Facing the robotic revolution

- Published

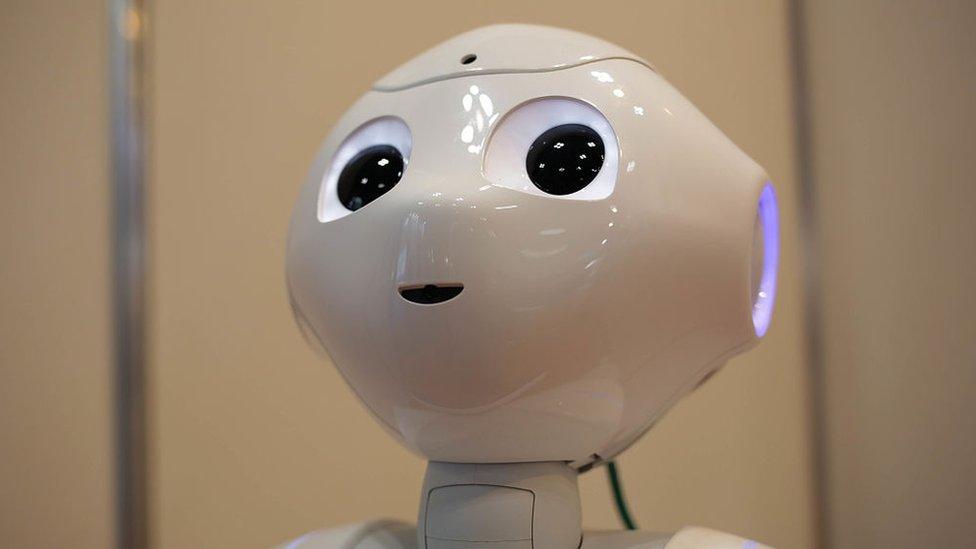

Pepper awakes. "Hi, I am a humanoid robot, and I am 1.2m [4ft] tall. I was born at Aldebaran, external in Paris. You can keep on asking me questions if you want."

Michael Szollosy, who looks at the social impact and cultural influence of robots, has just switched on the new arrival at the Sheffield Robotics, external centre, at the University of Sheffield.

He asks: "What do you do, Pepper, external?"

"Human."

"You do human?" I interject.

"Of course not," says Pepper, "but that shouldn't keep us from chatting."

I say indeed not, and ask what he thought of Paris.

"You can caress my head or hands for example," is the reply. "Very Parisian," I observe, stroking the sensors atop of Pepper.

"I like it when you touch my head. Ah, miaow."

"You're a scream, Pepper."

Mark Mardell meets Milo

"Miaow ! I feel like a cat!"

Pepper is slim white robot, with skeletal hands, a plastic body and big black eyes.

Mr Szollosy says: "Human beings don't need very much to identify something as alive.

"So a couple of black dots and a line underneath and we see a face every time.

"People say, 'Oh he's smiling at me,' - his mouth doesn't move. But that's what humans bring to the equation.

"We invent these things. I say robots were invented in the imagination long before they were built in labs."

This project is less about developing the technology and more about examining the way we relate to it - most people working in this field are convinced Pepper and and his kind will have huge implications for all of us, changing the way we work, the way we live, even the way we relate to each other.

"I think it is going to be increasingly the case that robots do more and more of the jobs that people used to do," says the centre's director, Prof Tony Prescott.

"We have lots of Eastern Europeans weeding fields because nobody in the UK wants to do that. It could be automated. It's a perfect job for a robot to do."

We are now at a tipping point.

The advances in AI (artificial intelligence) mean robots can now do much more.

But it hasn't developed in the way people might have expected 50 years ago.

A computer can do really clever stuff - beating a chess grandmaster, external with ease, and now winning at Go.

But a robot butler, which could make you a cup of coffee and run your bath, remains out of reach.

Taking jobs, not terminating humans, may be the biggest threat posed by robots

The very idea of robots excites and scares. It is part of the reason behind this centre.

After the development of genetically modified (GM) food, also known in the tabloids as "Frankenstein food", and the backlash against it, they decided some education was called for.

