Cyber-attack was about data and not money, say experts

- Published

Companies and organisations in Ukraine were hit hard by the Petya variant

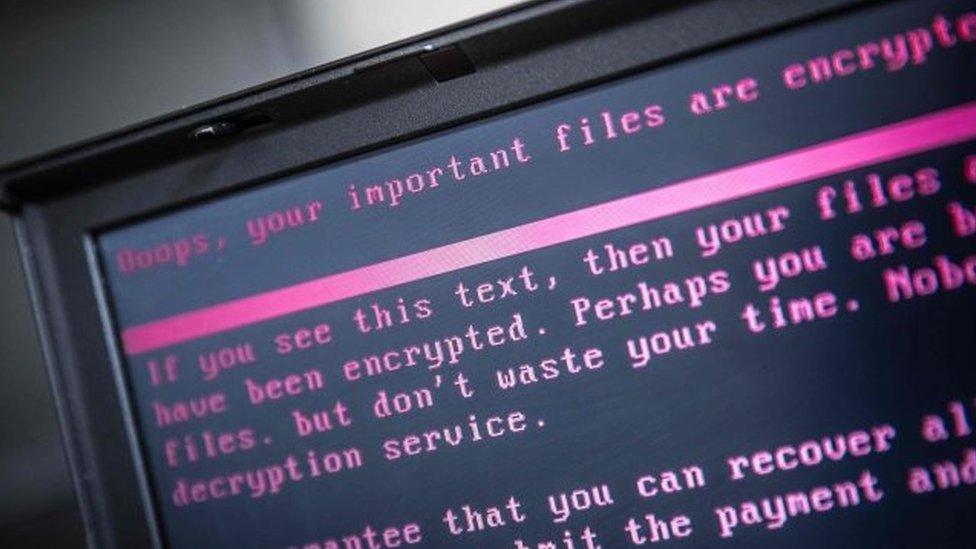

The Petya malware variant that hit businesses around the world may not have been an attempt to make money, suspect security experts.

The malicious program demanded a payment to unlock files it scrambled on infected machines.

However, a growing number of researchers now believe the program was launched just to destroy data.

Experts point to "aggressive" features of the malware that make it impossible to retrieve key files.

Cashing out

Matt Suiche, from security firm Comae, described the variant as a "wiper" rather than straight-forward ransomware.

"The goal of a wiper is to destroy and damage," he wrote, adding that the ransomware aspect of the program was a lure to generate media interest.

Although the Petya variant that struck this week has superficial similarities to the original virus, it differs in that it deliberately overwrites important computer files rather than just encrypting them, he said.

Mr Suiche wrote: "2016 Petya modifies the disk in a way where it can actually revert its changes, whereas, 2017 Petya does permanent and irreversible damages to the disk."

Anton Ivanov and Orkhan Mamedov from Russian security firm Kaspersky Lab, external agreed that the program was built to destroy rather than generate funds.

"It appears it was designed as a wiper pretending to be ransomware," they said.

Their analysis of the malware revealed that it had no way to generate a usable key to decrypt data.

"This is the worst case news for the victims," they said. "Even if they pay the ransom they will not get their data back."

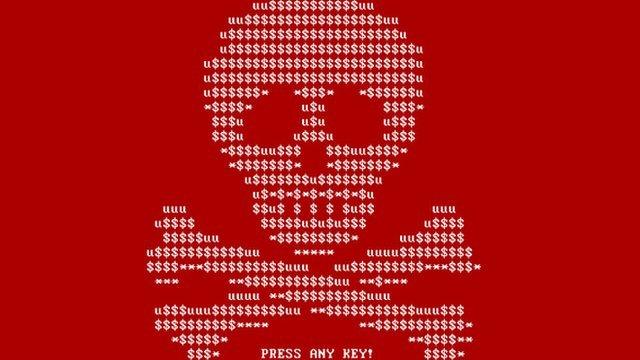

The original Petya ransomware made a computer unusable until a ransom was paid

A veteran computer security researcher known as The Grugq said the, external "poor payment pipeline" associated with the variant lent more weight to the suspicion that it was more concerned with data destruction than cashing out.

"The real Petya was a criminal enterprise for making money," he wrote. "This is definitely not designed to make money."

