Tech Tent - High-tech polls, robot helpers

- Published

Stream or download, external the latest Tech Tent podcast

Listen to previous episodes on the BBC website

Listen live every Friday at 15:00 GMT on the BBC World Service

On this week's Tech Tent we ask whether new technology can provide better ways of assessing the state of public opinion in the run-up to elections. We also meet a robot which promises to guide us around airports and we hear about a court battle between two big Silicon Valley names over self-driving car technology.

Election tech

The performance of opinion polls has been under scrutiny over the last year - and found wanting. The pollsters were confident that the Remain side would win the EU referendum and Hillary Clinton would beat Donald Trump to the US Presidency, and they were wrong.

But that seems to have sparked some interesting ideas on using alternative methods to gauge the public mood and we spoke to two technologists who think they can beat the pollsters.

Rob Lancashire at Essencient believes his company's use of natural language processing to analyse the mood on Twitter can pick up signs that elude the polls.

Now, when I was the BBC's Digital Election Correspondent back in 2010, this kind of sentiment analysis of social media was just getting going - and the results were pretty unimpressive.

One tech-based polling system claims to have already predicted the French election result

It turned out that Twitter was something of a Liberal Democrat echo chamber and the analysts vastly over-estimated the number of seats it would gain in the election.

But Mr Lancashire claims that his technology is far more sophisticated at evaluating the deeper meaning of tweets - and what they show about someone's intention to vote in a particular way. He says it spotted both the result of the EU referendum and the late swing towards Donald Trump in the US election.

And he says that the there's a flaw at the heart of what pollsters do which his approach avoids. "The trouble with asking a question is that immediately you're introducing a bias into the process," he says.

But Qriously, the other company we interview, is all about asking questions, which are posed to the vast global audience of smartphone users. It buys up advertising space to place a simple question in smartphone apps.

If someone responds, they are then presented with more queries, perhaps about their electoral preferences or about a product - Qriously's customers are mainly companies doing market research.

The founder Chris Kahler showed me a map with pulsing lights showing responses coming in from smartphone users across the UK. "It's a very simple idea," he says. "The difficult part is deciding who to serve the questions to and how to make sense of the results when you get them back."

That is where machine learning comes in, with the system teaching itself to assess the likely background of someone agreeing to take part in a survey. Like Essencient, Chris Kahler claims to have successfully predicted the outcome of the EU referendum and the US presidential election.

And his technology seems to have convinced both investors and customers. Qriously has been backed by the venture capital firm which put money behind the likes of Twitter and Oculus and it was hired a a few weeks ago to predict the results of the French presidential election.

Before the first round it put online a code which will unlock a document containing its predictions once the final result is known. The pollsters have actually done pretty well so far in assessing the mood of the French populace - let's see if this new approach can match them.

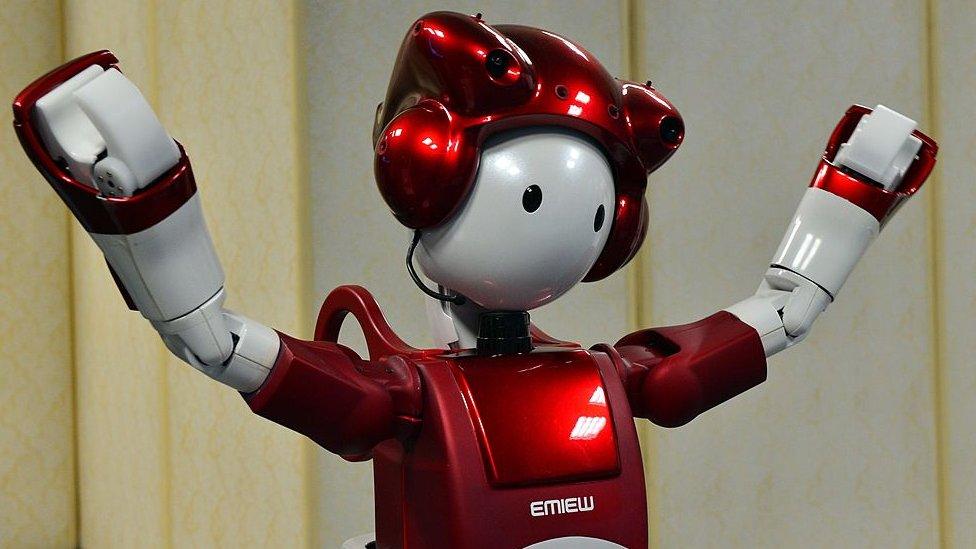

The Emiew3 robot is designed to offer assistance to people it thinks needs its help

Hitachi's Robot - Here to Help

The receptionist at Hitachi's London office greeted me in Japanese when I came to visit, but quickly switched to English when I made clear my incomprehension. This multilingual paragon was in fact a robot called Emiew, which is on its first trip to Europe,

Emiew, like Softbank's Pepper, is a friendly-looking robot designed to interact with people in a variety of customer service functions. It has been trialled at Tokyo's Haneda airport, where it has been offering information to travellers - and not just those who approach it.

The robot is connected to various surveillance cameras and its cloud-connected brain allows it to spot people who look as though they may need help and approach them. I suggested to Hitachi's design strategist Rachel Jones that in Britain some people might not like that sort of interaction.

She explained that an important part of the Emiew project was to assess different cultural attitudes to robots: "There are not just language issues but etiquette issues but I think there's a broader question for society about where we want to go and how we see robots fitting in."

During my interaction with Emiew I became bored with a lengthy explanation of the various facilities available at Hitachi's offices and interrupted rather rudely, something I certainly would not have done with a human receptionist.

Seventy-five years ago, Isaac Asimov devised his three laws of robotics - setting out how robot behaviour should be designed.

Now, as they enter more areas of our lives, we may need to update that code and include instructions for how we should behave with them.

- Published5 May 2017

- Published5 May 2017

- Published25 April 2017

- Published2 May 2017