Tech Tent: Talking to Mr Raspberry Pi

- Published

The Lovie awards honour European computer industry pioneers

It was a scheme with limited ambitions - getting more young people with coding skills to apply for a university course.

But seven years after its launch, Raspberry Pi has become one of the most successful computers in history. On this week's Tech Tent, we talk to the project's founder about where it came from and what is next.

Stream or download, external the latest Tech Tent podcast

Listen live every Friday at 14:00 GMT on the BBC World Service

Small start

This week, Pi creator Eben Upton was honoured with the Lovie Award for lifetime achievement, recognition of the extraordinary impact that the Raspberry Pi has had.

It was conceived as a charitable venture at a time when Eben Upton was interviewing applicants for the computer science course at Cambridge University and was disappointed at the number and calibre of the young people he was seeing.

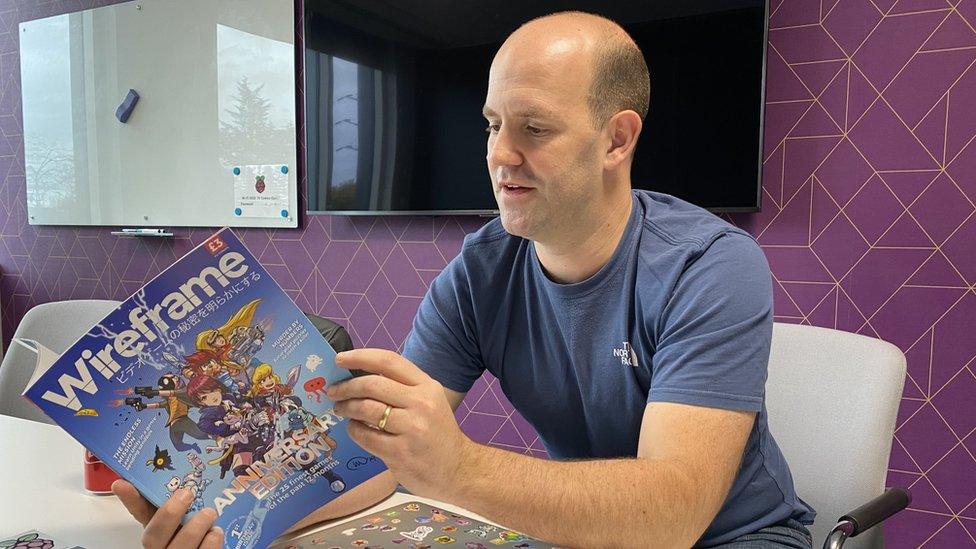

When I met him this week at Raspberry Pi's commercial headquarters in Cambridge - which is churning out substantial amounts of revenue for the charitable arm - he told me that as far as the original aim was concerned, it was job done.

From a low of 200 applicants to study computing, they were now up to 1,100.

"We have twice as many people applying to study computer science at Cambridge as we had at the height of the dotcom boom. And I understand from people that are still involved in the admissions process, that when you ask them how did you get into computers, they do say 'Raspberry Pi.'"

But what was unexpected - and drove the project off course for a while - was the huge enthusiasm not from children but from 40-something hobbyists who saw in the Raspberry Pi the rebirth of computers like the BBC Micro which they had cut their teeth on in the 1980s.

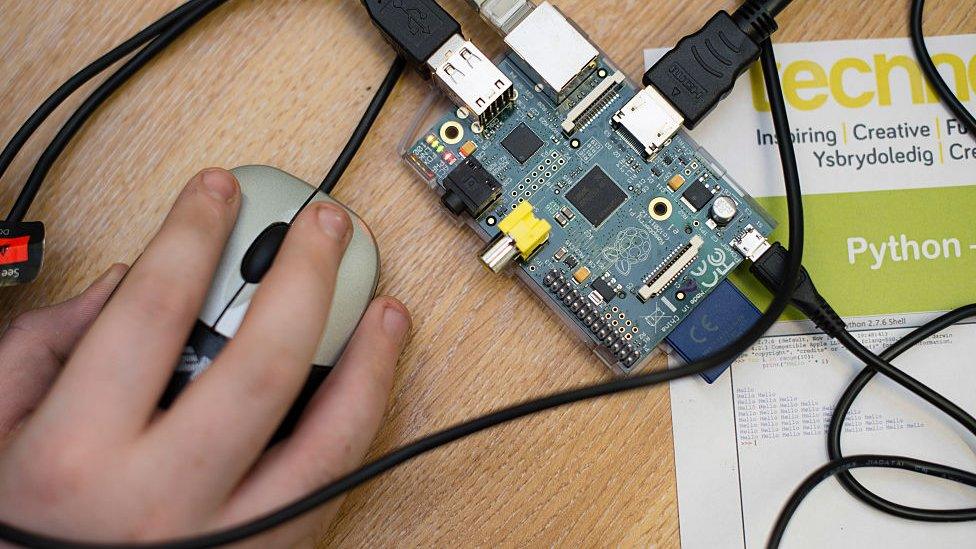

The Pi has helped get a lot of schoolchildren interested in computers

Mr Upton says, however, that these enthusiasts ended up being the people who took the Raspberry Pi into schools: "All those people were increasingly volunteers in after-school clubs. So that enthusiasm in the hobbyist community was then feeding back into the informal bit of education."

At the same time manufacturers were finding a place for the tiny computer in all sorts of industrial processes, and sales continued to soar. Nearly 30 million have been sold, making the Raspberry Pi the third most successful computing platform after the PC and the Mac.

So where next? Around 70 staff work on the commercial side, compared with 130 on the charity arm whose mission continues to be computing education. One commercial project - publishing a clutch of magazines including one about games development - seems surprisingly analogue, though Upton says it all fits in with the Pi's educational mission.

As he shepherds me round the offices on a Cambridge science park, we whizz past a research lab where a secret project that he won't tell me about is under way - but it is clear that this still tiny business has big ambitions.

Raspberry Pi is the tech start-up success that happened by accident - so at a time when home-grown firms across the UK and Europe lack confidence, what can they learn from it?

"I think if you try and build a business which stays focused on doing one thing, and doing it well, and you plug away at it year after year after year, you can build something that grows."

But he says the key is to think beyond borders: "It's really important to us to have that kind of global ambition. I think we've got the talent here in the UK to make a go of it."

After my visit to Raspberry Pi, I went on to see two other Cambridge companies. One, CMR Surgical, was a medical robotics firm already valued at over $1bn (£780m) five years after it was founded. The other was a tiny start-up called Intellegens founded by a physics tutor at a Cambridge college, and developing machine learning techniques to discover new materials.

In this university city, there are still plenty of people hoping to turn Cambridge ingenuity into world-class businesses.

Stream or download, external the latest Tech Tent podcast

Listen live every Friday at 14:00 GMT on the BBC World Service

- Published5 September 2019

- Published24 June 2019

- Published8 May 2019