Rise of the robots: What advances mean for workers

- Published

It's about the size and shape of a photocopier.

Emitting a gentle whirring noise, it travels across the warehouse floor while two arms raise or lower themselves on scissor lifts, ready for the next task.

Each arm has a camera on its knuckle. The left one eases a cardboard box forward on the shelf, the right reaches in and extracts a bottle.

Like many new robots, it's from Japan. Hitachi showcased it in 2015 and hopes to be selling it by 2020.

Find out more

50 Things That Made the Modern Economy highlights the inventions, ideas and innovations which have helped create the economic world we live in.

It is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

It's not the only robot that can pick a bottle off a shelf - but it's as close as robots have yet come to performing this seemingly simple task as speedily and dextrously as a good old-fashioned human.

One day, robots like this might replace warehouse workers altogether.

For now, humans and machines run warehouses together.

There are already 45,000 Kiva robots at work in Amazon warehouses

In Amazon depots, Kiva robots scurry around, not picking things off shelves, but carrying the shelves to humans for them to select things.

In this way, Kiva robots can improve efficiency up to fourfold.

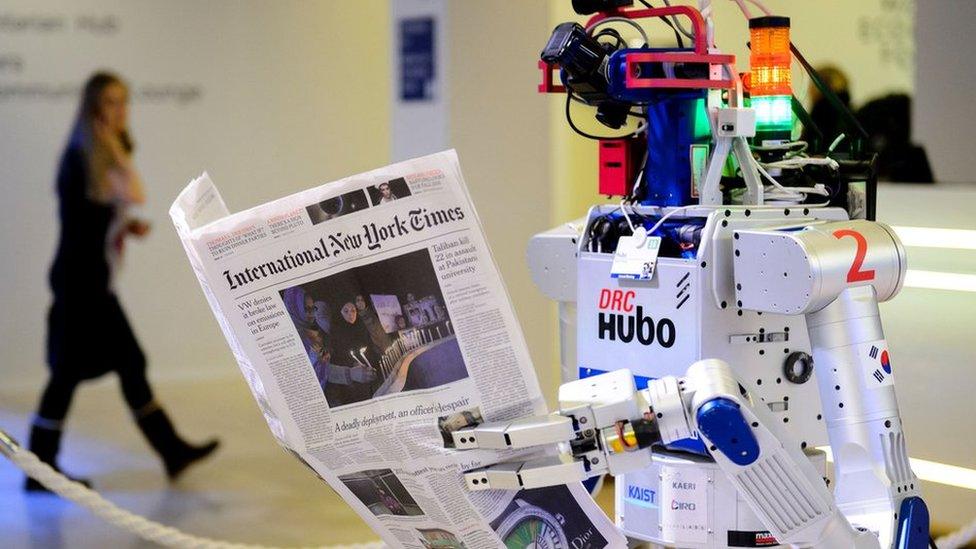

Robots and humans work side-by-side in factories, too.

