Micro Bit mini-computer heads overseas

- Published

The Micro Bit was given to schoolchildren across the UK in March

The Micro Bit mini-computer is to be sold across the world and enthusiasts are to be offered blueprints showing how to build their own versions.

The announcements were made by a new non-profit foundation that is taking over the educational project, formerly led by the BBC.

About one million of the devices were given away free to UK-based schoolchildren earlier this year.

The BBC says they encourage children, especially girls, to code

However, the delayed rollout of the machines to last year's Year 7s (11-to-12-year-olds) caused problems for teachers who had less time than expected to prepare related classes.

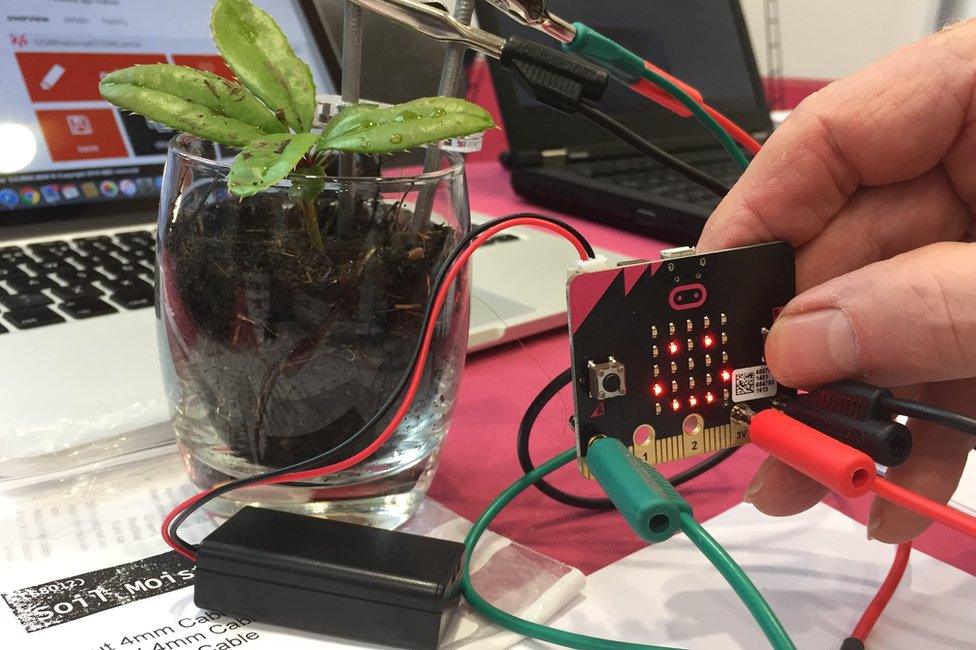

One Micro Bit project involves using the device to check that plant soil is damp enough

Global ambition

Beyond the UK, Micro Bits are also in use in schools across the Netherlands and Iceland. But the foundation now intends to co-ordinate a wider rollout.

"Our goal is to go out and reach 100 million people with Micro Bit, and by reach I mean affect their lives with the technology," said the foundation's new chief executive Zach Shelby.

The Micro Bit Educational Foundation is being led by Zach Shelby, who previously worked at the chip-designer ARM

"That means [selling] tens of millions of devices... over the next five to 10 years."

His organisation plans to ensure Micro Bits can be bought across Europe before the end of the year and is developing Norwegian and Dutch-language versions of its coding web tools to boost demand.

Next, in 2017, the foundation plans to target North America and China, which will coincide with an upgrade to the hardware.

"We will be putting more computing power in," Mr Shelby said.

"We will be looking at new types of sensors.

