Back to the Satoshi Nakamoto Bitcoin affair

- Published

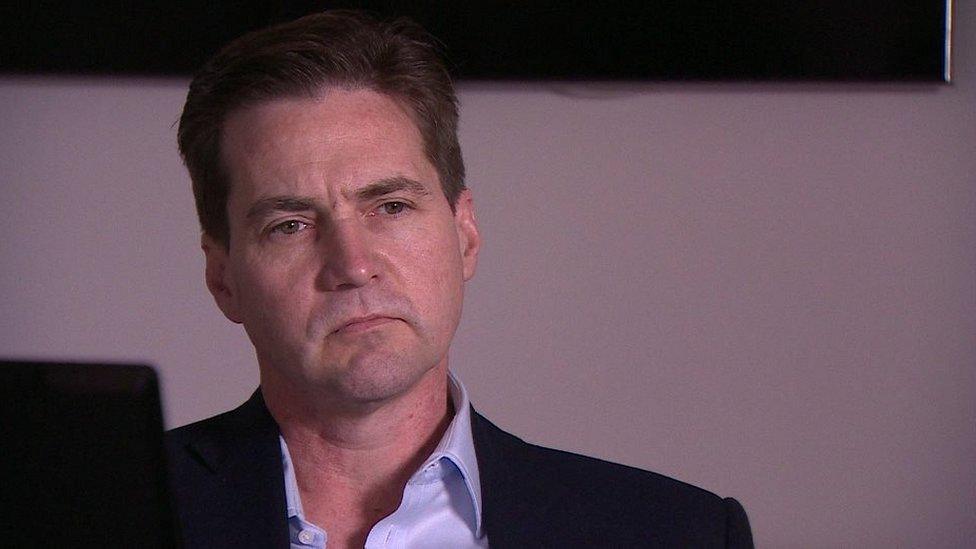

Craig Wright failed to deliver on his promise of "extraordinary proof" that we was Bitcoin's inventor

At the beginning of May, it seemed that a great mystery had been solved.

An Australian academic and entrepreneur, Craig Wright, identified himself as Satoshi Nakamoto, the creator of the crypto-currency Bitcoin.

But, over the following days, the proof he offered was torn apart, not just by angry people on the Bitcoin forums but by a number of authorities on cryptography.

After first promising more evidence, Dr Wright then wrote a blog saying he did not have the strength to continue and retired from public view.

Nakamoto's true identity appeared as opaque as ever - the Australian had not proved his case, but nor had it been disproved.

Now, though, we have a whole new collection of evidence, in the form of a 35,000-word article about the Nakamoto affair in the London Review of Books, external.

The author is the journalist and novelist Andrew O'Hagan, whose work includes a fascinating and hilarious account, external of his time trying to be the ghost writer of Julian Assange's autobiography.

It seems Mr O'Hagan has an appetite for driven and difficult high-performing geeky types, because he spent six months with Craig Wright.

The value of Bitcoin has strengthened against "real" currencies since Dr Wright disappeared from view

That meant he was there right through the period when Dr Wright was first outed as a potential Nakamoto last December, then dismissed as a fraud, and later through his own "self-outing" and the aftermath.

It is a gripping and beautifully written tale, more a short novel than a magazine article.

We learn all sorts of new details about Dr Wright's career, his claims about his involvement in the creation of Bitcoin, and his reasons for choosing to identify himself as Nakamoto seven years after the currency was created.

To me, the key revelation is about this motivation.

He had told the BBC that he had not wanted to come out into the spotlight but needed to dispel damaging rumours affecting his family, friends and colleagues.

But O'Hagan shows us something rather different - a man under intense pressure from business associates who stood to profit from him if he could be shown to be Nakamoto.

These people had signed a deal with Dr Wright in June last year, which saw them pay off his debts, including legal fees incurred in a battle with the Australian tax authorities.

Then, they had a plan for him.

"They would bring Wright to London and set up a research and development centre for him, with around 30 staff working under him," O'Hagan writes.

"They would complete the work on his inventions and patent applications - he appeared to have hundreds of them - and the whole lot would be sold as the work of Satoshi Nakamoto, who would be unmasked as part of the project."

The intellectual property, which he had already created and would now augment, would be worth as much as $1bn (£700m) with the Nakamoto name attached, so they would all end up very rich indeed.

That may sound fanciful, but Dr Wright's research was into the block chain, the technology underlying Bitcoin, and the world's big banks are rushing to invest in exploring its potential.

Now, they may have had dollar signs in their eyes, but Dr Wright's backers certainly seemed to believe he was Nakamoto, and O'Hagan outlines some new evidence that supports that view.

He spends days talking to Dr Wright about his relationship with Dave Kleiman, an American who died in 2013 and is thought by many to have played a big part in the creation of Bitcoin.

With some reluctance, Dr Wright eventually supplies some emails that seem to suggest the two worked together on the 2008 Nakamoto white paper explaining the idea of the "peer-to-peer electronic cash system".

