Moorfields, Google - and a problem with sharing

- Published

It is a fascinating experiment that brings together Google's artificial intelligence division and one of the world's leading centres for the treatment of eye conditions.

But the research project that has seen Moorfields Hospital hand over retinal scans to DeepMind has already proved controversial - and, for me, it all feels rather close to home.

For the past 10 years, I have been a regular visitor to Moorfields, where I receive excellent treatment for a longstanding condition.

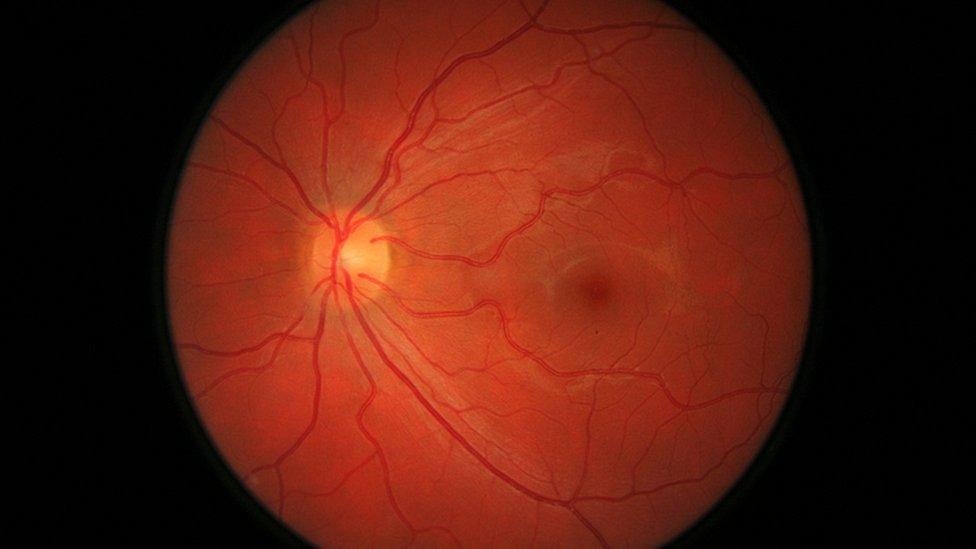

This includes having pictures taken of the back of my eye, and it seems likely that these photos may be among those handed to DeepMind, external.

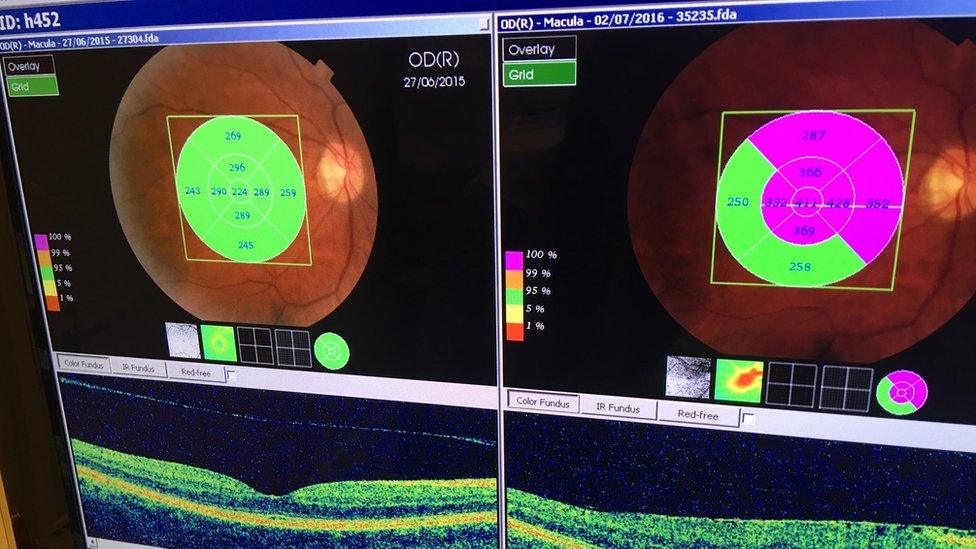

This is for a project that aims to work out whether machine-learning technology can give doctors a better understanding of eye disease.

On hearing of this project, some privacy campaigners cried foul on the grounds that patients were not being asked if they wanted their data to be handed over.

But Google and Moorfields say that since the data was anonymised, they were not obliged by the information commissioner's rules to seek permission from patients.

Moorfields Hospital told me that any data collected from patients is assumed to be available to research projects undertaken by the hospital or its partners.

Patients can opt out - but that would mean withholding data from all projects, rather than just this one.

Now, I can imagine that some people who would be generally happy to see their data used in research will still be uneasy about it going to Google, whatever the guarantees of anonymity.

Retinal photographs are used to monitor eye health

That does not apply to me. I have heard so much about the potential of big data to improve healthcare - and so little evidence that it is happening - that any privacy concerns are, for me, outweighed by impatience for progress.

But here is the irony. Moorfields may be good at sharing our data with Google - but sharing my data with the hospital or more widely across the health service is much harder.

At the weekend, I went for an eye test with the excellent optician who first spotted my condition and referred me to Moorfields.

The practice is fitted out with advanced equipment almost as good as that at the hospital, and my eyes were examined and photographed in all sorts of clever ways

There was a minor issue that the optician spotted and wanted a consultant to see at some stage.

But she then revealed that she was unable to simply email the photos to Moorfields, because the hospital's systems did not allow that.

She recommended that I take a picture of the scans on my phone and then show them to the consultant on my next visit.

This seemed bizarre to me, but I have since spoken to another optician who confirmed that this was the case across the NHS.

"If we are referring a patient we have to print out the scan and put in the post - or if it's urgent we fax it across," he told me.

"Of course, a fax is black and white, so not much use."

The problem, it seems, is inadequate and incompatible IT systems, coupled with an NHS still not really comfortable with email as a means of communication.

Concerns about privacy and security of email may also be an issue.

My problem with my eye scans may seem like an isolated incident, but many who work in the NHS agree that it is symptomatic of a wider cultural problem.

The collaboration between Moorfields Hospital and Google is just the kind of project that excites those who dream of an artificial intelligence revolution transforming healthcare.

But the more prosaic business of dragging health service IT into the 21st Century may be more important to patients in the short term.

- Published5 May 2016

- Published5 July 2016