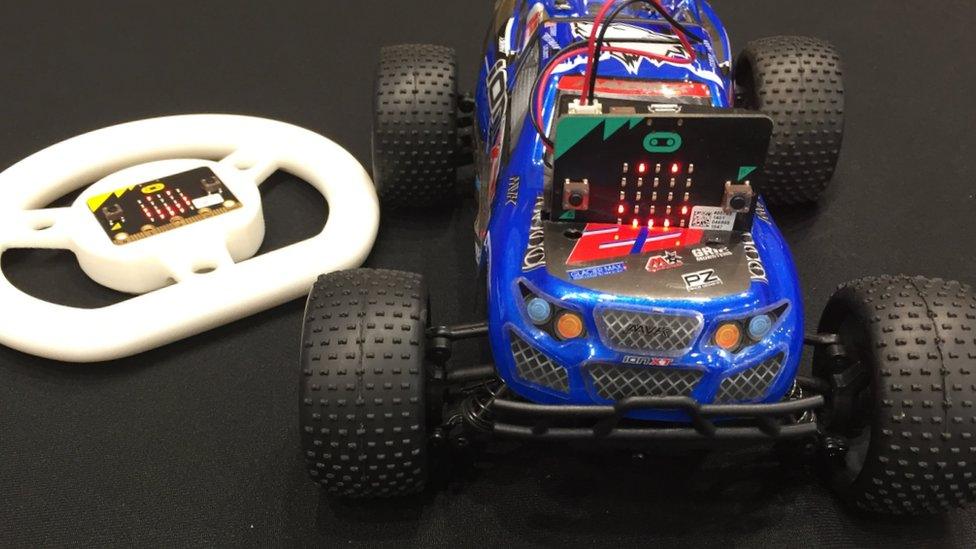

Micro Bits have been used to create a remote control car and its motion-tracking steering wheel controller

"And also how to display Chinese and Japanese characters - it turns out you need a lot more LEDs than we have today.

"We also have work to do to reduce the price for developing countries, that's something we're very aware of."

Micro Bits currently sell for about £13, excluding the batteries needed to power them.

That makes them several times more expensive than another barebones computer - the Raspberry Pi Zero.

But the foundation says they serve different audiences since the Micro Bit is designed for users with little or no coding knowledge when they begin.

What is a Micro Bit?

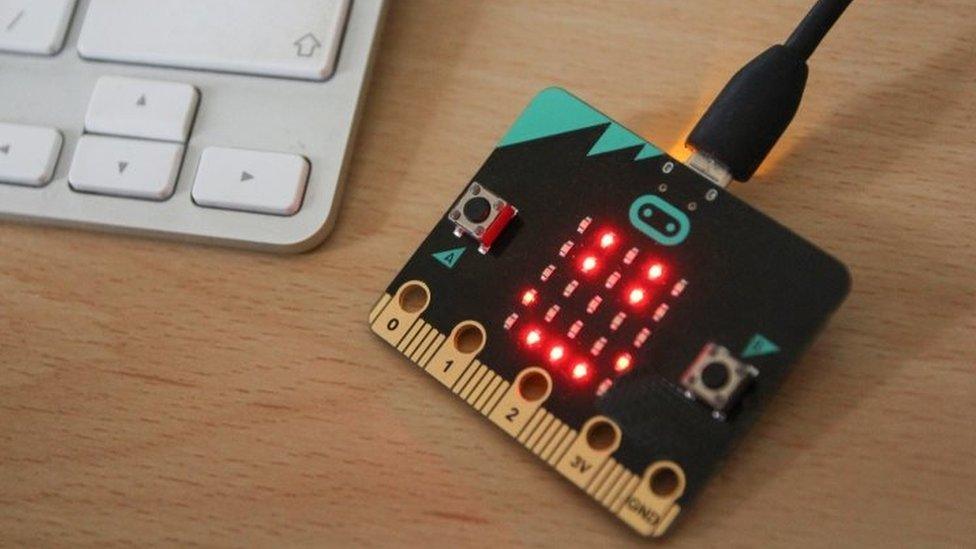

The Micro Bit is a palm-sized circuit board with an array of 25 LED lights - that can be programmed to show letters, numbers and other shapes - and a Bluetooth chip for wireless connectivity.

It also includes two built-in buttons, an accelerometer and compass, and rings to which further sensors can be attached.

Rather than enter code directly into the computer, owners instead write their scripts in a choice of four programming languages via web-based tools on a PC, or via an app on a tablet or smartphone.

Once written, the compiled scripts must be transferred to the Micro Bit, which then functions as a standalone device that can be used to flash messages and record movements among other tasks.

It can also be attached to other electronics to form the "brain" of a robot, a musical instrument or other kit.

