Massive ransomware infection hits computers in 99 countries

- Published

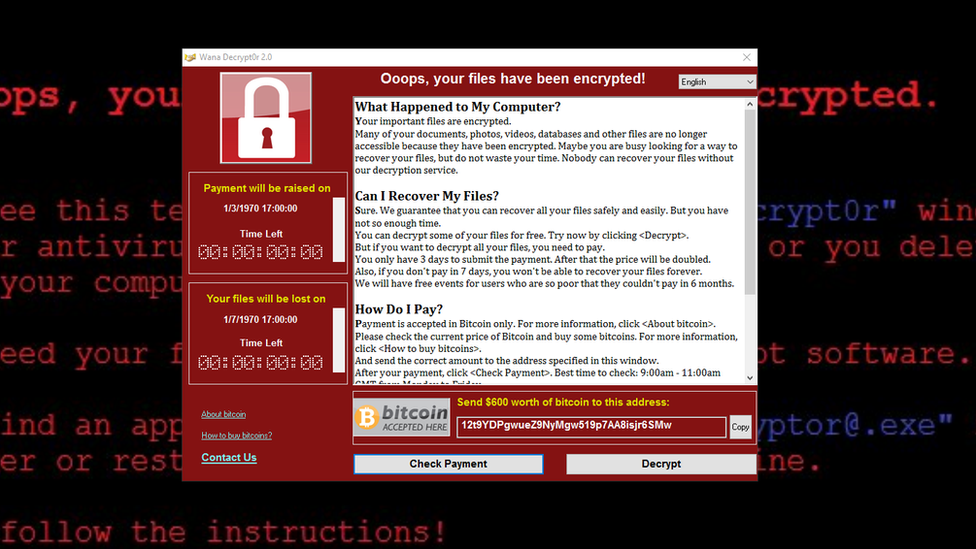

The ransomware has been identified as WannaCry - here shown in a safe environment on a security researcher's computer

A massive cyber-attack using tools believed to have been stolen from the US National Security Agency (NSA) has struck organisations around the world.

Cyber-security firm Avast said it had seen 75,000 cases of the ransomware - known as WannaCry and variants of that name - around the world.

There are reports of infections in 99 countries, including Russia and China.

Among the worst hit was the National Health Service (NHS) in England and Scotland.

The BBC understands about 40 NHS organisations and some medical practices were hit, with operations and appointments cancelled.

NHS cyber attack: "My heart surgery was cancelled"

How did the cyber-attack unfold?

The malware spread quickly on Friday, with medical staff in the UK reportedly seeing computers go down "one by one".

NHS staff shared screenshots of the WannaCry program, which demanded a payment of $300 (£230) in virtual currency Bitcoin to unlock the files for each computer.

Throughout the day other, mainly European countries, reported infections.

Some reports said Russia had seen more infections than any other single country. Domestic banks, the interior and health ministries, the state-owned Russian railway firm and the second largest mobile phone network were all reported to have been hit.

Russia's interior ministry said 1,000 of its computers had been infected but the virus was swiftly dealt with and no sensitive data was compromised.

In Spain, a number of large firms - including telecoms giant Telefonica, power firm Iberdrola and utility provider Gas Natural - were also hit, with reports that staff at the firms were told to turn off their computers.

People tweeted photos of affected computers including a local railway ticket machine, external in Germany and a university computer lab, external in Italy.

France's car-maker Renault, Portugal Telecom, the US delivery company FedEx and a local authority in Sweden were also affected.

China has not officially commented on any attacks it may have suffered, but comments on social media said a university computer lab had been compromised.

Coincidentally, finance ministers from the Group of Seven wealthiest countries have been meeting in Italy to discuss the threat of cyber-attacks on the global financial system.

They are expected to release a statement later in which they pledge greater co-operation in the fight against cyber-crime, including spotting potential vulnerabilities and assessing security measures.

The BBC's Rory Cellan Jones explains how Bitcoin works

How does the malware work and who is behind it?

The infections seem to be deployed via a worm - a program that spreads by itself between computers.

Most other malicious programs rely on humans to spread by tricking them into clicking on an attachment harbouring the attack code.

By contrast, once WannaCry is inside an organisation it will hunt down vulnerable machines and infect them too.

Some experts say the attack may have been built to exploit a weakness in Microsoft systems that had been identified by the NSA and given the name EternalBlue.

The NSA tools were stolen by a group of hackers known as The Shadow Brokers, who made it freely available in April, saying it was a "protest" about US President Donald Trump.

At the time, some cyber-security experts said some of the malware was real, but old.

A patch for the vulnerability was released by Microsoft in March, which would have automatically protected those computers with Windows Update enabled.

Microsoft said on Friday, external it would roll out the update to users of older operating systems "that no longer receive mainstream support", such Windows XP (which the NHS still largely uses), Windows 8 and Windows Server 2003.

Technology explained: what is ransomware?

The number of infections seems to be slowing after a "kill switch" appears to have been accidentally triggered by a UK-based cyber-security researcher tweeting as @MalwareTechBlog, external.

He was quoted as saying, external he noticed the web address the virus was searching for had not been registered - and when he registered it, the virus appeared to stop spreading.

But he warned this was a temporary fix, and urged computers users to "patch your systems ASAP".

Why do companies still use Windows XP? By Chris Foxx, technology reporter

Many jobs can be done using software everyone can buy, but some businesses need programs that perform very specific jobs - so they build their own.

For example. a broadcaster might need specialist software to track all the satellite feeds coming into the newsroom, and a hospital might need custom-built tools to analyse X-ray images.

Developing niche but useful software like this can be very expensive - the programming, testing, maintenance and continued development all adds up.

Then along comes a new version of Windows, and the software isn't compatible. Companies then face the cost of upgrading computers and operating system licenses, as well as the cost of rebuilding their software from scratch.

So, some choose to keep running the old version of Windows instead. For some companies, that is not a huge risk. In a hospital, the stakes are higher.

- Published13 May 2017

- Published14 May 2017

- Published12 May 2017