Bodyhackers: Bold, inspiring and terrifying

- Published

WATCH: The bodyhackers enhancing the human form

Jesika Foxx has permanently purple eyeballs, and an elf-like ear. Her husband, Russ, has a pair of horns under his skin.

Stelarc, a 72-year-old Australian, has an ear on his arm. Soon he hopes to attach a small microphone to it so people can, via the internet, listen to whatever it hears.

Meow-Ludo Disco Gamma Meow-Meow - yes, that's his legal name - has the chip from his Sydney travel card implanted into his hand.

I met all these people during BodyHacking Con, in Austin, Texas.

Over the past three years, the event has become something of a pilgrimage for those involved in the biohacking scene - a broad spectrum of technologists, trans-humanists and performance artists. This year it also attracted the presence of the US military.

And, as I'd find out before I left, it has opened its doors to reckless opportunists.

What is bodyhacking?

The convention's organisers defined the pursuit, external as actively changing one's body or mind to better reflect a person's belief of what their "ideal self" would be.

This can range from meditation or cosmetic surgery to placing radio-transmitting tags beneath the skin or taking brain-altering drugs.

In theory, weightlifting, pilates and even just wearing a fitness tracker counts.

But the term is more commonly associated with more unusual efforts.

'Try and blend in'

The bodyhacking community exists in a legal grey area.

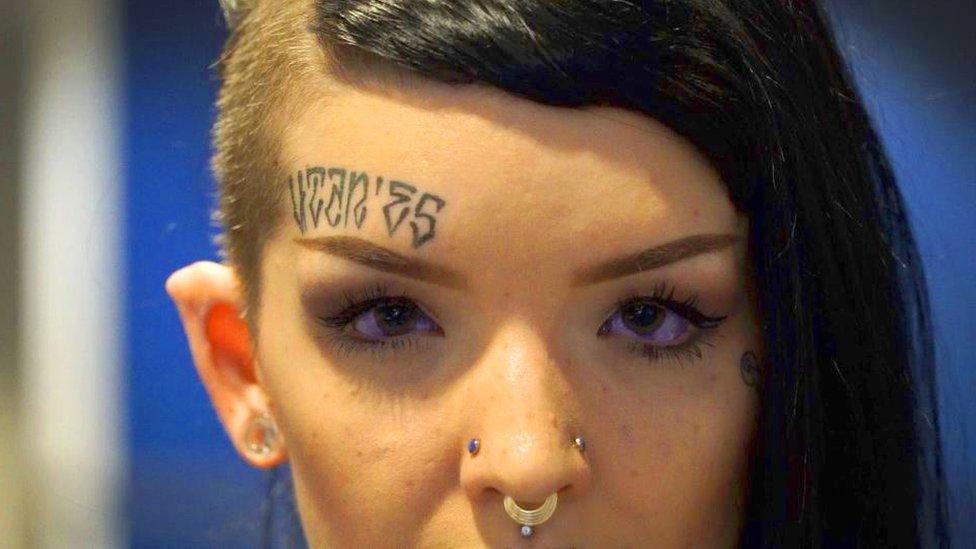

Jesika Foxx's ear and eye alterations are permanent, she says

Enthusiasts attempt to work around current laws while regulators turn a blind eye - at least until they figure out how to handle the growing subculture.

Everyone here has a vision of what it means to be a better, improved human. Rarely are two visions the same.

"I've been a one-handed person my whole life," said Angel Giuffria, an actress with a striking, personalised bionic arm.

"Older prosthetics were all made to try and blend in. I never really cared about hiding it, but that was the only option."

Now, you can't miss it.

"It's me. I kind of like the idea my arm can match my personality by adding lights and colours and matching it to my outfit. Things like that."

In contrast, Rich Lee, who gave the opening talk at the event, outlined his plan for men to have a small device implanted near the penis.

Its purpose? To make it vibrate.

Verge of impossible

The US military's Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (Darpa) has a solid track record of creating the next big thing.

Self-driving cars began as a Darpa project, as did GPS and, most famously of all, the internet.

Now it's looking at bodyhacking. Dr Justin Sanchez is the director of its Biological Technologies Office and he told the BBC: "If something is on the verge of being impossible, we will start exploring that area."

We don't know the full extent of Darpa's bodyhacking programme.

But publicly at least, Dr Sanchez is focusing on restorative techniques - helping improve memory and giving people suffering from paralysis the ability to control equipment with their brainwaves.

One project displayed on screen showed an elderly patient struggling to remember a list of 12 words.

"With direct brain stimulation they were able to recall those words in almost a seamless fashion," said Dr Sanchez.

Many people within the bodyhacking community have a disability

"All 12 words in rapid succession. That was a big breakthrough for us.

"Part of coming to this meeting is sharing our knowledge on all of this with a community that's very much on the leading edge."

Pancreatic progress

One of the people I particularly wanted to meet was Dana Lewis.

