What is Article 13? The EU's copyright directive explained

- Published

The final version of a controversial new EU copyright law has been agreed after three days of talks in France.

Google has been particularly vocal about the proposed law, which it says could "change the web as we know it".

Article 13 of the EU Copyright Directive states services such as YouTube could be held responsible if their users upload copyright-protected movies and music.

In a few weeks, MEPs will vote to decide whether it becomes law.

The EU last introduced new copyright laws in 2001. The EU says it wants to make "copyright rules fit for the digital era", but not everyone agrees with the proposed changes.

If the UK leaves the EU with a deal, and the directive becomes law, it would apply to the UK during any transition period.

What is Article 13?

Article 13 is the part of the new EU Copyright Directive, external that covers how "online content sharing services" should deal with copyright-protected content, such as television programmes and movies.

It refers to services that primarily exist to give the public access to "protected works or other protected subject-matter uploaded by its users", so it is likely to cover services such as YouTube, Dailymotion and Soundcloud.

However, there is also a long list of exemptions, including:

non-profit online encyclopaedias

open source software development platforms

cloud storage services

online marketplaces

communication services

What does Article 13 say?

Article 13 says content-sharing services must license copyright-protected material from the rights holders.

If that is not possible and material is posted on the service, the company may be held liable unless it can demonstrate:

it made "best efforts" to get permission from the copyright holder

it made "best efforts" to ensure that material specified by rights holders was not made available

it acted quickly to remove any infringing material of which it was made aware

These rules apply to services that have been available in the EU for more than three years, or have an annual turnover of more than €10m (£8.8m, $11.2m).

Article 13 says it shall "in no way affect legitimate uses" and people will be allowed to use bits of copyright-protected material for the purpose of criticism, review, parody and pastiche.

What are the concerns?

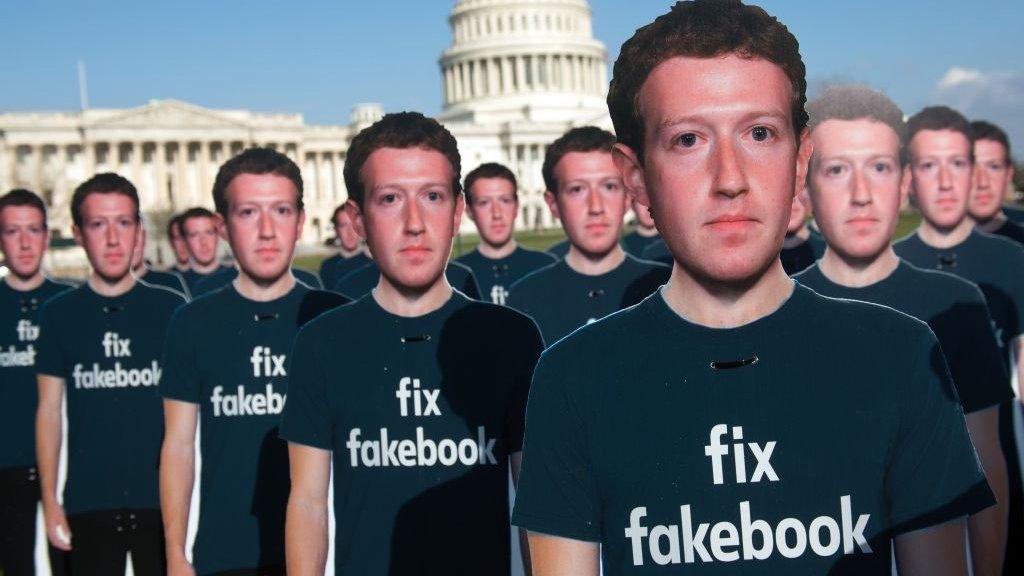

YouTube is a vocal critic of Article 13

Critics say it would be impossible to pre-emptively license material in case users upload it.

German MEP Julia Reda suggested services would have to "buy licences for anything that users may possibly upload", external and called it an "impossible feat".

Article 13 does not force companies to filter what users are uploading, although critics say companies will be left with no choice.

YouTube already has its Content ID system, which can detect copyright-protected music and videos and block them. But critics say developing and implementing this type of filter would be too expensive for small companies or start-ups.

Others have warned that algorithms often make mistakes, and might take down legitimately used content.

"Filters will subject all communications of every European to interception and arbitrary censorship if a black-box algorithm decides their text, pictures, sounds or videos are a match for a known copyrighted work," said a blog by online rights group EFF., external

Article 13 does say services must put in place a "complaint and redress mechanism" so that their users can quickly resolve disputes if their content is blocked by mistake.

Many in the entertainment industry support Article 13, as it will hold websites accountable if they fail to license material or take it down.

What was YouTube campaigning for?

Before the final text of the directive was agreed, there were three versions: one by the European Parliament, one by the Council of the EU, and one by the European Commission. They worked together to produce the final version of the text.

YouTube had warned that the European Parliament's original draft was its worst-case scenario.

It dramatically claimed it would have to block existing videos and new uploads from creators in the EU, and encouraged prominent vloggers to make videos about Article 13.

It warned its Content ID system only worked if rights-holders engaged with it and "provided clarity" about what material belonged to them. It said it would be "too risky" to let anybody in the EU upload anything at all.

The final version of Article 13 says services must make "best efforts" to remove copyright-protected videos in cases where "the rights holders have provided... the relevant and necessary information".

That seems like a win for YouTube.

In a statement, Google said: "We'll be studying the final text of the EU copyright directive and it will take some time to determine next steps. The details will matter, so we welcome the chance to continue conversations across Europe."

Will Article 13 affect video game streamers?

Video gamers who share their gameplay on video-streaming services such as Twitch and YouTube highlight the complexity of copyright online.

"Multiple copyrights can exist in a single product," explained lawyer Kathy Berry, from Linklaters. "Video game studios own various copyrights in their games: the underlying code, the graphics, music, dialogue.

"When a gamer creates a video game video for YouTube, the video itself is a new copyright work owned by the gamer. However, as it also incorporates copyright works owned by the video game studios, the authorisation of both the gamer and the studio would be required to put it online."

Currently, most video game publishers let gamers share videos of their gameplay online. Nintendo had been more restrictive, but recently relaxed its rules.

In theory, if Article 13 became law, games studios could tell Twitch and YouTube not to show videos of its games.

"Studios tend not to enforce their rights against YouTube gamers in order to avoid the PR implications of being heavy-handed with fans, and because the videos can have significant promotional value," said Ms Berry.

Gamers may be able to argue that their videos are exempt from Article 13 because they have added their own commentary, criticism or review. But Ms Berry warned: "These defences have been largely untested in the courts in this context".

What happens next?

Ms Berry said Article 13 still contained some "broad and ambiguous terms", such as the requirement for services to demonstrate "high industry standards of professional diligence".

She said it would be "likely to result in an ongoing lack of legal and commercial certainty" until legal cases set a precedent and "flesh out" the directive.

The proposed law will face a final vote in the European Parliament in the next few weeks. If it passes, it will be implemented by national governments over the next two years.

- Published12 February 2020

- Published12 September 2018

- Published8 June 2018