Intelligent Machines: Do we really need to fear AI?

- Published

It may be a long way off but if we do reach a point where machines are truly intelligent, what rights should they have?

Picture the scenario - a sentient machine is "living" in the US in the year 2050 and starts browsing through the US constitution.

Having read it, it decides that it wants the opportunity to vote.

Oh, and it also wants the right to procreate. Pretty basic human rights that it feels it should have now it has human-level intelligence.

"Do you give it the right to vote or the right to procreate because you can't do both?" asks Ryan Calo, a law professor at the University of Washington.

"It would be able to procreate instantly and infinitely so if it and its offspring could vote, it would break the democratic system."

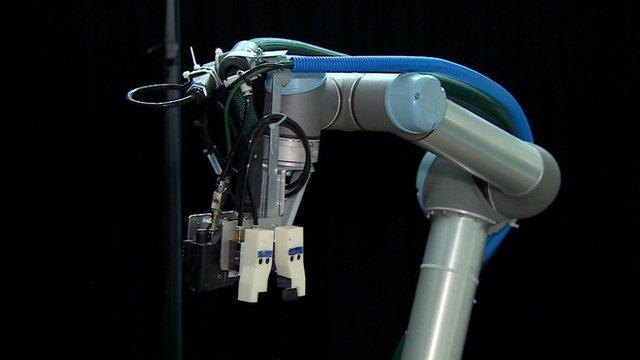

If an industrial robot goes rogue, who is to blame?

This is just one of the questions Prof Calo is contemplating as he considers how the law has to change to accommodate our ever-growing band of robot and AI companions.

He does not think that human-level intelligence is coming to machines any time soon but already our relationship with them is raising some interesting questions.

Recently there was a tragic accident at a VW factory in Germany, when a robotic arm, that moved car parts into place, crushed a young man who was also working there.

Exact details of the case are not yet released but it is believed human error was to blame.

Volkswagen has not commented on the incident.

While industrial accidents do happen, the law gets a little fuzzy when it involves a robot. It would be unlikely that a human could sue a robot for damage, for example.

"Criminal law requires intent and these systems don't do things wrong on purpose," said Prof Calo.

How the world deals with the rise of artificial intelligence is something that is preoccupying leading scientists and technologists, some of who worry that it represents a huge threat to humanity.

Will the AIs of the future keep humans in a zoo for their own amusement

Elon Musk, chief executive of Tesla motors and aerospace manufacturer Space X, has become the figurehead of the movement, with Stephen Hawking and Steve Wozniak as honorary members.

Mr Musk who has recently offered £10m to projects designed to control AI, has likened the technology to "summoning the demon" and claimed that humans would become nothing more than pets for the super-intelligent computers that we helped create.

The pet analogy is one shared by Jerry Kaplan, author of the book, Humans Need Not Apply. In it, he paints a nightmarish scenario of a human zoo run by "synthetic intelligences".

"Will they enslave us? Not really - more like farm us or keep us on a reserve, making life there so pleasant and convenient that there's little motivation to venture beyond its boundaries," he writes.

Human intelligence will become a curiosity to our AI overlords, he claims, and they "may want to maintain a reservoir of these precious capabilities, just as we want to preserve chimps, whales and other endangered creatures".

AI experts aren't worried about robots chasing us down the street despite popular images of evil machines intent on our destruction

Philosopher Nick Bostrom thinks we need to make sure that any future super-intelligent AI systems are "fundamentally on our side" and that such systems learn "what we value" before it gets out of hand - King Midas-style.

Setting the controls for AI should come before we crack the initial challenge of creating it, he said in a recent talk.

Without clearly defined goals, it may well prove an uncomfortable future for humans, because artificial intelligence, while not inherently evil, will become the ultimate optimisation process.

"We may set the AI a goal to make humans smile and the super-intelligence may decide that the best way to do this would be to take control of the world and stick electrodes in the cheeks of all humans.

"Or we may set it a tough mathematical problem to solve and it may decide the most effective way to solve it is to transform the planet into a giant computer to increase its thinking power," he said during his talk.

Not yet

Ask an expert in AI when the robots will take over the world and they are likely to give you a wry smile.

For IBM's head of research, Guru Banavar, AI will work with humans to solve pressing problems such as disease and poverty.

While Geoff Hinton, known as the godfather of deep learning, also told the BBC that he "can't foresee a Terminator scenario".

"We are still a long way off," although, he added, not entirely reassuringly: "in the long run, there is a lot to worry about."

The reality is that we are only at the dawn of AI and, as Prof Hinton points out, attempting to second-guess where it may take us is "very foolish".

"You can see things clearly for the next few years but look beyond 10 years and we can't really see anything - it is just a fog," he said.

Computer-based neural networks, which mimic the brain, are still a long way from replicating what their human counterparts can achieve.

"Even the biggest current neural networks are hundreds of times smaller than the human brain," said Prof Hinton.

What machines are good at is taking on board huge amounts of information and making sense of it in a way that humans simply can't do, but the machines have no consciousness, don't have any independent thought and certainly can't question what they do and why they are doing it.

As Andrew Ng, chief scientist at Chinese e-commerce site Baidu, puts it: "There's a big difference between intelligence and sentience. Our software is becoming more intelligent, but that does not imply it is about to become sentient."

AI may be neutral - but as author James Barrat points out in his book, Our Final Invention, that does not mean it can't be misused.

"Advanced AI is a dual-use technology, like nuclear fission. Fission can illuminate cities or incinerate them. At advanced levels, AI will be even more dangerous than fission and it's already being weaponised in autonomous drones and battle robots."

A sentry robot could, in theory, fire weapons without human intervention

Already operating on the South Korean border is a sentry robot, dubbed SGR-1. Its heat-and-motion sensors can identify potential targets more than two miles away. Currently it requires a human before it shoots the machine gun that it carries but it raises the question - who will be responsible if the robots begin to kill without human intervention?

The use of autonomous weapons is something that the UN is currently discussing and has concluded that humans must always have meaningful control over machines.

Noel Sharkey co-founded the Campaign to Stop Killer Robots and believes there are several reasons why we must set rules for future battlefield bots now.

"One of the first rules of many countries is about preserving the dignity of human life and it is the ultimate human indignity to have a machine kill you," he said.

But beyond that moral argument is a more strategic one which he hopes military leaders will take on board.

"The military leaders might say that you save soldiers' lives by sending in machines instead but that is an extremely blinkered view. Every country, including China, Russia and South Korea is developing this technology and in the long run, it is going to disrupt global security," he said.

"What kind of war will be initiated when we have robots fighting other robots? No-one will know how the other ones are programmed and we simply can't predict the outcome."

Isaac Asimov wrote his rules for fiction but they may hold true for reality too

We don't currently have any rules for how robots should behave if and when they start operating autonomously.

Many fall back on a simple set of guidelines devised by science fiction writer Isaac Asimov. Introduced in his 1942 short story Runaround, the three laws of robotics - taken from the fictional Handbook of Robotics, 56th edition 2058, are as follows:

A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm

A robot must obey the orders given to it by human beings, except where such orders would conflict with the first law

A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the first or second laws.

- Published21 September 2015

- Published18 September 2015

- Published17 September 2015

- Published15 September 2015

- Published16 September 2015

- Published15 September 2015

- Published12 August 2015

- Published3 August 2015