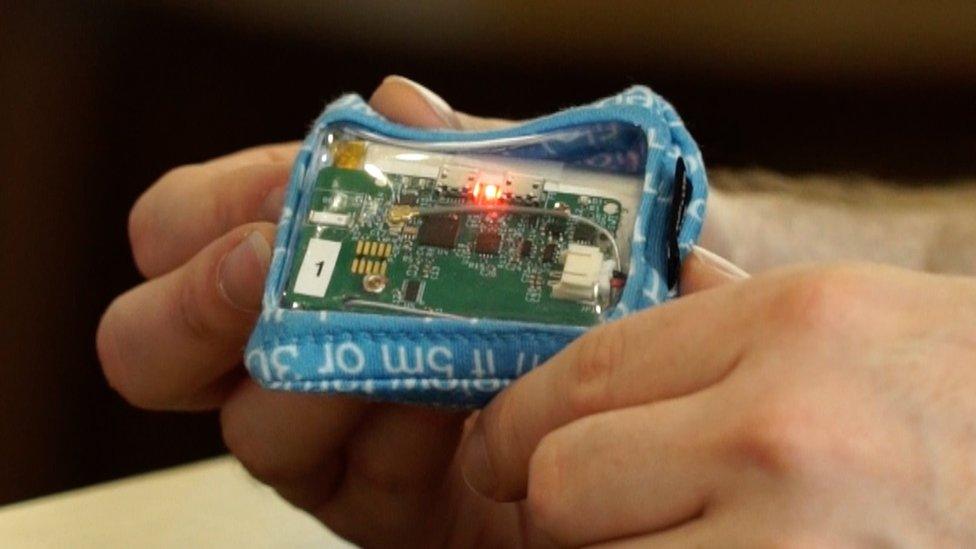

When I did, she was wearing a blue shirt covered in white letters, numbers and symbols - the code she used to create her device.

As a type one diabetic, Ms Lewis has to administer insulin whenever her blood sugar levels demand it. To make that easier, she has made her own pancreas.

"It's a small computer with a radio," she explained, holding the credit card-sized device in her hand.

"[It] reads data from my insulin pump. My glucose monitor does the math for me, and actually sends a command back to the insulin pump, to automate my insulin delivery."

Dana Lewis' artificial pancreas uses a radio transmitter to communicate with her insulin pump

Ms Lewis is perhaps the best advert for the the good side of the bodyhacking community, a person who created a device when traditional medical channels failed her.

Unregulated

But Aaron Traywick's Ascendance Biomedical is a more controversial example.

Mr Traywick claims - and there is no independent proof of this whatsoever - that his drugs can cure HIV, Aids and herpes. He says he suffers from the latter.

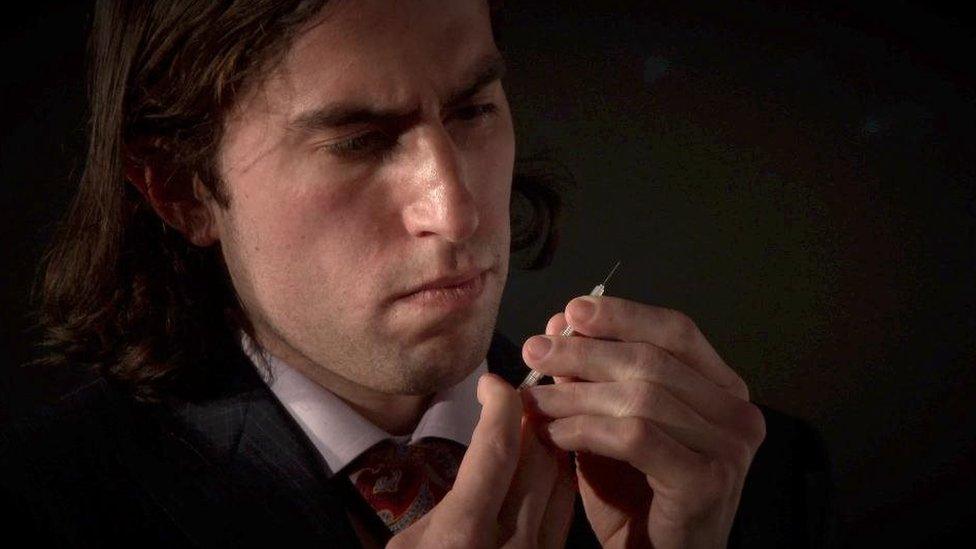

Indeed, at the event he performed a stunt on stage whereby he injected his own product into his leg - or at least tried to. There was some confusion about what exactly had transpired.

Mr Traywick skirts the law by self-medicating, and encourages others to do the same.

Officially he calls his product a "research compound", but in conversation often slips up and refers to it as "treatment" - a claim that could see him in choppy waters with the US Food and Drug Administration, the notoriously strict regulator.

The FDA calls companies like his "dangerous". But when asked by the BBC, it would not say whether it was monitoring Mr Traywick's activities.

In November, Ascendance Biomedical made headlines when a 28-year-old man injected himself with its HIV "research compound".

Mr Traywick told me he now plans to take that work to Venezuela.

"The best we can do, is we can say to these people 'we know you don't have access to this medication'," he says.

"They don't have any other options," he added, as if that was acceptable rationale for using an unregulated drug that was tested on only one person.

'Ridiculous'

At least one prominent bodyhacker has publicly taken issue with Mr Traywick's work.

US regulators have warned against companies like Aaron Traywick's Ascendance Biomedical

"The idea that any scientist, biohacker or not, has created a cure for a disease with no testing and no data is more ridiculous than believing jet fuel melts steel beams," wrote Josiah Zayner, a man who also works with so-called "do-it-yourself" drugs.

At the end of the weekend, I was left inspired by the efforts of Darpa, knowing what they could lead to for everyone - the agency has a great record of giving away its technology.

In hearing Dana's story, I was reminded that cheaper, smaller technology could continue to shake up the healthcare industry in an extremely positive way.

But sadly it's Mr Traywick's "work" that will stick with me.

Computer hackers have long held an anarchistic reputation for experimenting and breaking things - and, eventually, learning a thing or two that helps us all.

Standing on stage, trouserless but wearing a suit jacket and tie, Mr Traywick looked lost - and indifferent to the consequences of what he was doing.

- Published21 November 2017

- Published20 July 2017