Can Micro Bit replicate BBC Micro success?

- Published

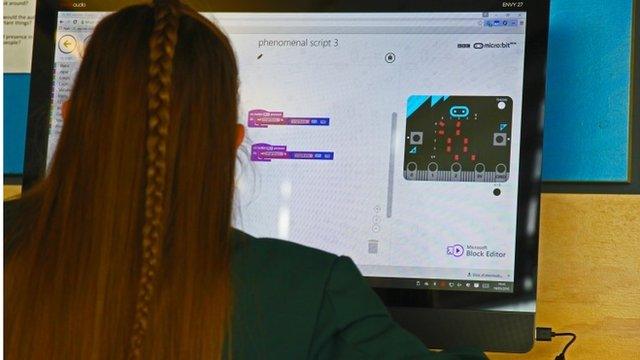

The Micro Bit comes with a wealth of material to help children

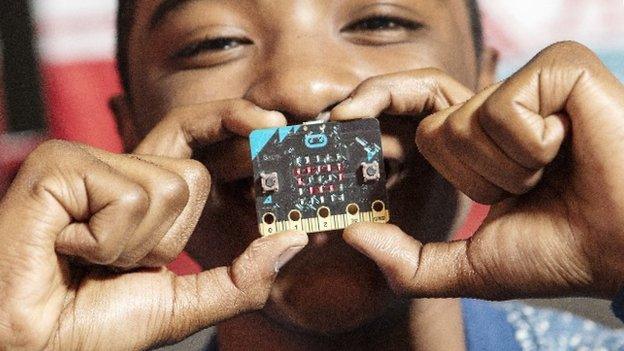

The BBC's Micro Bit finally launched last week just as the children headed off for the Easter holidays.

Many won't get their hands on the tiny computers until they return from their spring break in mid-April, although the hope is that some will play with their new devices at home over the vacation.

The BBC has bigger ambitions for the little machine, hoping that it will help kickstart a revolution in coding in the same way as its big brother the BBC Micro did in the 1980s.

But how will the Micro Bit - which currently is only on offer to 11 and 12-year-olds around the UK - inspire a generation and what exactly will it inspire them to do?

Computer history

The project is late - and there was clearly a rush to get it into the hands of children before most schools broke up for Easter.

This delay is perhaps unsurprising - it is a complex task launching new hardware especially with the huge range of partners that the BBC is working with - but it has frustrated teachers who are hastily rewriting lesson plans, initially slated for the beginning of the academic year.

It mean that schools now only have one term to start using the device in classrooms and, perhaps more worryingly, when this year group of students leave the classroom at the end of the summer term they will take the Micro Bits with them, thanks to a decision to give the devices to individuals rather than to schools.

"It is vital that there is a fresh supply of Micro Bits each year for it to have a long-term, sustainable future," said Bill Mitchell, director of education at the British Computing Society (BCS).

The BBC has said that the devices will be made commercially available from next year although there is little detail about how this will work or how much they will cost.

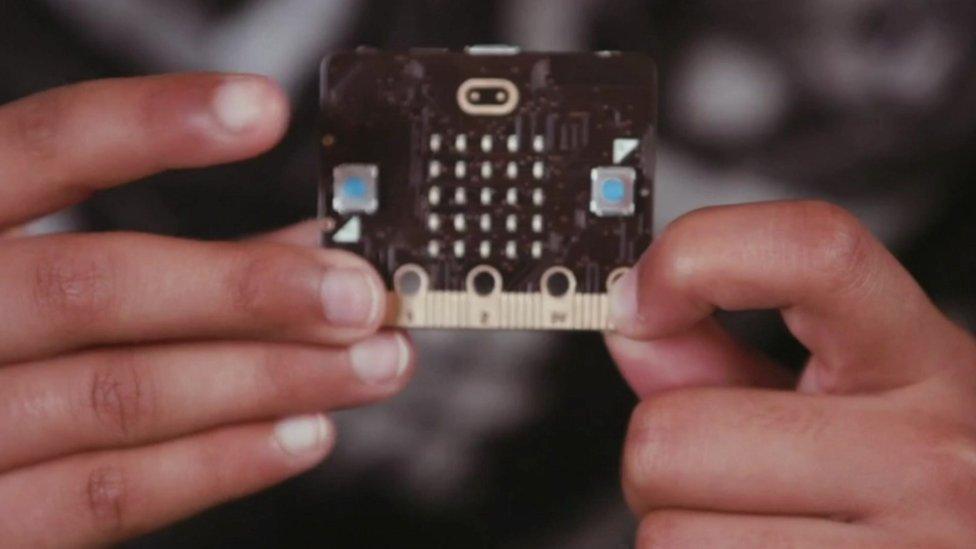

The BBC Micro has a place in the UK's computing history

The BBC Micro became the centrepiece of the BBC's first computer literacy push in the 1980s and a hugely influential piece of kit.

When it hit the market, an estimated 60% of primary schools and 85% of secondary schools adopted it and many of the influential leaders in the technology industry now cite it as having been crucial to their computing careers.

Now those willing the Micro Bit to succeed hope for similar.

