Inside the highly charged scooter craze

- Published

- comments

WATCH: Will on-demand electric scooters be a hit?

Kyle Ramirez has surrendered his entire living room to electric scooters.

The 30-year-old tattooist’s apprentice spends his evenings collecting them from around the city of Oakland, California - one of more than a dozen across the US that have seen an invasion of the on-demand vehicles - before taking them back to his house to be put on charge.

For each one he fetches and returns early the next day, Kyle gets around $10. He typically manages to stuff eight of them into his Volkswagen Golf before heading back. Sometimes he’ll do a second run before the night’s out. He’ll do this seven days a week.

“Do you feel like you’ve given up a room of your house?” I ask, surrounded by the haul we collected together that night.

“I mean, a little bit!” he laughs, as he places T-shirts over each of the handlebars. The bright light on each of the scooters stays on while charging, and Kyle doesn’t want to disrupt his bearded dragon, external in the corner trying to get some sleep.

I ask if he worries about the electricity bill.

Kyle's house is quickly overrun by scooters once the night's collection has taken place

“So far it’s been alright. We haven’t really noticed the difference.”

Instant hit

Kyle is a vital part of an industry that is roaring into life thanks to more than $1bn in investment from the likes of Google and Uber.

At $1 to unlock and 15 cents per minute to ride, on-demand electric scooters have become an instant hit.

Ambitions to bring the GPS-tracked vehicles to Europe and Asia are well underway, propelled by a feeling that scooters offer a fun, cheap alternative to short car journeys.

Like car ride-sharing, scooters are being seen as a big force for disruption. Though unlike Uber, which put many cabbies out of a job, the disruption with scooters comes in a different form: space. It feels like they’re everywhere.

With no fixed docking stations, the scooters can also be found blocking doorways, strewn across streets, and even thrown into lakes.

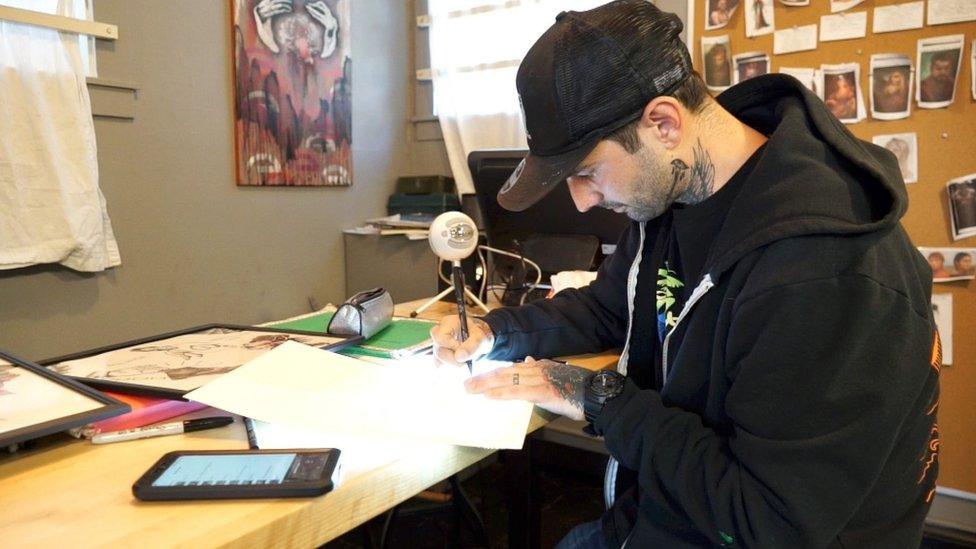

Kyle is a tattooist's apprentice - but the job does not yet pay

To some, scooters are just the latest craze from arrogant tech firms looking to make money without any regard for the community around them. When the scooters exploded onto San Francisco’s already messy streets earlier this year, residents’ meetings were hastily arranged.

“It would be very nice if the tech bros could come in and ask in a collaborative fashion for permission rather than after-the-fact forgiveness,” remarked San Francisco’s supervisor, Aaron Peskin.

One woman at a separate event, quoted by Wired magazine, external, joked: “I think that these scooters run amok are actually a plot of the young people to kill off all us old farts so they can have our rent-controlled apartments.”

Ordered off

Kyle picks up for Lime, one of two companies operating in Oakland. The other is Bird.

Both firms were in San Francisco too, but while Oakland is bustling with scooters, the city over the Bay has for now demanded they be removed.

Calling the shots is Tom Maguire from San Francisco’s Municipal Transportation Agency. He’s in charge of a permitting process that has seen 12 different companies put forward their best pitch as to why they should be granted one of five permits to operate.

Those given a permit will need to pay a $25,000 annual fee - and share something that’s arguably more valuable.

“We want them to show their accountability by committing to sharing data with us,” explains Mr Maguire.

“We want to know where the scooters are at all times.

“If their vehicles are tipped over, if their vehicles are blocking sidewalks, we expect them to clear that up.”

He also demands the firms make sure riders are riding safely - and that means with a helmet. He’s leaving it up to the firms to figure out how exactly to do that.

“We’re dealing with some of the most sophisticated tech companies in the world,” he says.

“So we’re challenging them.”

Any day now, a six-month trial will start, with 1,250 scooters allowed on the streets at first. All goes well, more will follow.

Beyond the US, the scooters can already be found in Berlin, Bremen, Frankfurt, Zurich and Paris. But London has been less welcoming - its transport authority has determined that the scooters are "powered transporters", and as such are only allowed on private property.

Crack of dawn

One of the requirements of the permits is that the scooters are taken off the streets at night before being returned in the morning - which is why I find myself back at Kyle’s house at 5:00am.

An app tells us where to go to put the scooters in the right place. When we drop them off, that’s when Kyle makes his money.

Kyle fits as many scooters as possible into his small car

As well as contractors such as Kyle - who can work as little or as often as they please - the scooter firms are busy hiring full-time workers to also do the job. On the day we filmed, Kyle himself was offered a permanent position - but he tells me he’s not sure he could do this all day, every day.

So for now he’ll remain a part of the newest incarnation of the “gig economy”, where hard-working people grind, almost invisibly, to make “tech innovation” a reality.

It strikes me as a decent earner, but one with little stability. Kyle’s pocket is at the mercy of the companies - who often change the rules about when and where scooters are picked up - and also by cities who can, at any moment, pull the plug.

________

Follow Dave Lee on Twitter @DaveLeeBBC, external

Do you have more information about this or any other technology story? You can reach Dave directly and securely through encrypted messaging app Signal on: +1 (628) 400-7370

- Published9 July 2018

- Published31 May 2018