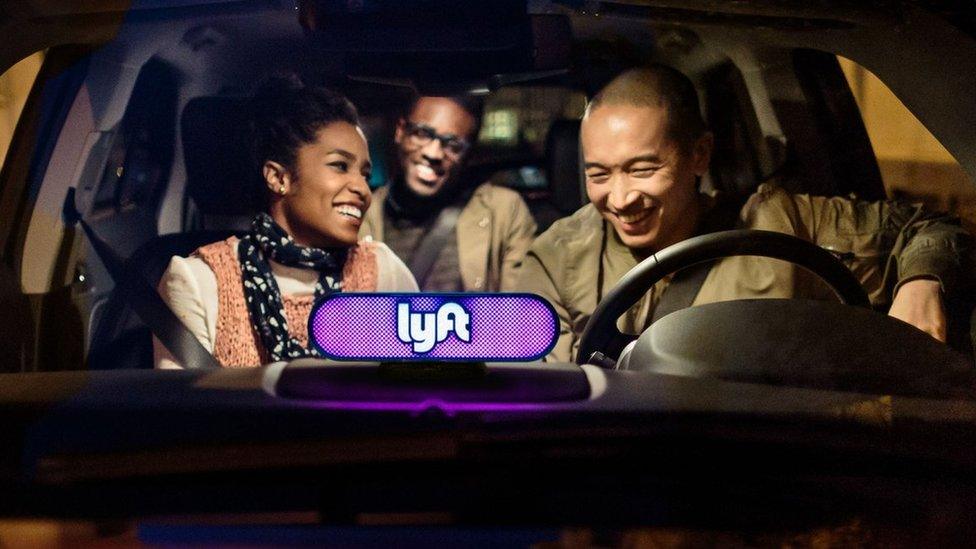

'Thrown to the wolves' - the women who drive for Uber and Lyft

- Published

Chrystle Barajas, a 44-year-old single mother, said she had tried to hide her fear as her passenger had described his fantasy of having sex with a single mother.

"He made several unwanted advances," Ms Barajas told BBC News. The ride came to an end soon after.

"When I dropped him off, he told me that if I go to the right, it takes me out to the main street," she said.

But it wasn't the way out - it was a cul-de-sac.

"As I came back around, he was standing there with his pants down... holding himself," Ms Barajas said.

"I'm very thankful he was not in my car when he did this but I was still traumatised."

Ms Barajas got in touch with Uber immediately. A company representative said it would investigate - but Ms Barajas said she had never been told the result of that investigation and had been left wondering whether the man was free to book other Uber rides, with other women, in future.

"They told me they could not tell me the outcome due to privacy issues," she told BBC News.

Uber confirmed to BBC News the man's access had been temporarily deactivated while it had investigated.

It would not confirm the outcome of that investigation but a spokesman stressed it took into consideration both accounts of every incident, as well as a rider's prior history.

'Grabbed'

The BBC interviewed dozens of female drivers who work for Uber and Lyft, the two biggest ride-share companies in the US.

All expressed concern that, as women, they regularly felt at risk and did not always feel the companies prioritised their interests.

"I had to report a passenger who grabbed me while I was driving," said Zuwena Belt, a Lyft driver in Portland, Oregon. Ms Belt runs a Facebook group, external for female ride-share drivers.

"After ending the ride, I placed a call to Lyft's critical response team and the police. While [Lyft] were on the line, they refused to share information with the officer on scene."

Lyft said it worked closely with law enforcement and had a process for providing passenger information but in almost all cases a warrant was required.

Another driver, in Arizona, described how her passenger "pulled his pants snug against his erect penis and asked me what I thought about it".

"I replied that I thought it was inappropriate," she said.

She gave the rider a one-star rating, a step that should have prevented the app from pairing her with the man from then on. But after "maybe 10 minutes had passed, Lyft matched me with him again".

Lyft told BBC News it had now deactivated the passenger but did not offer an explanation as to why the driver had been matched with him twice.

'I just wanted your number'

Several drivers told BBC News how both Uber and Lyft's "lost and found" function - where passengers can get in touch directly with drivers to recover things left in the car - were being abused by those seeking to have more contact with drivers well after a trip had ended.

While discussion over lost items is meant to occur within the app, with obscured contact details, there are some scenarios that prompt the companies to request drivers to get in touch with passengers directly, or vice versa.

Though drivers could hide their number, none of the women spoken to said the companies had advised them to do this, or showed them how.

One Uber driver in South Carolina told how she had been asked to contact a passenger about a lost item, only to get a text message back saying: "Hey Jane [the name has been changed] I didn't really lose anything in your car - I just wanted your number."

"Attached was a... video [of his penis]," the woman added.

Other drivers described how people would use the number obtained from the driver to look them up on various websites, such as Facebook.

