Is it dangerous for humans to depend on computers?

- Published

In the last week, we have seen the best and worst of computer technology.

In China, Google's DeepMind artificial intelligence program took on and beat the world champion of the complex game of Go, reducing him to tears. Nineteen-year-old Ke Jie described the AI computer as "perfect, flawless, without any emotions".

But in airports in the UK and elsewhere last weekend tears were also being shed over computers.

In this case, though, the primary emotions were frustration and rage over the chaos caused when British Airways' IT system collapsed, leaving thousands of passengers going nowhere and their baggage stuck they knew not where.

What is striking about both these cases is how difficult human beings found it to explain exactly what was happening inside the brains of the computers.

British Airways' IT system collapse saw many passengers, and their baggage, grounded

DeepMind's AlphaGo is largely self-taught - it was shown the basic rules of Go and then it spent time looking at millions of games and playing against itself, coming up with moves that astounded professional players and its creators.

BA's computers were not so smart. The company says its problems began when there was a power surge at a data centre at Heathrow Airport in London.

That shouldn't have been more than a temporary hitch - in fact one expert told me it should not have even set the lights blinking at the data centre - but it seems to have triggered a chain reaction which took out the entire system.

That meant the sea of complex data about passengers, baggage and aircraft movements was effectively frozen - and it took 48 hours to unfreeze it and get the airline working again.

Any major organisation is likely to have both a backup system to switch to when things go wrong and a disaster recovery plan, which should be rehearsed on a regular basis. But in British Airways' case neither appears to have worked as it should.

The trade unions blame cost-cutting and the fact that BA outsourced much of its IT operation to India last year.

Computers have revolutionised the world but are not flawless

The bosses deny that and say they are now clear what went wrong - but so far, have been unable to give an explanation that seems satisfactory to people with expertise in how data centres and major IT operations work.

But what is clear is that ever more areas of our lives are dependent on vast computer systems, often now hosted in data centres owned by companies like Amazon and Microsoft.

These systems have become essential to industries from banking to travel to healthcare and they are helping them become more efficient - sometimes by getting much of the work done in countries like India where costs are lower.

They are also making life better in all sorts of ways - just think of how time-consuming it used to be to book a flight or apply for a place at university and how much paper was involved.

But now we are beginning to find out just how helpless we feel when, for whatever reason, the computers fail.

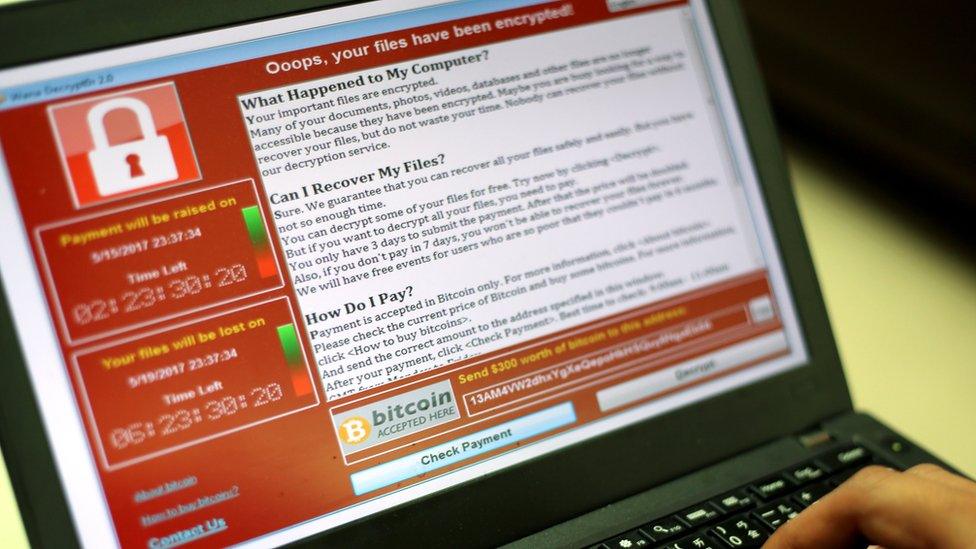

Recent cyber-attacks have highlighted potential security problems in computer networks

In Britain, doctors whose computers froze during the recent ransomware attack had to turn patients away. In Ukraine, there were power cuts when hackers attacked the electricity system, and five years ago, millions of Royal Bank of Scotland customers were unable to get at their money for days after problems with a software upgrade.

Already some people have had enough. This week a letter to the Guardian newspaper warned that the modern world was "dangerously exposed by this reliance on the internet and new technology".

The correspondent, quite possibly a retired government employee, continued "there are just enough old-time civil servants left alive to turn back the clock and take away our dangerous dependence on modern technology."

Somehow, though, I don't see this happening. Airlines are not going to scrap the computers and tick passengers off on a paper list before they climb aboard, bank clerks will not be entering transactions in giant ledgers in copperplate writing.

In fact, computers will take over more and more functions once restricted to humans, most of them far more useful than a game of Go. And that means that at home, at work and at play we will have to get used to seeing our lives disrupted when those clever machines suffer the occasional nervous breakdown.

- Published25 May 2017

- Published28 May 2017