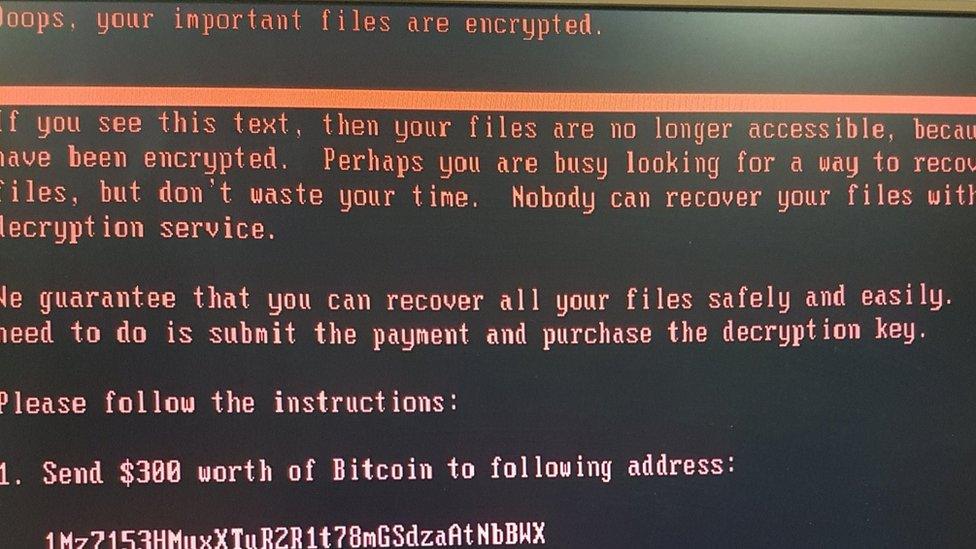

The Bitcoin account associated with the malware has now received 45 payments from victims who have paid more than $10,000 (£7,785) into the digital wallet.

The email account through which victims are supposed to report that they have paid has been closed by the German firm hosting it - closing off the only supposed avenue of communication with the malware's creators.

Remote controls

Organisations in more than 64 countries are now known to have fallen victim to the malicious program.

The latest to come forward is voice-recognition firm Nuance. In a statement it said, external "portions" of its internal network had been affected by the outbreak. It said it had taken measures to contain the the threat and was working with security firms to rid itself of the infection.

The initial infection vector seems to be software widely used in Ukraine to handle tax payments and about 75% of all infections caused by this Petya variant have been seen in the country.

A Cadbury factory in Australia halted production while it dealt with problems caused by the Petya malware variant

A government spokesman for Ukraine blamed Russia for starting the attack.

"It's difficult to imagine anyone else would want to do this," Roman Boyarchuk, head of Ukraine's cyber-protection centre told technology magazine Wired, external.

Computer security researcher Lesley Carhart said, external the malware hit hard because of the way it travelled once it evaded digital defences.

Ms Carhart said the malware abused remote Windows administration tools to spread quickly across internal company computer networks.

"I'm honestly a little surprised we haven't seen worms taking advantage of these mechanisms so elegantly on a large scale until now," she wrote.

Using these tools proved effective, she said, because few organisations police their use and, even if they did, acting quickly enough to thwart the malware would be difficult.

The success of the Petya variant would be likely to encourage others to copy it, she warned.

"Things are going to get worse and the attack landscape is going to deteriorate," said Ms Carhart.

How does the new ransomware spread?

Typically ransomware spreads via email, with the aim of fooling recipients into clicking on malware-laden files that cause a PC's data to become scrambled before making a blackmail demand.

But other ransomware, including Wannacry, has also spread via "worms" - self-replicating programs that spread from computer to computer hunting for vulnerabilities they can exploit.

The current attack is thought to have worm-like properties.

Several experts believe that one way it breaches companies' cyber-defences is by hijacking an automatic software updating tool used to upgrade an tax accountancy program.

Once it has breached an organisation, it uses a variety of means to spread internally to other computers on the same network.

One of these is via the so-called EternalBlue hack - an exploit thought to have been developed by US cyber-spies, which takes advantage of a weakness in a protocol used to let computers and other equipment talk to each other, known as the Server Message Block (SMB).

Another is to steal the credentials of IT staff and then make use of two administrative tools - PsExec, a program that allows software installations and other tasks to be carried out remotely, and WMIC (Windows Management Instrumentation Command-line) a program that lets

PCs to be controlled by typing in commands rather than via a graphical-interface.

Once a PC is infected, the malware targets a part of its operating system called the Master File Table (MFT).

It is essential for the system to know where to find files on the computer.

The advantage of doing this rather than trying to encrypt everything on the PC is the task can be achieved much more quickly.

Then, between 10 and 60 minutes later, the malware forces a computer to reboot, which then informs the user it is locked and requires a payment from them to get a decryption key.

- Published28 June 2017

- Published28 June 2017

- Published23 June 2017

- Published16 May 2017

- Published11 April 2016