General election 2017: Workers' rights v robo jobs - a quandary for all campaigns

- Published

Lee Hayhow has worked as a lorry driver for five years

Clever computers that learn on the job could recast Britain's job market - for better or worse. What are the parties vying for power in the general election saying on the subject?

Twenty-nine-year-old Lee Hayhow is the third generation of his family to work as a lorry driver, following his father and grandfather.

He is proud of his job.

"I've always enjoyed lorries and driving. I trained as a professional driver. It is a profession.

"You're almost your own boss - in charge of that vehicle. I always do it to the best of my ability. It's a good feeling."

He estimates it costs £3,000 to train as a heavy goods vehicles (HGVs) driver. Mr Hayhow's employer, O'Donovan Waste Disposal, paid for this, but not all firms do, he says.

And he would be delighted to see the next generation of Hayhows - his two young daughters - follow his career path.

But by then, the decision may not be theirs to take.

Call centres to catering

Lorry driving, like many other jobs that help power the British economy, could be facing a huge shake-up.

Advances in artificial intelligence (AI) - a field of computer science in which machines are taught to carry out tasks that require human traits of thought or intelligence - have led some to predict a knock-on catastrophe for jobs.

Nowhere is the exponential growth of AI more apparent than in the race towards self-driving vehicles.

But AI doesn't stop at transport. There have been stark warnings about its impact on the jobs market as computer programs are honed to perform a number of roles, including call centre work, banking and paralegal responsibilities, retail and catering tasks, and journalism.

Up to 46% of jobs in Scotland could be at risk within the next decade, the Institute for Public Policy Research Scotland recently claimed. Accountancy firm PwC predicted 30% of existing jobs in the UK could be "at high risk of automation" by the 2030s.

Calum Chace, author of Surviving AI and the Economic Singularity, foresees "quite a lot" of unemployment caused by the takeover of technology "in a decade and a lot in two decades".

"The industrial revolution was mechanisation and humans had something else to offer - cognitive skills. This time around machines are coming for our cognitive jobs," said Mr Chace.

Others, though, predict a huge economic dividend. Consultants Accenture estimated AI could add about of £654bn to the UK economy by 2035.

One influential voice talks of old jobs making way for new ones. But these new occupations cannot be taken for granted.

"The absolute nightmare for me would be that we're applying this technology, we're displacing jobs as a result of it - which will happen - but what we're not doing at the same time is creating all the jobs in computer science, in data analytics, in software code writing," said Juergen Maier, chief executive of Siemens UK, in an interview with the Guardian, external.

All of which leaves Britain's next government with a quandary - continue to invest heavily to support Britain's fledgling AI industries, in the belief they will foster greater efficiency and productivity, and new jobs, or safeguard the rights of existing workers?

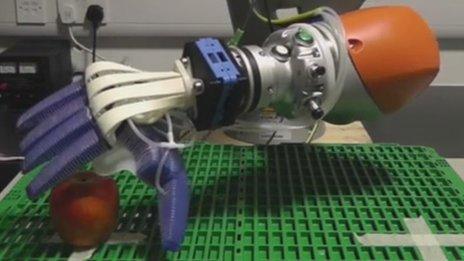

Online grocer Ocado is developing a humanoid maintenance technician to supervise its warehouses

Thanks to the general election manifestos of those vying to take power on 8 June, it's possible to get an idea of how primed our politicians are for the AI future.

In its 2017 manifesto the Conservative Party asserts Britain is "leading the world in preparing for autonomous vehicles," although in reality others are further ahead.

The Lib Dems note the "advent of robotics and increasing artificial intelligence will also change the nature of work for many people". They say the government "needs to act now to ensure this technological march can benefit everyone and that no areas are left in technology's wake".

Its solution is to provide more support for digital skills training and businesses/tech hubs in the sector.

Industry in denial

The Conservatives also commit to establishing "institutes of technology" and pledge to a long-term goal of investing 3% of the UK's GDP in research and development.

Labour's Tom Watson, Shadow Secretary of State for Culture and Media, told the BBC there is "no doubt" automation and AI will "change most people's jobs".

In response, he has set up an independent Future of Work Commission which is due to report in the autumn.

"We want to understand the implications of new technology on work and make achievable recommendations about the most pressing challenges and opportunities of the future," he said.

UKIP's manifesto doesn't mention AI or automation, although it has pledged to scrap tuition fees for degrees in technology, engineering and mathematics. The SNP's manifesto had not been published at time of writing and it did not respond to a request for comment.

However there is considerable denial about the AI revolution among some of the workers potentially on the frontline - not least the lorry drivers.

One of the convoys of automated lorries which took part in the 2016 European Platooning Challenge

Despite the apparent success of the European Truck Platooning Challenge, external in March last year, in which convoys of automated lorries (with humans on board just in case) drove from Sweden, Germany and Belgium to Rotterdam in Holland, the Road Haulage Association said its members were "deeply sceptical" about whether driverless lorries would arrive on the roads in the next 10 years.

Despite this, Jack Semple, director of policy, admitted "if it works, particularly in HGVs, there is huge potential for savings.

"You eliminate not only driver costs but also the restrictions on vehicle movement that come from drivers' hours regulations."

Lee Hayhow isn't concerned.

"It's too intricate, the job that we do," he said.

Calum Chace fears that people who share Mr Hayhow's views are in for a shock.

"When they start seeing cars driving around with no one driving them, people will realise how impressive computers are," he said.

"If we don't have a plan, people will panic."

- Published26 April 2017

- Published25 April 2017

- Published17 April 2017

- Published31 January 2017