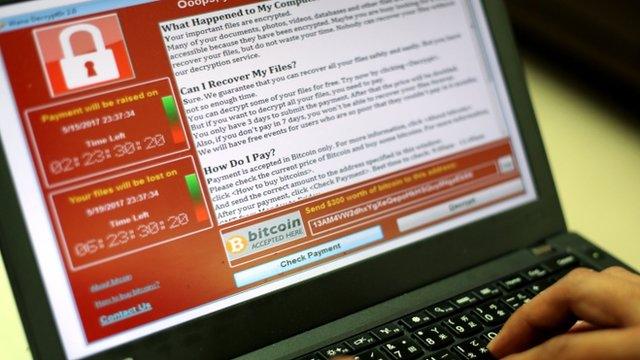

WannaCry and the malware hall of fame

- Published

The demand for Bitcoin appeared on departure screens at a Frankfurt station

2017 has been a bumper year for malware outbreaks. We had the WannaCry worm causing havoc around the world for days, followed most recently by the Petya outbreak. But they are not the first to spread so far, so fast. The history of technology and the net has been regularly punctuated by outbreaks and infections.

The Morris worm

In 1988, just as the internet was starting to catch on, computer science student Robert T Morris was curious about just how big it had grown. He wrote a small program that travelled around, logging the servers it visited.

Bugs in his code made it scan the net very aggressively so every server ended up running multiple copies of the worm. Each copy used up a little bit of processing power so the servers gradually slowed to a halt.

The scanning traffic clogged the net making it almost unusable. It took days to clean up the infection.

Mr Morris was caught and found guilty of computer fraud and was fined $10,050 (£7,785).

These days, he is a computer scientist at the Massachussetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

The Morris worm has one strange parallel with WannaCry. Mr Morris was the son of the NSA's chief scientist and the WannaCry worm is based on code stolen from the NSA.

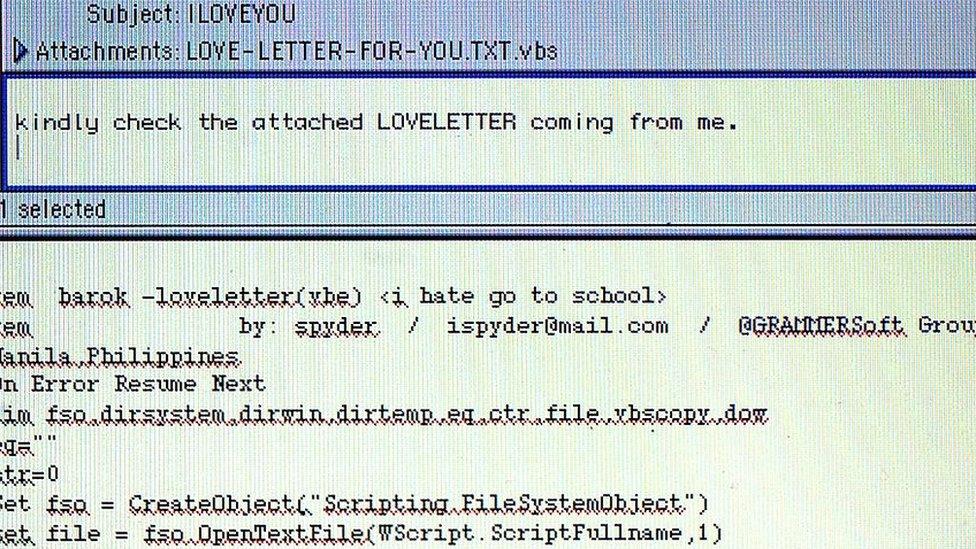

ILOVEYOU

Unromantic.

In May 2000, millions of Windows users found endless copies of an email bearing the subject line ILOVEYOU in their inboxes.

It spread so far and so fast thanks to the booby-trapped file attached to it. Opening the file fired up the small program it contained which sent a copy of the same message to all the addresses found in a victim's address book.

It was also helped to spread because all those messages appeared to come from someone a recipient knew. And the subject line made people curious too.

ILOVEYOU rattled around the world for almost two weeks racking up more than 50 million infections. High-profile victims included the CIA, Pentagon and UK Parliament.

