Facebook and Twitter 'too slow' to tackle meddling

- Published

Jack Dorsey and Sheryl Sandberg appeared at the hearing in Washington DC

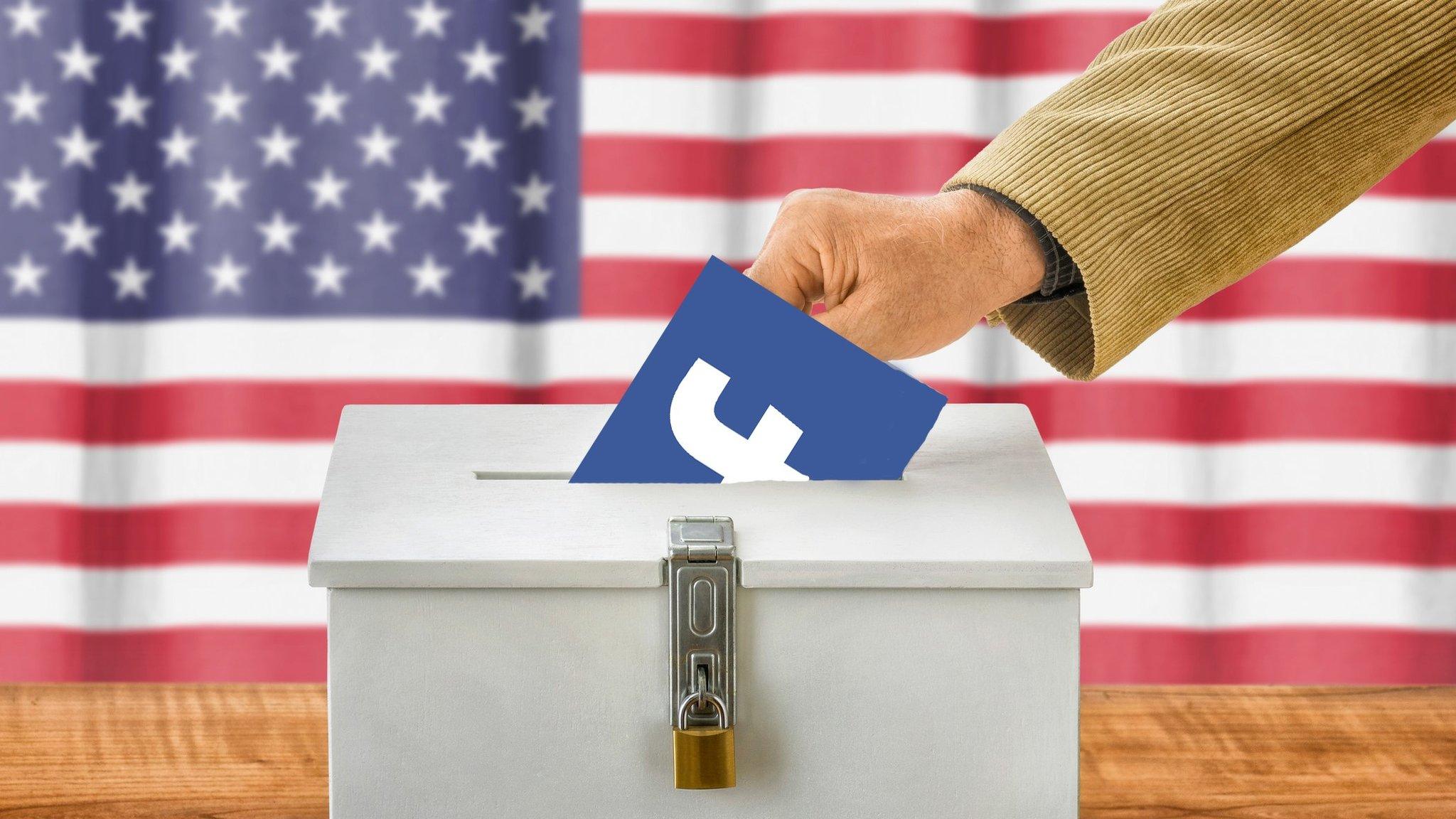

Facebook and Twitter have said that they took too long to tackle foreign campaigns to meddle in US elections.

Responding to lawmakers, Facebook's chief operating officer Sheryl Sandberg said the social network was "too slow" to act on election interference.

Twitter's chief executive Jack Dorsey said his platform was "unprepared and ill-equipped" for the "weaponisation" of debate.

Google did not show up to the Senate Intelligence Committee hearing.

Opening the hearing, Democratic senator Mark Warner said he was "deeply disappointed" that Google "chose not to send its own top corporate leadership".