"I rejected a guy on Facebook and he gave me a low rating," said Mary Thompson, from North Carolina.

"After a similar scenario happened three times, I just deactivated my account."

Uber and Lyft said abuses of this system could - and did - lead to passengers being banned from the service.

Unwanted guests

Sometimes, the unwanted contact after a ride can go further.

Wendy Gonzalez, who lives near Los Angeles, showed BBC News footage from her home security camera, recorded in September 2018.

It showed two men turning up at her door to retrieve a phone they believed they had left in the back of Ms Gonzalez's car the previous night.

"The door's not even locked," said one of the men, after several minutes of knocking and peering through a window. "Hello hello? Good morning? Anybody home?"

It is unclear how the men found out where Ms Gonzalez lived.

An Uber support agent told her it had probably been through a third-party tracking app, perhaps Apple's Find My iPhone. But Ms Gonzalez's car was not parked directly outside of her house.

In the video, when Ms Gonzalez appears at the door, the man looks startled and says: "My phone is actually still inside your vehicle and I was hoping to get that back now."

Ms Gonzalez said at one point one of the men had stepped into the house but the video's angle did not capture that.

She complained to Uber and was told the account holder would be "reminded of the community guidelines".

"We evaluate all complaints and safety concerns thoroughly and remove users from the system when we see clear evidence and patterns of unsafe behaviour," an Uber safety rep wrote later.

"However in accordance with our privacy policy, we can't share the specific results of our evaluation process."

"I didn't drive much after that," Ms Gonzalez added. Uber said the rider had received a warning.

'You're in the range, baby'

Neither Uber nor Lyft know how much of an impact this is having on their business.

Uber said it didn't collect data on how many women joined (or left) its platform, though an external study, external published in 2017 suggested about 27% of its drivers were female.

Lyft said its workforce was about 29% female, based on internal figures.

Researchers have, however, suggested that female drivers earned less per hour than their male counterparts because they are more cautious about picking up people in areas with higher crime rates and more drinking establishments.

Minneapolis driver Ann Marie Lund shared one experience of driving four men who spent the ride commenting on her looks.

Her dash cam footage captured a ride in December that lasted about six minutes, beginning with Ms Lund being told she was a "ranger".

"Ranger status is that you're in the range of being a hot girl," the man in the front seat explained.

"Three to a seven," remarked a voice from behind her. "So you're in the range, baby."

Ms Lund can be seen smiling and engaging. She called it "survival mode". Other women had their own names for the same goal: a way of shutting down inappropriate conversation without seeming impolite or "uptight".

"It's not worth my rating suffering from retaliation," said one driver, who did not want to be named.

"The driver will lose perks and will eventually be deactivated if their rating is too low."

Sometimes, though, "survival mode" isn't enough.

Jacqueline Stewart, who drives in Tuscon, Arizona, said: "I had a passenger give me a three-star rating after he claimed that I wasn't as pretty as my profile picture. It dropped my rating from a 4.93 to a 4.89."

No defence

The view of many women interviewed was that most harassment was inevitable when working in ride-share, in a way society arguably wouldn't accept in any other kind of workplace.

Uber and Lyft said safety was a top priority, though as of yet the companies do not share data with each other about customers who have been banned for serious offences.

Some of the incidents were not reported by the drivers, who often said they were worried about making a fuss in case they were deactivated by the platforms.

In particular, some women were reluctant to talk about how they had protected themselves, because of Uber and Lyft's policies on defensive weapons.

"Neither one of them allow you to carry any type of weapon," said Shelly - not her real name - who caught a passenger masturbating in her car.

After she reported the incident and wrote about her experience online, it was discovered the same passenger had done the same thing in another woman's car as well.

He was arrested and is currently awaiting trial.

"I don't think that's right," Shelly said of the weapons policy. "If we're female, we should at least be allowed to carry pepper spray."

In response, Lyft said its no weapons policy was designed to make drivers and riders comfortable.

Uber's view is more nuanced. It does allow pepper spray, but prohibits using it in a threatening way.

For guns, the company has a firearms policy that bans "carrying firearms of any kind while using the app" - but a spokesman said local state laws can override parts of that policy.

Deterrent

In private Facebook groups, women offer advice for each other on handling the regular occurrence of inappropriate behaviour at both ends of the scale.

For some, dashcams to record passengers have been a good deterrent. Others said they actively dressed down and didn't wear any make-up. Some said they wore fake wedding rings.

Jeanette Davis, a driver in Sacramento, who said she had been stalked for a short period online by a passenger who had found her on Facebook, said the first step would be to have better advice given to women before they began driving.

"I got approved for Uber within 45 minutes of sending my application in," she said.

"I could have gone online that same night. We are thrown to the wolves."

Illustrations by Emma Russell

- Published16 July 2018

- Published26 June 2018

- Published6 December 2018