Philippine students Reonel Ramones and Onel de Guzman were found to be the creators of ILOVEYOU. They escaped prosecution because there were no computer misuse laws in the Philippines at that time.

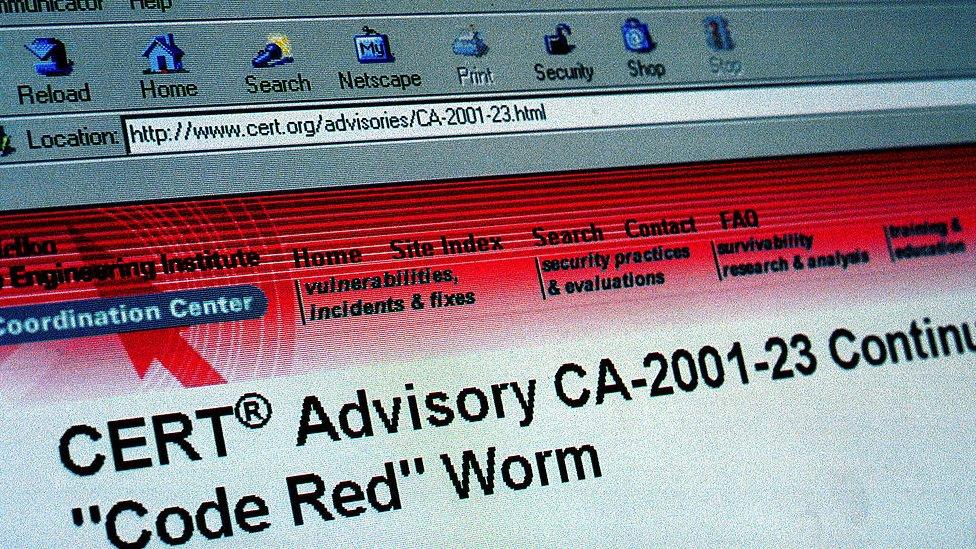

Code Red

A warning about the worm was issued at Carnegie Mellon University

Active in July 2001 and named after the fizzy pop being drunk by the researchers who found it, this worm targeted web servers running Microsoft IIS software.

It caused severe disruption and many websites, small businesses and larger firms were knocked offline for a while.

No-one has ever been named as Code Red's creator although on servers it compromised it displayed a message suggesting it originated in China.

Like Wannacry, Code Red exploited a known bug and caught out servers that had not been updated with a patch.

SQL Slammer

This internet cafe in South Korea was practically empty after an SQL Slammer infection in 2003

This worm emerged in January 2003 and was so virulent that it is believed to have slowed down traffic across the entire net as it spread.

Slammer was a tiny program, roughly 376 bytes, that did little more than create random net addresses and then send itself to those places. If it hit a machine running a vulnerable version of Microsoft's SQL server, that machine got infected and then started spraying out more copies seeking more victims.

The slowdown was caused by net routers struggling to cope with the massive amounts of traffic Slammer generated while seeking out new hosts.

Again, a patch was available for the bug it exploited but many people had not applied it despite it being available for six months.

MyDoom

This Windows email worm from January 2004 is believed to hold the current record for spreading fastest - hardly surprising given that it was reputedly created by professional spammers.

It worked so well thanks to a clever bit of social engineering. The email bearing the worm was designed to look like an error message. This fiction was aided by the message's attachment which purported to hold a copy of the email that did not arrive.

Opening the attachment kicked off the malicious code that re-sent the same message to everyone in a victim's address book.

Conficker

November 2008 saw the arrival of this virulent worm which hit up to 15 million servers running Microsoft software. It ran rampant and caught out hospitals, governments, the armed forces and many businesses.

The outbreak was so bad that Microsoft offered a $250,000 reward for any information leading to the identification of the worm's creator. No-one has ever been identified as its originator.

A patch closing the loophole it exploited was released by Microsoft about a month after it appeared. Even today, 10 years on, data traffic generated by machines infected with Conficker regularly turn up.

- Published15 May 2017

- Published15 May 2017

- Published15 May 2017

- Published16 May 2017

- Published23 May 2017

- Published19 May 2017