An empty chair was left for Google

What was the hearing about?

The senate committee focused on what the technology giants were doing to prevent future election meddling.

It followed claims that Russia and other foreign actors spread misinformation and propaganda ahead of the 2016 presidential election.

"With the benefit of hindsight, it is obvious that serious mistakes were made by both Facebook and Twitter. You, like the US government, were caught flat-footed by the brazen attacks on our election. Even after the election, you were reluctant to admit there was a problem," said Mr Warner.

He warned that the social networks could face new regulations.

"The era of the wild west in social media is coming to an end. Where we go from here is an open question," he told the hearing.

Analysis

by Dave Lee, BBC North America technology reporter at the Capitol Building

The empty chair left for Google is what those in the public relations business refer to as "terrible optics". In other words, it really didn't look good.

Google was accused of not taking the issue seriously enough to bother to send a senior executive - though I suspect Google's gamble was more about avoiding the inevitable questions about its plans in China.

Of the companies that did turn up, this hearing felt like what we'd seen before. Senators' questions - while marginally more informed than in previous hearings - failed to land any serious punches. The companies now know the cheat codes that get them through these hearings: admit mistakes, pledge to do better, offer to work on regulation.

But I felt the self-described "shy" Jack Dorsey offered something a little more profound, when he drifted into talking about the incentives social media provides: incentives that make us obsess about our follower count and level of engagement, arguably more than we care about the quality of what we share in the "public square".

Mr Dorsey seems willing to look inward and rethink how his business works at its most basic level. I'm looking forward to seeing how that approach plays out.

Facebook, on the other hand, is reaching out for help. It can't solve this problem alone, Ms Sandberg said. It needs government, law enforcement and security specialists to work on this issue. She's right, but Facebook will need to be more open about how it works in order for those kind of collaborations to be truly successful.

What did the senators ask?

Mr Warner asked whether Twitter would introduce an indicator to show which accounts were humans and which were automated bots. Mr Dorsey said Twitter had been "considering" the idea, and could label accounts as bots as long as it could detect them

Mr Heinrich asked whether a US citizen "intentionally spreading false information" would violate Facebook's community standards. He gave the example of somebody claiming the victims of a mass shooting were actors. Ms Sandberg said Facebook did not want to be the "arbiter of truth" and worked with third-party fact-checkers to identify misinformation. Stories flagged as false had their distribution "massively decreased", she said

Ms Sandberg and Mr Dorsey are giving evidence under oath

Ms Collins asked whether the social networks would notify people if they had been engaging with fake accounts, once those accounts were identified and removed. Mr Dorsey said Twitter had not done enough. Ms Sandberg said Facebook had notified people in specific cases - including people who had indicated they would attend a fake event set up in Washington

Ms Collins asked why Twitter did not notify politicians that were the subject of misinformation campaigns by foreign agents. "I agree, it's unacceptable," said Mr Dorsey

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Mr King asked whether Facebook could help people judge the validity of sources in the same way that auction site eBay gives sellers ratings based on feedback. Ms Sandberg said people could decide for themselves which people and news sources to follow, and that it was easy to unfollow sources they did not trust

Mr Manchin asked whether new laws should be introduced to hold social networks responsible for illegal drugs sold on the platforms. Facebook and Twitter both said selling drugs was against their terms of service and that they took action when they discovered such activity

Facebook chief operating officer Sheryl Sandberg

Ahead of the hearing, Facebook submitted written testimony outlining how it had disabled 1.27 billion fake accounts globally between October 2017 to March 2018. It said it employed 20,000 people to work on safety and security.

In July, the social network announced that it had removed 32 accounts and pages believed to have been set up to influence the mid-term US elections in November.

A month later it said that it had removed hundreds more "misleading" pages and accounts which targeted people in the Middle East, Latin America, the UK and the US.

Is Twitter censoring conservative voices?

Twitter chief executive Jack Dorsey

Twitter's Dorsey will also face questions from the House Committee on Energy and Commerce about perceived conservative censorship on its platform.

President Trump has repeatedly accused Google, Facebook and Twitter of political bias and threatened regulation of the platforms.

In written testimony submitted ahead of the hearing, external, Mr Dorsey denied that his firm de-emphasised certain accounts in search results, a practice known as "shadow banning".

"Twitter does not use political ideology to make any decisions, whether related to ranking content on our service or how we enforce our rules," he said.

"We do not shadow-ban anyone based on political ideology."

- Published5 September 2018

- Published5 September 2018

- Published31 July 2018