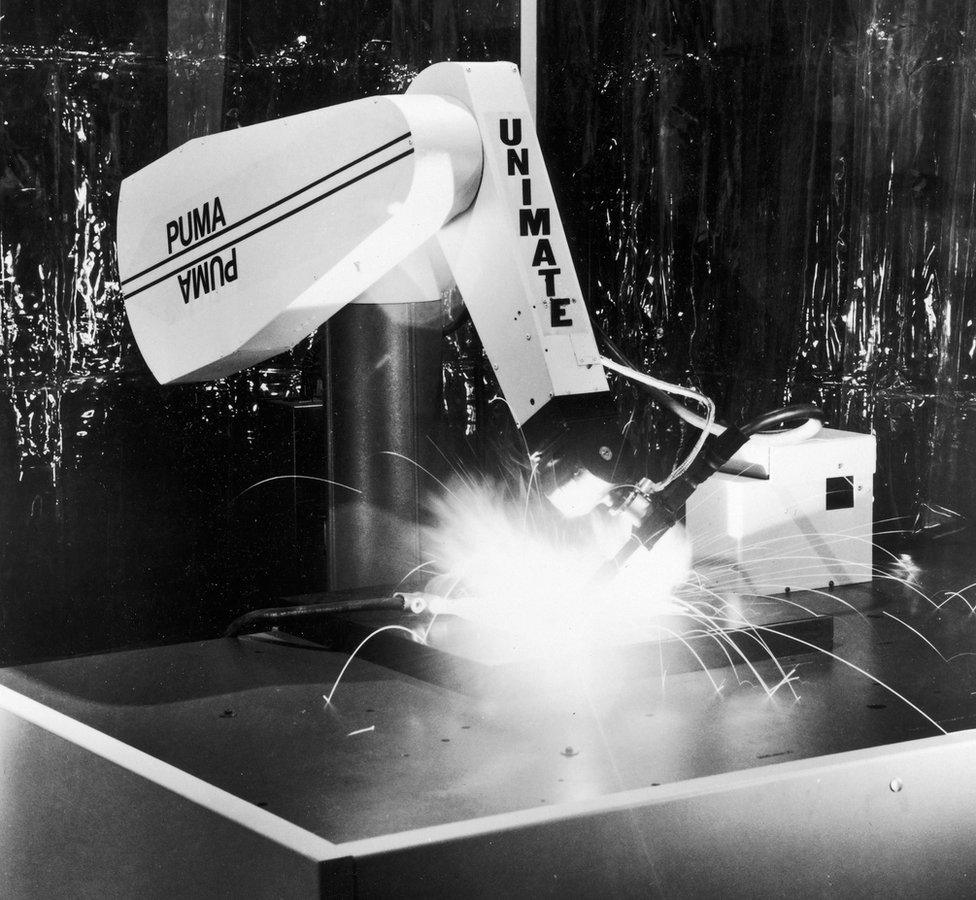

Factories have had robots since 1961, when General Motors installed the first Unimate, a one-armed automaton that was used for tasks like welding.

But until recently, robots were strictly segregated from human workers - partly to protect the humans, and partly to stop them confusing the robots, whose working conditions had to be strictly controlled.

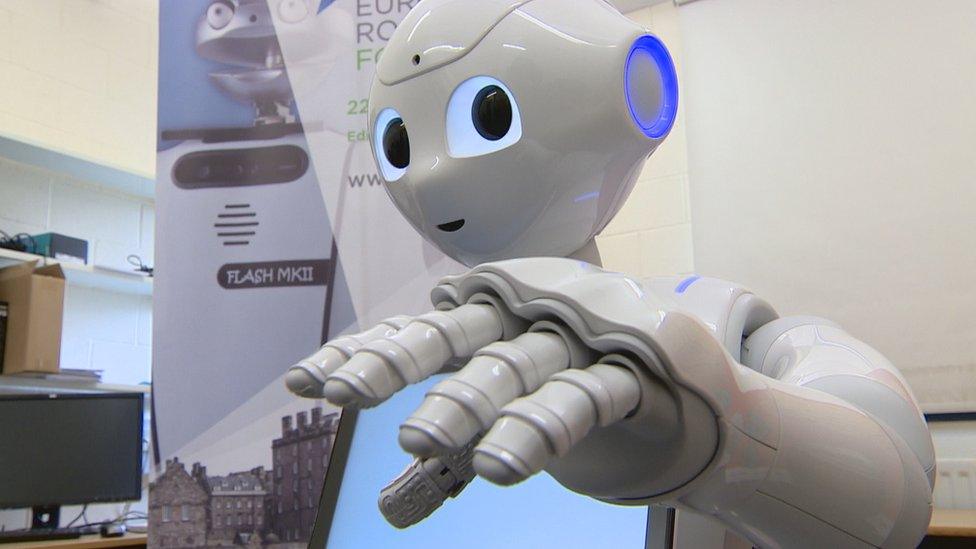

With some new robots, that's no longer necessary.

Take Rethink Robotics' Baxter.

'Reshoring' trend

Baxter can generally avoid bumping into humans, or falling over if humans bump into it. Cartoon eyes indicate to human co-workers where it's about to move.

Baxter can learn new tasks from its co-workers

Historically, industrial robots needed specialist programming, but Baxter can learn new tasks from its co-workers.

The world's robot population is expanding quickly - sales of industrial robots are growing by around 13 per cent a year, meaning the robot "birth rate" is almost doubling every five years.

There has long been a trend to "offshore" manufacturing to cheaper workers in emerging markets. Now, robots are part of the "reshoring" trend that is returning production to established centres.

