Black Hat: Chip and pin hack spits out cash

- Published

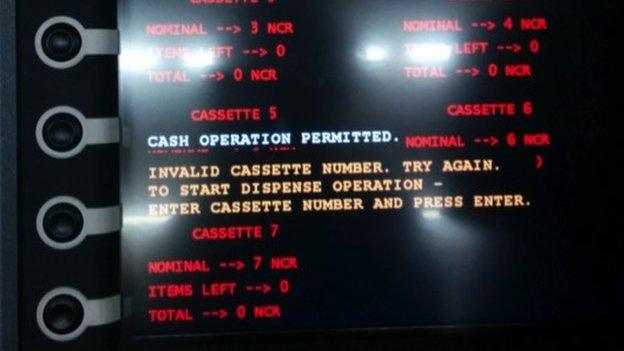

Dollar bills were dispensed from an ATM using the hack

A vulnerability in the widely-used “chip and pin” system has been exploited to make a cash machine spit out money.

Researchers speaking at the Black Hat conference in Las Vegas demonstrated how small modifications to equipment would allow attackers to intercept the systems used to authorise payments.

The team was able to make a mostly unmodified ATM dispense hundreds of dollars in cash.

While chip and pin is widely used across Europe, the US is only now beginning to use the technology - making it a renewed target for hackers, the researchers said.

“In the US we are finally catching up to the rest of the world and using chip and pin,” said Tod Beardsley, security research manager for Rapid7 who oversaw the hack.

"The state of chip and pin security is that it’s a little oversold."

Attackers could use a 'out of order' sign to cover up what was being done to the ATM, researchers said

The security and specifications of chip and pin are looked after by EMVCo, a consortium of six major payment providers - American Express, Discover, JCB, MasterCard, UnionPay, and Visa.

EMVCo could not be reached for comment on Wednesday.

Money man

While Rapid7 went into some detail about the hack, specifics were not shared to prevent the technique being copied.

Rapid7 has disclosed the vulnerability to major ATM makers and banks, though it would not specify which. The team said it had not seen any effort to rectify the problem, but that it hoped the firms were looking into the vulnerability.

The hack is essentially performed in two halves. Unlike the older magnetic stripe system, in which criminals can skim the card info and use it at will until the card is cancelled, chip and pin provides only a limited window for transactions to take place - adding, in theory, a far better layer of security.

Criminals begin by modifying a point-of-sale (POS) machine, adding a small device known as a shimmer which sits between the victim’s chip and the receptor in the machine into which the card is inserted.

The shimmer reads the data on the chip, including the pin being entered, and transmits that to the criminals. In the second half of the hack, criminals use an internet-connected smartphone to download the data from the stolen card, and then essentially recreate that same card in any ATM.

“The modifications on the ATM are on the outside,” Mr Beardsley explained to the BBC.

"I don’t have to open it up. It’s really just a card that is capable of impersonating a chip. It’s not cloning."

The ATM can then be instructed to constantly draw out cash.

While each card could only be spoofed for a limited amount of time - a few minutes, perhaps - Mr Beardsley suggested criminals could have a vast network of modified POS points with a steady rate of unsuspecting victims providing constantly “active” cards.

“You could shim 20 or 30 POS systems and have a constant stream. You’ll have plenty of time to spit money out of ATMs."

Follow Dave Lee on Twitter @DaveLeeBBC, external and on Facebook, external

- Published3 December 2015

- Published8 October 2014

- Published18 July 2016

- Published30 December 2013