Facebook bans pages aimed at US election interference

- Published

Facebook says it has removed 32 accounts and pages believed to have been set up to influence the mid-term US elections in November.

It said it was in the "very early" stages of the investigation and did not yet know who was behind the pages., external

It said the creators had gone to greater lengths to hide their identities than a Russia-based campaign to disrupt the 2016 presidential vote.

It described attempts to erase election interference as an "arms race."

What did Facebook discover?

The social network said in a blog that it had identified 17 suspect profiles on Facebook and seven Instagram accounts.

It said that there were more than 9,500 Facebook posts created by the accounts and one piece of content on Instagram.

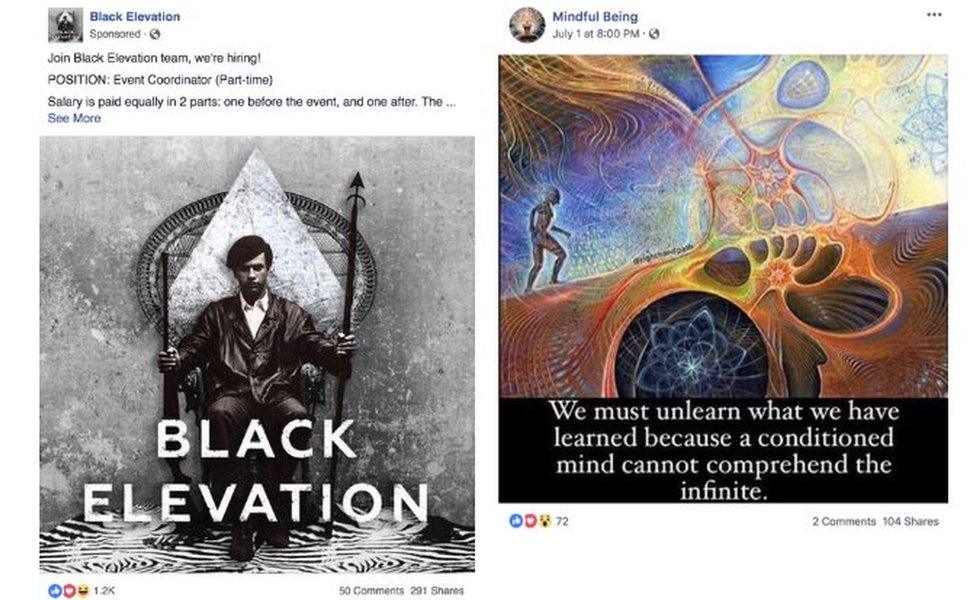

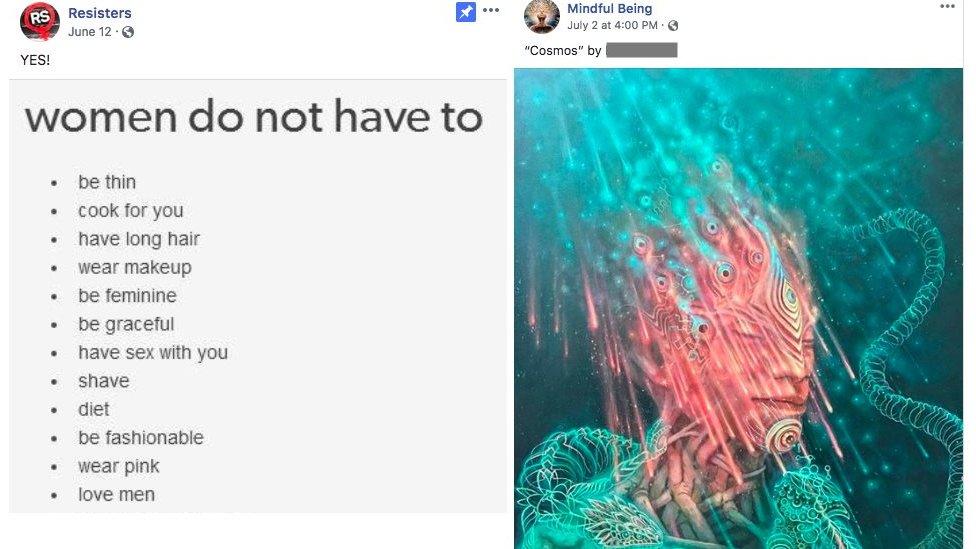

Facebook has shared some of the images posted by the accounts

In total more than 290,000 accounts followed at least one of the pages involved, it added.