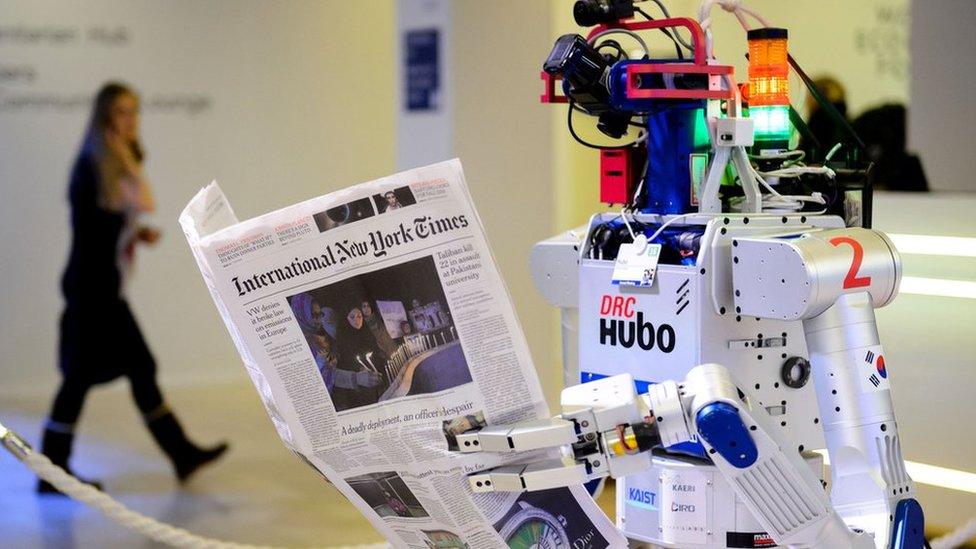

They do more and more things - they're lettuce-pickers, bartenders, hospital porters.

But they're still not doing as much as we'd once expected.

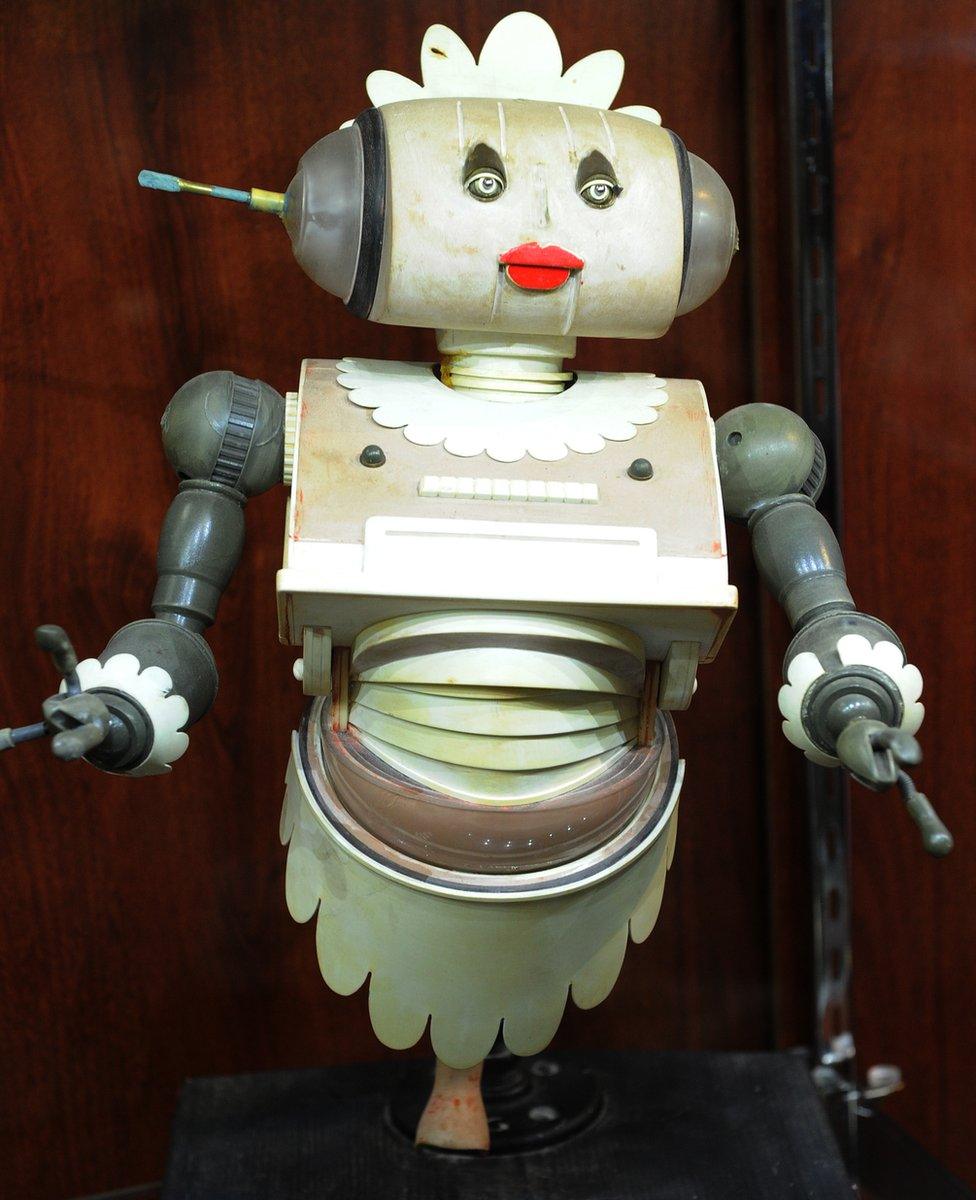

In 1962 - a year after the Unimate was introduced - the American cartoon The Jetsons imagined Rosie, a robot maid doing all the household chores. That prospect still seems remote.

