bettered

- Published

- comments

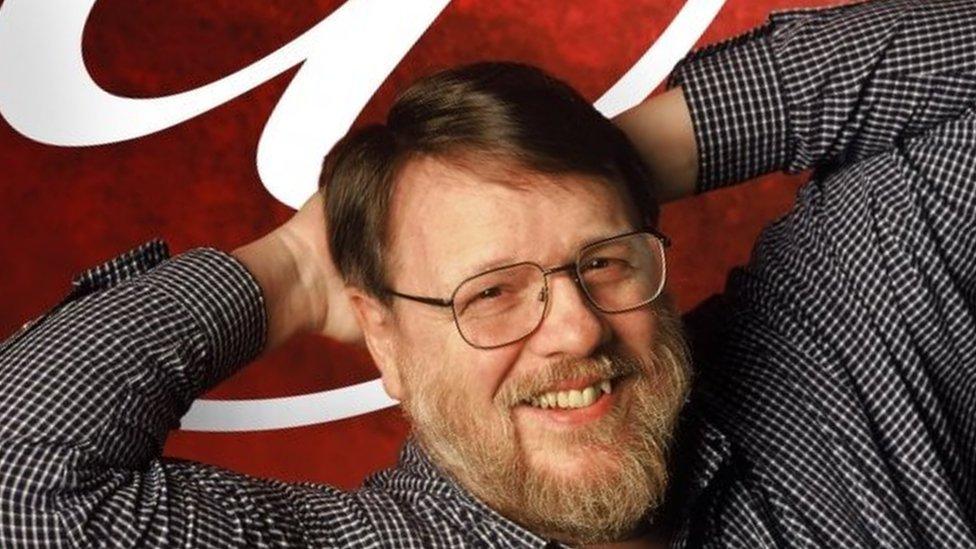

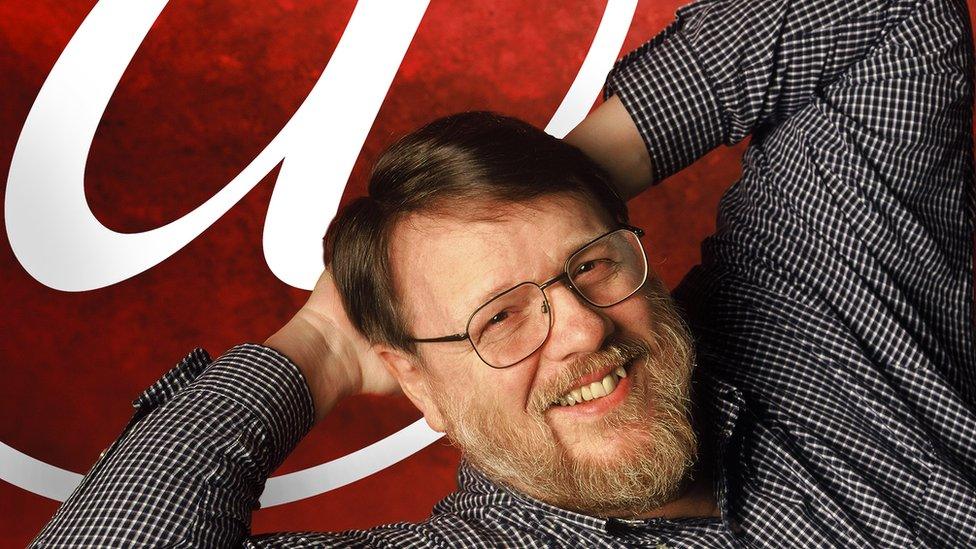

Ray Tomlinson is credited with inventing emails in 1971

The internet pioneer Ray Tomlinson has died, aged 74.

He is widely regarded as the inventor of email, and is credited with putting the now iconic "@" sign in the addresses of the revolutionary system.

He could never have imagined the multitude of ways email would come to be used, abused and confused.

Just think - right now, someone, somewhere is writing an email she should probably reconsider. Count to 10, my friend. Sleep on it.

Another is sending an email containing brutal, heartbreaking words that, really, should be said in person… if only he had the nerve.

And of course, a Nigerian prince is considering how best to ask for my help in spending his fortune.

Email does curious things to us. We worry about getting emails, we worry about not getting emails.

Before joining the BBC, I'd live by the popular freelancer's mantra that a watched inbox never fills, so I'd go for a walk in the hope of returning to offers of work.

Now I'm desperate for "inbox zero".

Email became part of everyday life so quickly we didn't have enough time to learn how to properly use it - until there was no turning back, and bad habits were set in stone.

To make things worse, the Blackberry brought email away from our computers and into our palms - and therefore our bedrooms, our commutes and our toilet breaks.

In doing so, we willingly let email seep into our lives, instigating an anxiety we'd not yet encountered. One study in 2014 took email away from 13 US government workers. The result? Their average heart-rates decreased.

And that's because for anyone with any kind of office job, the temptation - or perhaps pressure - to be on top of your emails can be overwhelming.

In France, there have even been calls to enforce some kind of "digital work hour" restriction, because checking your email after work is, after all, free labour.