In addition, a new feature makes peer-to-peer communications possible, meaning one Micro Bit can now transmit data to another, opening up further possibilities.

UK expansion

Rishworth School sent a Micro Bit into the stratosphere

The foundation has also pledged to use some of its funds to sponsor Micro Bits for UK classrooms, so that more children get the chance to use them.

However, for the most part, schools wanting to use them will need to pay for the units themselves.

That is likely to require two or more pupils having to share a device in class rather than being given one of their own to take home, as had been the case.

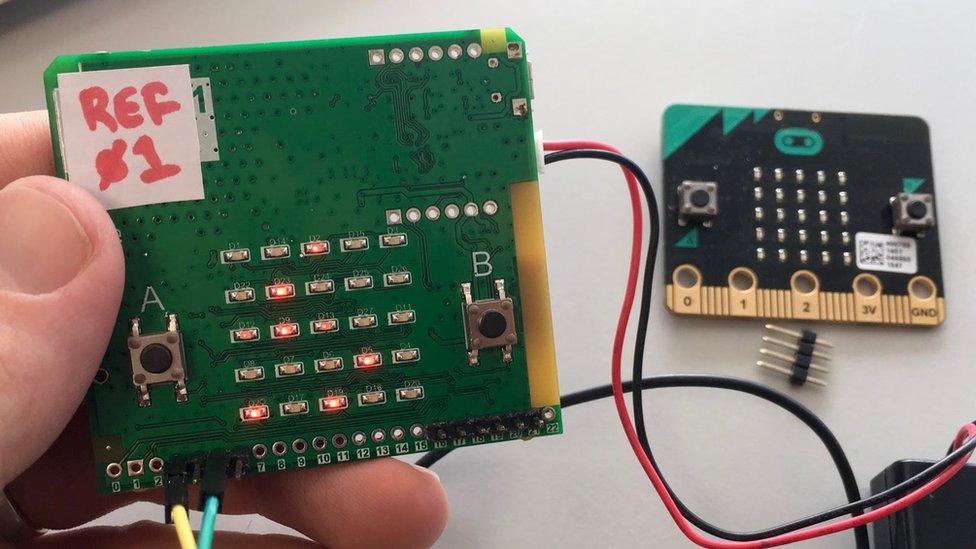

Older children are also being courted with the release of the Micro Bit's hardware design, so that they can build DIY models.

Enthusiasts will be able to build their own Micro Bits

"It will look different because building it yourself is not easy," said Mr Shelby.

"We think that will get older kids and young adults interested in experimenting with electronics.

"They can not just make a Micro Bit but modify one and make their own sensors."

Female appeal

Although the BBC is relinquishing control of the project, it will retain a seat on the foundation's board and the hardware will still be branded with its name.

To mark the handover, the broadcaster released details of a survey that questioned 147 girls before they received a Micro Bit, and then a different group of 208 girls afterwards.

Users code the Micro Bit using a different computer before transferring their programs

It recorded that 23% of those without experience said they would "definitely" study computing in the future, but the figure grew to 39% for those who used a Micro Bit.

"A lot of projects in Stem [science, technology, engineering and mathematics] are oftentimes aimed at boys - rocket cars for example," commented Mr Shelby.

"With Micro Bits there have been lots of projects that are really interesting to girls - they love music-based projects and making their own drawing games with it, for example - so it seems non-intimidating."

Early days

The Micro Bit's original release was delayed from October 2015 to March 2016, meaning teachers got them late in the school year.

Some of those involved in the project believe it is too early to judge their impact fully as some recipients have only just started using them.

"If we could have allowed the teachers to have them a couple of weeks before the students, that would have had a bigger impact," acknowledged Richard Needham, a consultant at Stem Learning - a firm that develops teaching resources.

"Some schools found it quite difficult to manage because they were asked to distribute these but it wasn't clear who had ownership of them.

"The BBC said they belonged to children and not teachers, but I do know in some schools the teachers hung on to them for a little bit longer to decide how they were going to distribute them.

"I've heard of some rare examples where teachers only gave them out at the start of this school year, which was a disappointment, but understandable."

- Published19 October 2016

- Published31 May 2016

- Published29 March 2016

- Published22 March 2016