We're still waiting for Rosie the Robot to run our homes as predicted

The progress that has happened is partly thanks to improved robot hardware, including better and cheaper sensors - essentially improving a robot's eyes, the touch of its fingertips, and its balance.

But it's also about software: robots are getting better brains.

And it's about time, too. Machine thinking is another area where initial high expectations encountered early disappointments.

Attempts to invent artificial intelligence are generally dated to 1956, and a summer workshop at Dartmouth College for scientists with a pioneering interest in "machines that use language, form abstractions and concepts, solve kinds of problems now reserved for humans, and improve themselves".

More from Tim Harford

Then, machines with human-like intelligence were thought to be about 20 years away.

Now, they're thought to be… about 20 years away.

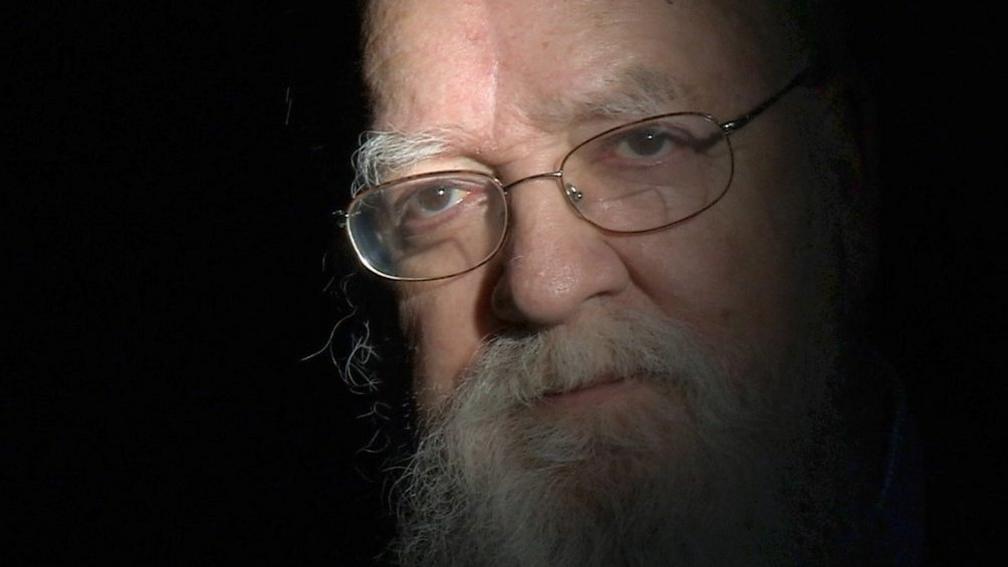

The futurist philosopher Nick Bostrom has a cynical take on this.

Self-improvement = superintelligence?

Twenty years is "a sweet spot for prognosticators of radical change", he writes. Nearer, and you would expect to be seeing prototypes by now. Further away is not so attention-grabbing.

It's only in the last few years that progress in artificial intelligence (AI) has really started to accelerate.