Facebook said the suspect accounts had also run about 150 ads on Facebook and Instagram, costing a total of $11,000 (£8,300).

The most popular fake accounts were:

Aztlan Warriors

Black Elevation

Mindful Being

Resisters

Why can't Facebook be sure who is responsible?

The "bad actors" went to far greater lengths to cover their tracks than the Russian-based Internet Research Agency (IRA) had in the past, Facebook said.

This included using virtual private networks (VPNs) to hide their location, and using third parties to run ads on their behalf.

Furthermore, the social network said it had not found evidence of Russian IP (internet protocol) addresses.

But it did find one link between the IRA and the new accounts. One of disabled IRA accounts shared a Facebook event hosted by the Resisters page. The page also briefly listed an IRA account as one of its administrators.

Many of the posts included anti-Trump messages

It added that it "may never be able to identify the source" for the fake accounts.

"The set of actors we see now might be the IRA with improved capabilities, or it could be a separate group," explained Facebook's chief security officer Alex Stamos.

"This is one of the fundamental limitations of attribution: offensive organisations improve their techniques once they have been uncovered, and it is wishful thinking to believe that we will always be able to identify persistent actors with high confidence."

What is the company doing about it?

Facebook has removed the suspect accounts, but says other legitimate page administrators unwittingly interacted with them.

For example, after the Resisters account created a Facebook event for a protest on 10 to 12 August called "No Unite the Right 2", five other page owners offered to co-host the demonstration and posted details about transportation and locations.

Facebook said it had contacted the admins involved and would alert the 2,600 users who had expressed interest in the event.

Some of the flagged posts would have been difficult for the public to identify as election interference

The firm said it would also continue efforts to detect further misuses of its platform and work more closely with law enforcement and other tech firms to understand the threats faced.

How have US politicians reacted?

Democratic congressman Adam Schiff said: "Today's announcement from Facebook demonstrates what we've long feared: that malicious foreign actors bearing the hallmarks of previously-identified Russian influence campaigns continue to abuse and weaponise social media platforms to influence the US electorate."

Democratic Senator Mark Warner, who is vice-chairman of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, also pointed his finger at Moscow.

"Today's disclosure is further evidence that the Kremlin continues to exploit platforms like Facebook to sow division and spread disinformation, and I am glad that Facebook is taking some steps to pinpoint and address this activity," he said.

Republican Senator Lindsey Graham added that he intended to pursue retaliatory measures by introducing a sanctions bill against Russia on Thursday "that has everything but the kitchen sink in it".

"It'll be the sanctions bill from hell. And any other country that is trying to interfere with our election should suffer the same fate."

Senate Intelligence Committee chairman Richard Burr, a Republican, said that the operation's apparent goal had been to "sow discord, distrust, and division in an attempt to undermine public faith in our institutions and our political system".

"Russians want a weak America," he added.

Analysis: Dave Lee, North America technology reporter

This may look like another disastrous headline for Facebook, but it isn't.

Earlier in the year it promised to improve its so-far shambolic efforts at removing misinformation. It promised to hire more people, enlist outside help and work on new automated detection methods.

Today it was able to share a tangible, politician-friendly example of how those efforts came together, to quash a misinformation campaign before it apparently caused much harm.

But the future is troubling and predictable. This latest campaign was more sophisticated than anything that came before it - the use of third parties to buy advertising in the US is a difficult problem for Facebook to tackle without snarling up its ads operation.

And to state the obvious, while Facebook was able to detect this specific operation, none of us really know how big this problem is.

What happened with the 2016 elections?

Shortly after the vote, Facebook's chief Mark Zuckerberg derided suggestions that fake news posted to the platform had influenced the presidential election, saying it was a "pretty crazy idea".

But he has since apologised for being so dismissive.

In September 2017, Facebook acknowledged that Russians had indeed used fake identities to try to influence the US electorate before and after the election, and had posted comments, ads and details about street protests to achieve this.

US intelligence agencies have also concluded that Russian state operators used fake social media accounts in an attempt to interfere with the campaign.

President Putin has, however, denied that Russia meddled.

- Published29 July 2018

- Published11 April 2018