Dr Wright gave interviews to only the BBC, the Economist and GQ magazine, in addition to speaking to Mr O'Hagan

O'Hagan goes to meet Dr Wright's ex-wife, who stands up a story about the two men meeting at a conference in Orlando in 2009 - because she came along too.

She gives a detailed account of their meeting and the way Dr Wright hero-worshipped Mr Kleiman, which rings true coming from someone who has no reason to lie.

There is a document about a trust fund set up by Dr Wright to hold some bitcoins for Mr Kleiman, along with a promise not to reveal the identity behind Nakamoto's email address.

And there are minutes of a meeting between the Australian tax authorities and Dr Wright's business, where his advisor appears to suggest that he possessed 1.1m bitcoins - worth nearly £600m at the current exchange rate.

There is also an intriguing tale about a meeting between Dr Wright and Ross Ulbricht, the man now serving a life sentence in the United States for setting up the Silk Road, the bitcoin-fuelled drug and gun trading site.

And, then, we get a behind-the-scenes account of what happened when this brilliant, difficult, angry man - described by one colleague as "like Steve Jobs but only worse" - went public, in separate meetings with the BBC, the Economist and GQ, and the days afterwards, when everything fell apart.

As someone who played a part in that saga - and still asks himself whether he should have asked better questions of Dr Wright - I was just a little disappointed with this climax to the story.

The author seems more removed from the action at this point than in the months before the denouement.

Here is an example: on the Wednesday after the big reveal on Monday 2 May, Dr Wright agreed to undertake a much simpler proof of his identity than he had offered before.

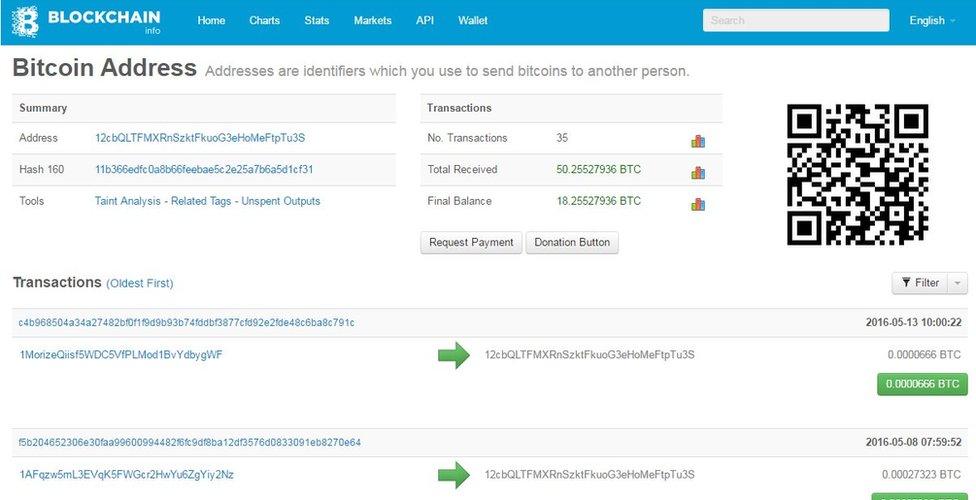

He asked me, and the two Bitcoin experts who had verified his story - Jon Matonis and Gavin Andresen - to send a small amount of bitcoins to an address known to be linked to Nakamoto.

He would then send it back, proving his claims to the identity.

Others have also transferred small amounts of bitcoins to Nakamoto's address without them being returned

The money was sent but never returned.

What was going on in the hours between us being invited to take part in this proof and the moment when we were told it was "on hold"?

The only reason we get for Dr Wright's bizarre behaviour, which sabotaged everything he had worked for, comes in the form of an email to O'Hagan.

He sends the writer a news story that suggests the father of Bitcoin might be arrested for helping to facilitate terrorism by allowing people to buy weapons anonymously.

Dr Wright, it seems, decided he would prefer to be called a fraud than risk spending years in jail.

This seems unconvincing.

After all, he had been planning to out himself for months - albeit under pressure from his backers - so why this sudden fear of the consequences now?

The other question left hanging is why the backers who had invested so much in their Nakamoto had not demanded more proof from him at an earlier stage.

In the end, we are left uncertain about Dr Wright's true role in the creation of Bitcoin.

It seems very likely he was involved, perhaps as part of a team that included Dave Kleiman and Hal Finney, the recipient of the first transaction with the currency.

He may have exaggerated his contribution, he may have constructed a very elaborate fantasy - or this fragile personality may have lost his nerve as he realised that his life would never be the same again once he was Craig "Nakamoto" Wright.

If you are expecting O'Hagan to reveal the truth behind Bitcoin's creation myth, you will be left disappointed.

But if you enjoy a ripping yarn - with some piercing insights into geek culture - then you will find the Satoshi Affair an engrossing way to spend a couple of hours.