The first email

Below is an extract from Ray Tomlinson's account, external of how he created email:

I am frequently asked why I chose the at sign, but the at sign just makes sense.

The purpose of the at sign (in English) was to indicate a unit price (for example, 10 items @ $1.95). I used the at sign to indicate that the user was "at" some other host rather than being local.

The first message was sent between two machines that were literally side by side. The only physical connection they had (aside from the floor they sat on) was through the Arpanet.

I sent a number of test messages to myself from one machine to the other. The test messages were entirely forgettable and I have, therefore, forgotten them.

Most likely the first message was QWERTYUIOP or something similar. When I was satisfied that the program seemed to work, I sent a message to the rest of my group explaining how to send messages over the network.

The first use of network email announced its own existence.

'Completely forgettable'

Yet, for all its faults, we've still not found anything better.

Which is why, as the technology world mourns the loss of Ray Tomlinson, it's only right to spend a moment to appreciate what a remarkable contribution he made to the business of communication.

He's credited as sending the first email as we know it today - and commandeering the @ symbol as a way to simplify how it works.

The first messages were sent between computers that were a mere 10 feet apart, but the feat was enormous.

For something so groundbreaking, it was adorably anti-climactic. Just read how he described it during an interview in 2009.

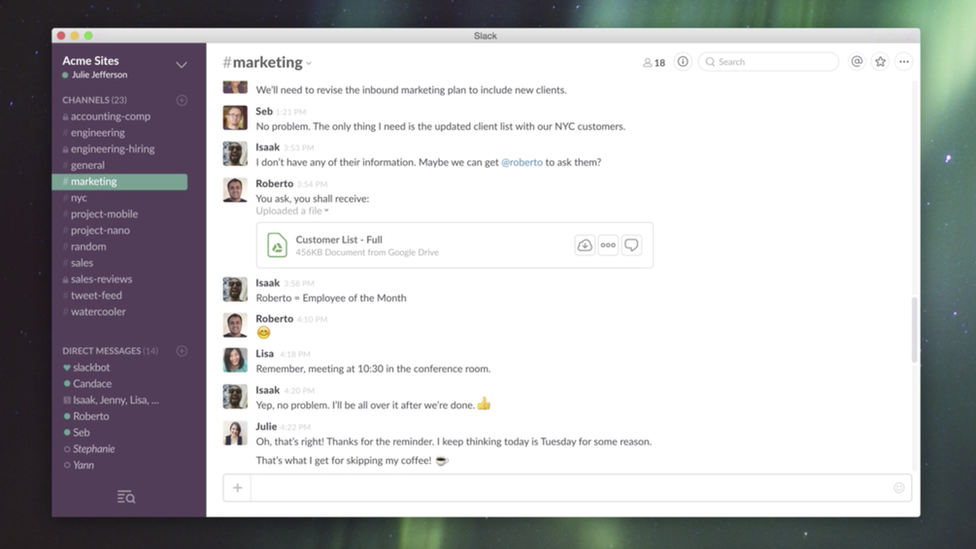

Sites like Slack want to replace emails - even if just internally

"Every time you test you have to generate some sort of message.

"You might drag your fingers across the keyboard or just type the opening phrase from Lincoln's Gettysburg address or something else - so technically the first email is completely forgettable and therefore forgotten."

In the following decades, the @ sign has gone from being a barely-used character to one we use multiple times a day. As NPR put it, external, Mr Tomlinson changed @ from a symbol into an icon.

Yes there's spam. Yes there's phishing attacks. Yes there's work mailing lists that ding constantly, or "reply all" fiascos.

But email itself has never been the problem, just the people that use it.

Post-email

That said, one hopes email is replaced one day. It's widely accepted that it's not an efficient communication method, and disrupts the focus of anyone trying to get things done.

But what could possibly come next?

Facebook At Work is being trialled by several companies - but could be broadened out soon

In the past year we've seen companies like Slack try and reinvent workplace communication, but while such tools are great for chatting internally, it does little to improve talking to those who work outside of your company.

In its quest for world domination, Facebook has long wanted us to ditch using email and instead shift over to using the Facebook inbox.

But I don't know about you, my Facebook inbox is one of the few safe spaces I have on the internet: an area where work does not overflow into my personal life. I'd like to keep it that way.

Soon, we're expecting Facebook will expand its Facebook At Work service, offering it to all businesses around the world. It's being trialled by a selection of firms, including the likes of RBS and Heineken. The idea is that communication tools we're all familiar with when talking to our friends can surely help us chat at work. Minus the cat videos.

If Facebook provides a way to separate work life from personal life, then great. Like Slack, it seems to work best when talking to people you already work with. If the rest of it just becomes a place to send and receive messages in chronological order... that's just an email inbox in disguise.

And we're back to where Ray Tomlinson started in 1971. 1971! This is an industry that moves quicker than any other, where start-ups come and go in a matter of weeks.

And yet Mr Tomlinson's innovation has endured for 45 years - and shows no sign of going anywhere yet.

Follow Dave Lee on Twitter @DaveLeeBBC, external and on Facebook, external

- Published6 March 2016

- Published10 April 2014