"Many of our volunteers and staff say that they learnt to code using a BBC Micro and we want to replicate that with the Micro Bit," said Code Club director Clare Sutcliffe.

Separate to the roll-out of the device to a million schoolchildren, the BBC is also making extra ones available to after-school clubs such as Code Club.

"We will be getting 20,000 Micro Bits in a few weeks time and we plan to give them to the venues so that they can be used over and over again," said Ms Sutcliffe.

Computational thinking

There is no doubting the fun that children can have with the Micro Bit and it has already inspired a bunch of interesting projects but what is the longer-term goal of the technology?

Those who argue in favour of the hands-on approach to computer science say that, just as children learning about Shakespeare need to see the Bard's plays performed to truly understand the work, so those learning about computing need to get under the bonnet.

Those involved in the Micro Bit launch want it to inspire a new generation

"The Micro Bit is a device that interacts with the physical world and children can see that the device can have a physical effect, which helps them understand how computation can solve problems in the real world. That is hugely important," said Mr Mitchell.

He hopes it will create a new generation of school leavers who can "analyse real-world problems and find an algorithm to solve them", which he said will not only put the UK leaps and bounds ahead of other countries but will also help those children as they enter adult life - whatever profession that they choose to pursue.

"There is a misapprehension that the new curriculum is about churning out a generation of computer programmers but that is not the case," said Mr Mitchell.

"It is about creating a generation of children who can think computationally."

Hardcore programming

That is something governments around the world are recognising and back in 2014 the UK overhauled the ICT curriculum, which had drifted from teaching hardcore programming in the 1980s to classes about how to use Word and create a spreadsheet from the 1990s onwards.

And in the US, President Barack Obama pledged to provide $4 billion in funding for computer science education in US schools.

The UK's national curriculum now acknowledges that "high quality computing education equips pupils to use computational thinking and creativity to understand and change the world".

The shift in thinking harks back to the era of the BBC Micro although this time around, Mr Mitchell hopes to inspire more than just the computer geeks.

"In truth the BBC Micro only reached around 10% of children - those who were interested in hardcore programming. For the rest, it was just far too challenging to get to grips with," he said.

The onslaught of new, user-friendly programming languages coupled with gadgets such as the Micro Bit offers a whole new world of opportunity, he thinks.

The BCS estimates that a quarter of UK schools are doing "an excellent job" in implementing the new computer science curriculum.

The challenge now, said Mr Mitchell, is to convince head teachers in the other three-quarters to put computer science on a par with subjects such as maths and English.

CODING REVOLUTION

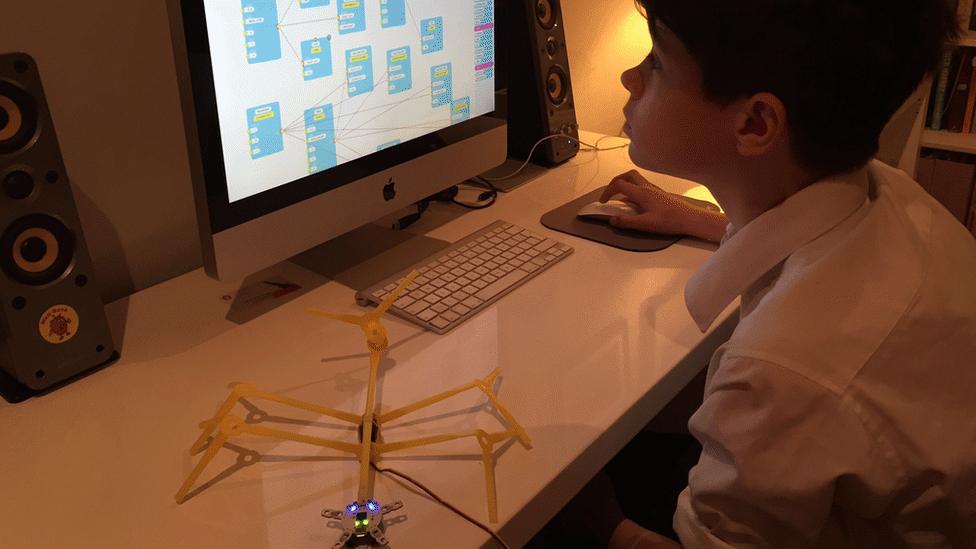

The quirkbot is a codeable creature made of motors, lights and drinking straws

Micro Bit is not the only tiny computer on the market - CodeBug is another similar device designed to introduce kids to programming.

And Swedish start-up Quirkbot is shipping a little device that allows children to programme and construct a creature out of LED's, motors and drinking straws.

It is working with five Swedish schools and a dozen others around the world to create classroom content for its device.

My son is a year too old to get his hands on the first generation of Micro Bit, but he had a go at programming a Quirkbot for a recent STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths) project at his school.

Archie turns his hand to programming a little straw creature for a school project

As a parent what I noticed was the pride he took when the programming worked.

He agreed that it was worth the effort.

"I found it hard to begin with but I got to grips with it using trial and error. I felt a sense of achievement when I made it move and light up. I think it is a useful tool, but personally I find it challenging."

- Published22 March 2016

- Published22 March 2016

- Published21 March 2016

- Published10 March 2016