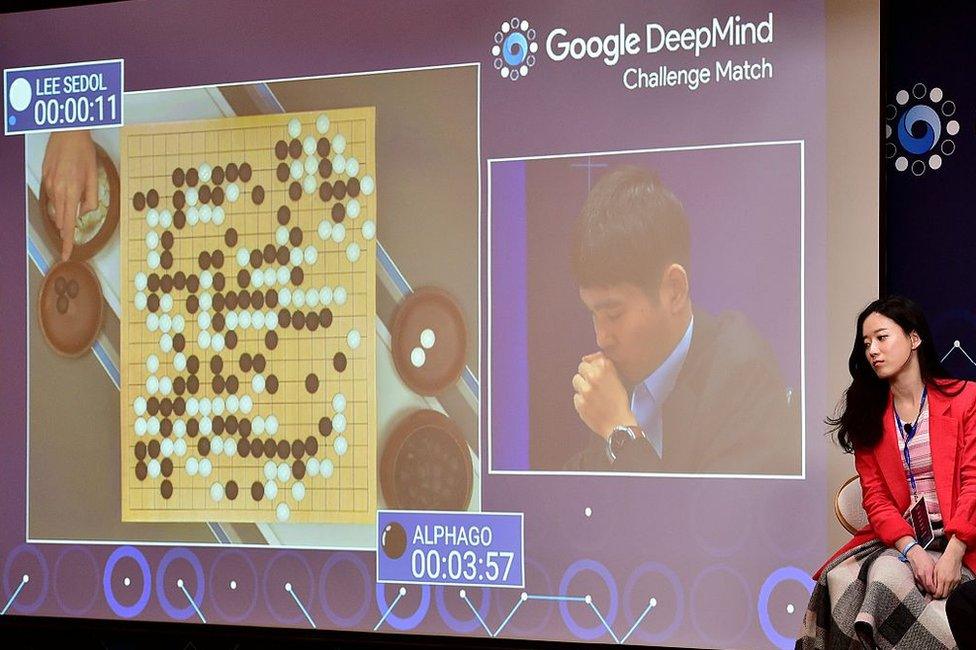

Specifically, in what's known as narrow AI - algorithms that can do one thing very well, like playing Go, or filtering email spam, or recognising faces in your Facebook photos.

Google's AlphaGo beat South Korean Go grandmaster Lee Se-Dol 4-1 in March 2016

Processors have become faster, data sets bigger, and programmers better at writing algorithms that can learn how to improve themselves.

That capacity for self-improvement worries some thinkers like Bostrom. What will happen if and when we create artificial general intelligence - a system which could apply itself to any problem, as humans can?

Will it rapidly turn itself into a superintelligence? How would we keep it under control?

That's not an imminent concern, at least. Human-level artificial general intelligence is still about, ooh, 20 years away.

But narrow AI is already transforming the economy.

For years, algorithms have been taking over white-collar drudgery in areas like book-keeping and customer service. And more prestigious jobs are far from safe.

Watson's Jeopardy! victory over leading contestants Ken Jennings and Brad Rutter was the culmination of a four-year research project

IBM's Watson, which hit the headlines for beating human champions at the game show Jeopardy!, is already better than doctors at diagnosing lung cancer.

Software is getting to be as good as experienced lawyers at predicting what lines of argument are most likely to win a case.

'Secular stagnation'

Robo-advisers dispense investment advice.

Algorithms routinely churn out news reports on the financial markets and sports - although, luckily for me, it seems they can't yet write feature articles about technology and economics.

Some economists reckon robots and AI explain a curious economic trend.

The BBC's quick guide to Artificial Intelligence

Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee argue there's been a "great decoupling" between jobs and productivity - how efficiently an economy takes inputs, like people and capital, and turns them into useful stuff.

Historically, better productivity meant more jobs and higher wages.

But Brynjolfsson and McAfee argue that's no longer the case in the United States. Since the turn of the century, US productivity has been improving, but jobs and wages haven't kept pace.

Some economists worry that we're experiencing "secular stagnation" - where there's not enough demand to spur economies into growing, even with interest rates at or below zero.

Technology destroying jobs is nothing new - it's why, 200 years ago, the Luddites went around destroying technology.

"Luddite" has become a term of mockery because technology has always, eventually, created new jobs to replace the ones it destroyed. Better jobs. Or at least, different jobs.

What happens this time remains debatable. It's possible that some of the jobs humans will be left doing will actually be worse.

The Jennifer Unit is a voice-directed computer application which tells workers how best to carry out their tasks

That's because technology seems to be making more progress at thinking than doing: robots' brains are improving faster than their bodies.

Martin Ford, author of Rise Of The Robots, points out that robots can land aeroplanes and trade shares on Wall Street, but still can't clean toilets.

So perhaps, for a glimpse of the future, we should look not to Rosie the Robot but to another device now being used in warehouses: the Jennifer Unit.

It's a computerised headset that tells human workers what to do, down to the smallest detail.

If you have to pick 19 identical items from a shelf, it'll tell you to pick five, then five, then five, then four. That leads to fewer errors than saying "pick 19".

If robots beat humans at thinking, but humans beat robots at picking things off shelves, why not control a human body with a robot brain?

It may not be a fulfilling career choice, but you can't deny the logic.

Tim Harford writes the Financial Times's Undercover Economist column. 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

- Published24 March 2017

- Published20 March 2017

- Published1 March 2017

- Published1 March 2017

- Published7 February 2017

- Published3 February 2017

- Published5 January 2017

- Published11 September 2015