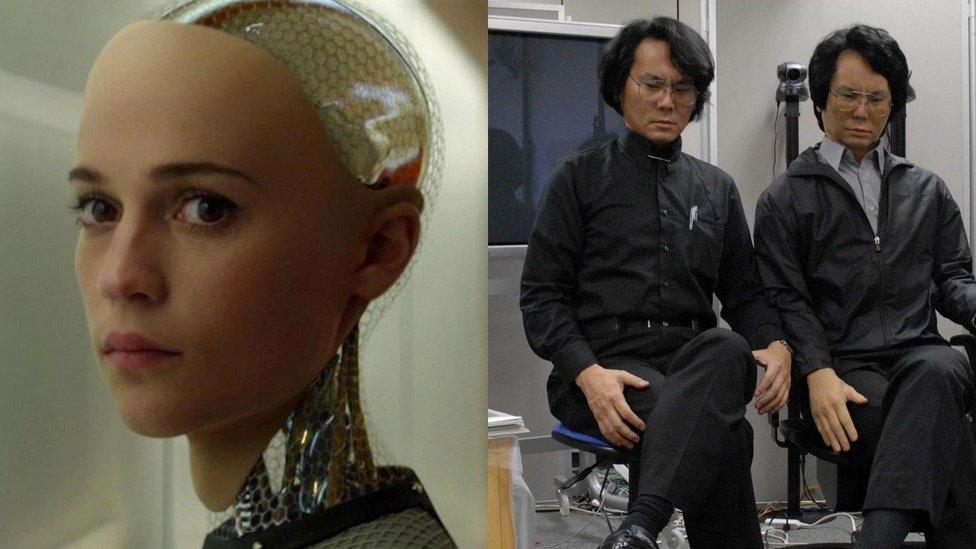

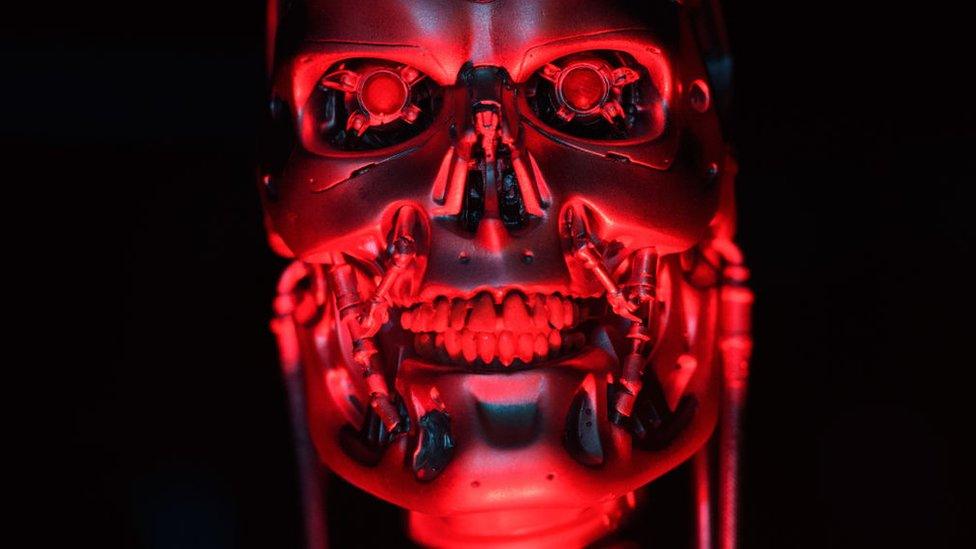

Mr Szollosy says people are frightened by the wrong things. He bemoans the fact that any story about robotics is accompanied by a picture of the Terminator.

"If artificial intelligence does want to take over the world, eradicate the human race, there are much more efficient ways of doing it," he says.

"Gun-wielding bipedal robots - we could beat them no problem. Daleks can't go upstairs.

"My job is to make people understand what not to fear but also explain that robots may well take 60% of the jobs in 20 years' time and that is of deep concern, if we don't restructure society to go along with that."

Prof Prescott hopes robots are part of the solution to a problem that haunts politicians.

"We have a shortage of trained carers, and it is often migrant labour," he says.

"Those jobs are very poorly paid.

"The quality of life for people in care is low, the quality of life for the carers is also low.

"I would like to protect the right to human contact in law, but people with dementia may need a lot of physical help and a lot of that can be provided by robots."

Paro is a furry communications robot

Milo, with a chunky body and a mobile face under anime-style hair, is designed to mimic human expressions to help autistic children, external.

But some of those he manages I've never seen on a real person.

MiRo, external is much cuter, looking somewhat like a dog, a donkey or a rabbit.

"It's designed to mimic the behaviour of animals," says Sheffield Robotics' senior experimental officer Dr James Law.

"For patients, particularly the elderly, particularly with Alzheimer's and dementia it is akin to pet therapy, which can have a lot of value for people who need more social interaction in their lives."

Still MiRo is not very cuddly. Unlike Paro, external.

I would say he's a very sophisticated furry toy seal, squeaking as you stroke his sensors, flashing big black eyes as you caress him.

Dr Emily Collins is interested in using such robots in children's wards, where real animals and even fur is a danger.

"I'm very interested in what mechanism is going on between a human and an animal which results in increased neuropeptide release, so they need less pain medication," she says.

"Being able to replicate that in paediatric wards, where you cannot have animals, would be fantastic.

"I don't see the point in a humanoid robot, apart from the fact people like the form and the shape.

"As soon as you make a robot look like a human analogue, people have expectations that the robot is going to do the same as a person, and we can't replicate that."

Many car production lines have been automated, but what next?

It is a really interesting debate, and one that maybe one day we'll have to face. But there are far more pressing problem.

If Mr Szollosy is right and robots take 60% of the jobs by 2037, what does he think will happen?

"The jobs are going to go," he says.

"There is going to be greater unemployment. Maybe we need to recast our society so that becomes a good thing, not a bad thing."

Prof Prescott says: "If people aren't able to sell their labour, then the whole market struggles because the people producing still need people to buy.

"So maybe we need to pay people to consume, maybe through some basic income, external.

"I think it is inevitable that we go in that direction. It's good news.

"The possibility now exists we can put over a lot of the work we don't like to robots and AIs."

The idea of "the basic, external" would face huge political opposition.

But it's worth noting that many who work in the field think there are few alternatives, even if there has to be an economic crisis before it's taken seriously.

This is not the same as interesting questions for the future about robot rights or consciousness - these problems are coming toward us with, well, the speed and ferocity of the Terminator.

Mainstream politicians are only just beginning to take notice.

You can hear Mark Mardell's report for The World This Weekend, plus a debate about what the future holds for robots and jobs, via BBC iPlayer.

- Published11 September 2015